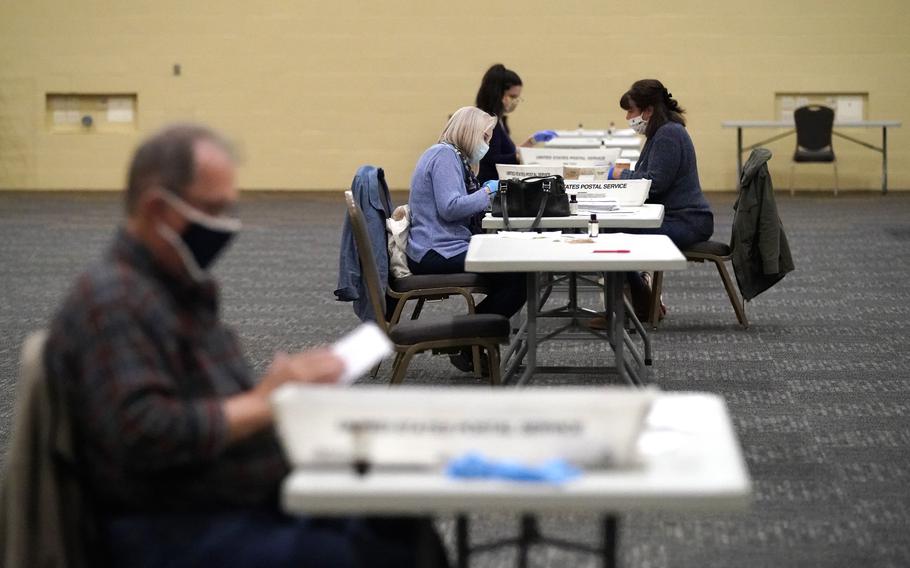

Workers prepare mail-in ballots for counting, Nov. 4, 2020, at the convention center in Lancaster, Pa. (Julio Cortez/AP)

Watching election night on cable or network news is a great national tradition. Memorable moments arise as the networks announce their projections in key states. Anchors and commentators demonstrate extraordinary understanding of the unique politics of hundreds of cities and counties across the country. As the results of the most consequential election on the planet unfold, there’s a powerful sense of shared witness.

But our polarized politics has revealed a serious flaw in election night coverage. As disinformation abounds, it is increasingly important for voters to know how the actual, legally certain election results are determined. And right now, voters are not seeing enough of that information on their screens on election night.

Projections by CNN, Fox and other outlets serve an important function. They give voters a statistically based prediction of who the actual winner will likely be once states complete their careful processes in the weeks after Election Day. But these projections have no official status, and news anchors typically don’t do enough to make that clear. News programs also need to include segments that explain how the actual results are verified and certified.

Four years after November 2020, we still have a dangerous level of disagreement and uncertainty across America about the critical fact of who won that presidential election. By far the main reason for this uncertainty is the unwillingness of Donald Trump to accept his defeat, a defeat confirmed by multiple audits and recounts and by the outcome of more than 60 court challenges across the swing states.

But we should acknowledge that uncertainty arises in part because America has a very complicated presidential election system that can be hard for citizens to really understand. Different rules in every state create differences in how Americans vote and how and when vote counts are verified and certified. Court cases play a critical role in the legal certainty of results but are hard for voters to learn about and understand. And the election happens in two phases — the vote of the people and then the vote of the electors the people have selected — and that combination creates confusion.

There is a risk that network projections on election night can add more uncertainty. Something called a “projection” inherently implies uncertainty, since it could possibly be reversed. And projections suggest subjectivity, since different news outlets reach different conclusions about whether a state is ready or still too close to call.

We cannot let who won the presidency be a subjective question, a matter of opinion — it must be understood as a matter of fact and law. For that to happen, we need to help Americans see and understand the legal processes that do in fact render a certain answer to the big question of who won.

These are the reasons we have cosigned, with a broad, bipartisan array of organizations, an open letter to election reporters and election news anchors. The letter is an initiative of the Election Reformers Network developed with bipartisan support from The Carter Center, the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation Issue One and other organizations.

The letter asks that news organizations use some version of the following phrasing every time a state result is projected: “This is just a projection. The actual results will be final when every vote is counted, officials verify and certify the outcome, and any challenges are resolved in court.”

The letter also urges reporters to reassure voters that accuracy matters more than speed, by using a phrase such as: “Counting the votes takes time, and election results are not final until officials verify and certify the results. We expect (STATE) to certify its official results by (DATE).”

Lastly, the letter encourages election night programs to include brief segments that explain the upcoming post-election verification and certification phases in the key swing states. Such segments could also provide brief explanations of the reason behind the timing of release of results so that delays do not cause concerns. Pennsylvania law, for example, does not allow election officials to pre-process absentee ballots before Election Day, as other states do, and for this reason results may be delayed there and networks likely will not be able to project a winner in Pennsylvania on election night.

There is of course a serious risk that the 2024 election could result in the same division in public opinion that plagued 2020, with one side refusing to accept the legally validated outcome. But even if that happens, how reporters and news networks talk about the real results process could have a significant impact on reducing susceptibility to ungrounded claims.

Americans learn a lot about our country on election night, as anchors zoom in on the political details of pivotal swing counties across the states. This year it’s time for Americans to also learn a lot about America’s election process on election night.

Kevin Johnson is the executive director of the Election Reformers Network. Nick Penniman is the founder and CEO of Issue One and author of “Nation on the Take: How Big Money Corrupts Our Democracy and What We Can Do About It.”