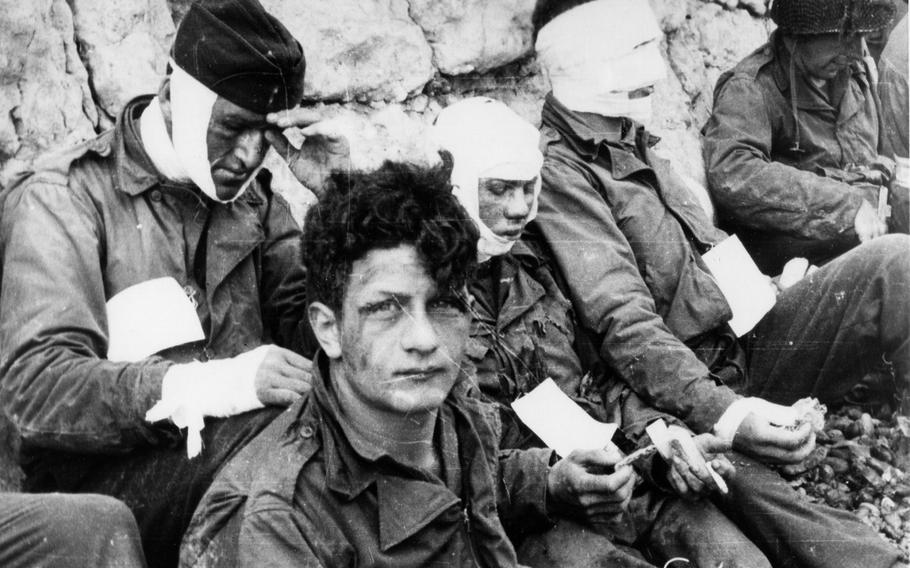

Wounded men of the 3rd Battalion, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, receive cigarettes and food after they had stormed Omaha beach on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Photograph from the Army Signal Corps Collection in the U.S. National Archives. (U.S. Army Signal Corps)

Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower had his resignation letter ready for a reason: the success of Operation Overlord was never a given.

When the Allies stormed the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944, they faced daunting odds as they attacked the Nazis’ “Atlantic Wall.”

“If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone,” Eisenhower wrote in a statement to be read to the American people in the event of failure.

The statement proved unnecessary — the largest amphibious assault in military history was a success, though 4,414 allied troops were killed that day. But given the slim margins for victory, it begs the question: What if D-Day had failed?

A common conclusion among armchair generals is that Germany would have gone on to win the war, but that might have been an unlikely scenario.

“By that point in the war, the Russians are barreling toward Germany,” said Kurt Piehler, director of Florida State University’s Institute on World War II and the Human Experience. “The outcome if D-Day failed is the Soviets would have liberated France, which would have had a very different postwar map.”

Around the time of D-Day, the tide had begun to turn on the eastern front, where the Soviets had expelled the Germans from Russian territory at enormous cost after three years of fighting.

Just two weeks after D-Day, the Soviets launched Operation Bagration, a surprise attack involving 1.5 million Russian troops who blasted through the German army in Belarus. The operation was the beginning of what would be some of the largest losses for the German military during the war. The Russians would wipe out 28 of 34 German army divisions on the eastern front during the Bagration campaign.

By August, the Red Army was on the doorstep of Warsaw and Berlin wasn’t far off. At the same time, allies had made it to Paris. But if D-Day failed, it would have taken time for the U.S. to regroup for another invasion. It took years of planning to launch D-Day in the first place.

“Roosevelt really hated the Nazis, so I see him as persevering,” Piehler said.

It isn’t clear how the Germans would have reacted in the event of a D-Day victory. They might have moved forces east to deal with the Russians, but Hitler also would have been concerned about being attacked again in the West.

Nonetheless, by this point, the Russians had momentum. “The dirty secret is the Russians were going to win the war,” said Stephen Bourque, professor emeritus of military history at the School of Advanced Military Studies in Fort Leavenworth, Kan. “They (the Russians) are moving pretty quick at this point.”

If D-Day failed, “the Russians would have ended up in France,” Bourque said. “The Russians could have ended up in the Netherlands or Belgium. What would that have been like?”

It could be argued that D-Day, more than being a decisive factor in winning the war in Europe, ultimately saved western Europe from being dominated by the Soviet Union in the way other countries were under the Iron Curtain during the postwar period. While Britain declared war on Germany over its annexation of Poland, the U.S. and Britain essentially ceded the country to the Soviets who liberated it from the Nazis.

After Germany’s surrender, Europe was divided and countries like East Germany, Poland, Romania, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria served as satellite states of the Soviet Union.

Would the U.S. have ceded all of Germany and France — the bulk of Western Europe — to the Soviets if the Red Army had pushed through because of D-Day’s failure? If the U.S. demanded the Soviets pull back, would Joseph Stalin have complied or staked his claim? And if the Soviets held their position, would the Cold War have come to an immediate, violent head in 1945?

Historians say it’s impossible to guess how it all could have played out.

But by late summer of 1945, when President Harry S. Truman and Joseph Stalin met in Potsdam, Germany, to finalize the postwar map, the military balance of power had dramatically changed in the American’s favor.

Truman let his Russian counterpart know in Potsdam that the U.S. had developed a new secret weapon without offering details. Days before their meeting, the U.S. had successfully tested the atomic bomb.

If D-Day had failed, and the Soviets were deep into western Europe by war’s end, Truman could have used the threat of a nuclear attack to force Stalin back.

Truman would soon show a willingness to deploy his secret weapon.

During the Potsdam meetings, it was agreed that the Soviets would join the war against Japan, with an invasion date of Aug. 15. But Truman, perhaps leery about the Russians gaining a foothold in the Pacific and eager to send a message to Stalin about overreaching in Europe, ordered a nuclear strike shortly before the Soviets were to join the fight.

On Aug. 6, the U.S. dropped the first of two nuclear bombs on Japan, which brought an end to the war there and marked the start of the Cold War. Four years later, the Soviets had a nuclear bomb of their own.