()

This article was part of Stars and Stripes’ 2010 special five-day report “The Long Goodbye,” published as a five-day series Aug. 16-20, 2010, as U.S. combat troops exited Iraq. Stars and Stripes wrote about the series:

“As he launched the U.S. invasion of Iraq on March 19, 2003, President George W. Bush laid out America’s goals: ‘to disarm Iraq, to free its people, and to defend the world from grave danger.’ More than seven years later, whether the mission has finally been accomplished is far less clear. [In this series,] Stars and Stripes looks at the costs of the war through the eyes of Iraqis and Americans and asks: What difference did we really make?”

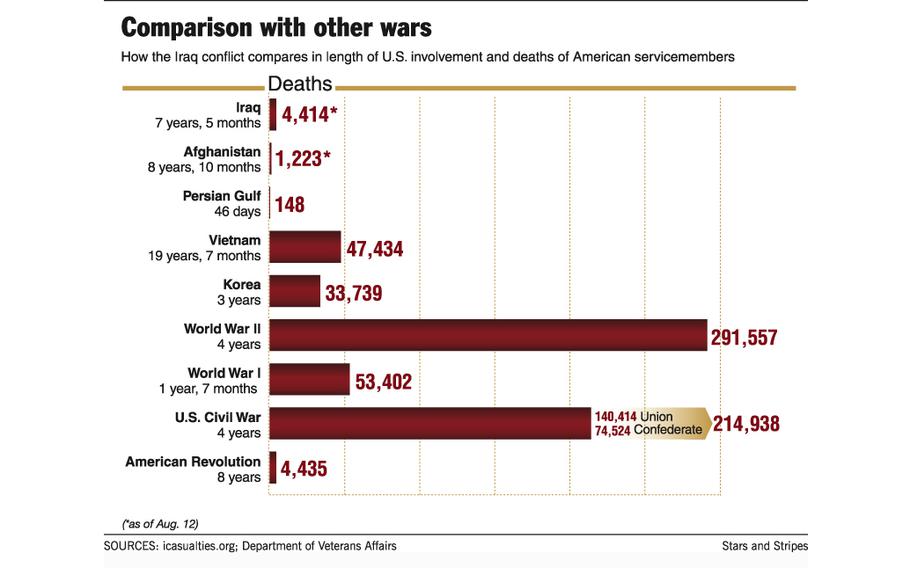

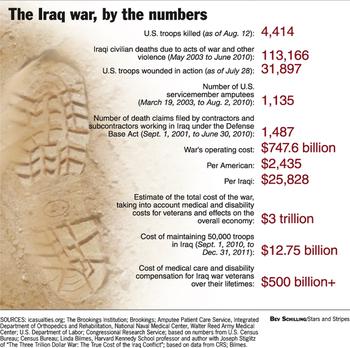

BAGHDAD — Seven years. $748 billion. 4,414 American servicemembers killed. And more than 113,000 Iraqi civilians dead.

The top line costs of America’s war in Iraq have been staggering.

But as the last U.S. combat troops finally extricate themselves from this ancient, embattled land by the end of this month, it’s the bottom line that Americans and Iraqis, politicians and pundits, the servicemembers who fought on the front lines and their families who sacrificed back home, are left to ponder:

After all the death and destruction — and rebirth and rebuilding — what difference did America really make in Iraq?

As in nearly every war throughout history, the Iraq war proved the law of unintended consequences.

The U.S. declared it was invading Iraq in March 2003 to stop the spread of Saddam Hussein’s supposed weapons of mass destruction — and instead the war fueled the proliferation of a frustrating and deadly class of terrorist weapons, the dreaded “improvised explosive devices,” or IEDs.

The Bush administration argued that the war was necessary to interdict Saddam’s support of al-Qaida — yet today, the war has become a rallying cry for the terrorist group from Pakistan and Afghanistan to Somalia and Yemen.

Iraq has held democratic elections — but the nation’s fractious political parties have been fighting to form a new government for five months. By the end of the month, the U.S. military presence in Iraq will drop to 50,000 noncombat troops, and a complete U.S. withdrawal is planned by the end of 2011.

But many key issues remain unresolved, sectarian schisms run deep and Baghdad’s streets are filled with more apprehension than relief. Serious doubts about the wisdom of the long war linger.

“I have a question for you: Before the Americans came to Iraq, was there any terrorism or sectarian fighting?” asked Hamid Mahdi, a weary Baghdad shop owner. “The answer is no. I want the Americans to take the terrorists and sectarian fighters with them.”

Some experts express similar misgivings.

“We created an enemy,” said Omar al-Shahery, a Middle East expert at the Rand Corp. and a former Iraqi deputy director general of defense. “I’m not sure Iraq will be categorized as an ally country 10 years from now. Every day that passes, America’s enemies are consolidating power.”

Yet America’s intervention also brought benefits to Iraq: a fragile democracy, new civil freedoms and an opening to the world for a country once isolated by dictatorship and international sanctions.

()

“It’s easy to forget just how awful a man Saddam Hussein was,” said Danielle Pletka, the vice president for foreign and defense policy studies at the conservative American Enterprise Institute and an influential early Washington supporter of the war. “I think we leave a better country, a country that is less dangerous to its neighbors.”

‘No country likes to be occupied’

The overwhelming Iraqi sentiment toward the U.S. seems as complex as the war itself: We’re angry that you destroyed our country. But please don’t leave yet.

Ali Ghazi, a watermelon vendor in Baghdad’s Karrada neighborhood, expresses the contradictions.

“No country likes to be occupied by another country and be controlled by them,” Ghazi said. “We don’t hate Americans or the American people, but we hate the American military.”

Then he added: “We think things will be worse [if U.S. troops leave] and Iraq will break up. There are many sleeping militias waiting for America to leave.”

Reminders of the war’s toll are everywhere in Baghdad, from buildings still lying in rubble years after the initial American “shock and awe” bombardment to the countless memorial photos of slain Iraqis that hang from light posts.

What’s more, after a drop in sectarian strife over the last two years, violence in recent months has begun to rise ominously: July was the deadliest month for Iraqis since 2008, with almost 400 civilians killed in car bombings and other incidents.

Civilians have bore the brunt of the Iraq war, with more than 113,000 killed in violence since 2003, according to Brookings Institution in Washington. That’s about a third as many Iraqis as are estimated to have perished during Saddam’s regime. Nearly 2 million Iraqis were displaced from their homes, and many of them are still living in filthy squatter camps.

Despite Iraq’s abundance of oil, lines for fuel snake for miles in summer and electricity in all but the richest neighborhoods is on just a few hours a day.

“It’s the simplest things that Americans didn’t achieve in Iraq,” said Zina Abed, a 45-year-old housewife in Baghdad. “After the first Gulf War, Saddam Hussein restored electricity within two days.”

Restoring Iraq’s military also remains an unfinished project.

Iraqi Lt. Gen. Babakir Zebari said U.S. forces should stay well beyond the end of 2011, when all of the remaining American noncombat troops are scheduled to leave the country.

“If I were asked about the withdrawal,” Zebari told reporters last week, “I would say to politicians: The U.S. Army must stay until the Iraqi army is fully ready in 2020.”

Some American political experts also believe the U.S. withdrawal is too swift. They point to the simmering dispute between Kurds and Arabs in the country’s north over land and oil rights and the raw psychological wounds of Iraq’s sectarian civil war, which drove a wedge between Shiite and Sunni Arabs.

“There’s a psychological benefit of just having [U.S. troops] there,” said Michael O’Hanlon, an Iraq expert at the Brookings Institution and the author of the Iraq Index, a statistical and sociological barometer of the situation in the country. “We’re seen as an honest broker. They still have a lot of sectarian wounds that need to be healed.”

Losing the political battle

Meanwhile, the battle for political power in the Iraqi government is just beginning — and some Iraqi and American experts believe Washington has already lost.

A close election in March led to a persistent deadlock in forming a new government. Iran is widely believed to have inserted itself into the process, playing a large role in negotiations with religious Shiite parties, such as acting Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s Dawa Party.

Loath to appear to be meddling in Iraq’s politics, Americans have largely sat on the sidelines, much to the chagrin of many Iraqis.

“The U.S. always underestimates its influence in Iraq, which is a big problem,” said al-Shahery, the Rand expert. “When I was in the Iraqi Ministry of Defense, I saw the U.S. shying away from the influence that they had.”

Yet some of the war’s political defenders in Washington still believe a democratic Iraq can stabilize the Middle East, much as the Allied victory and subsequent reformation of Germany remade Europe after World War II. That’s the view of Zalmay Khalilzad, President George W. Bush’s ambassador to Iraq.

“I think success in Iraq, and the potential impact of that success on the region, would make the investment we made, the sacrifices that have been made — higher than anticipated, clearly — ultimately to have been worthwhile,” Khalilzad said. “But it depends entirely on the success of [Iraqis], and for that we will have to wait for some time to see.”

Gen. Ray Odierno, the top American military leader in Iraq, stopped short of making any predictions about Iraq’s future.

“This is still a very complex place,” he said at a recent press conference. “We’re not going to be sure of the outcome for three or five or 10 years.”