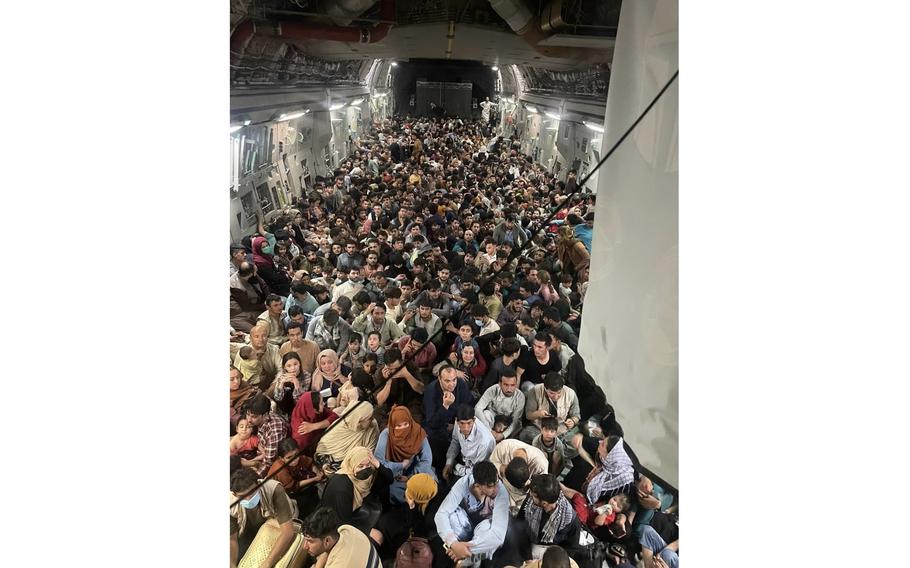

A U.S. Air Force C-17 Globemaster III transports over 820 Afghan citizens from Kabul’s Hamid Karzai International Airport in Afghanistan, Aug. 15, 2021. (Stars and Stripes)

The terrible disaster of the collapse of the Afghanistan government and sweeping Taliban victory three years ago was a reversal for the United States and the international community, and a serious leadership failure by the Biden administration. However, the collapse does not have to be a strategic defeat for the U.S.

Let me explain why. The anniversary of the debacle is an appropriate time to do so.

The failure of the administration adequately to prepare for this scenario was devastating. The background of the debacle has been investigated, but not thoroughly or publicly.

The fact that the Democrats held majorities in both houses of Congress, along with the White House, means the party’s congressional leaders did not pursue aggressive fact-finding hearings. However, the leaders’ power is limited, and the scale of a failure this significant provides powerful incentive. Republicans now have a narrow House of Representatives majority and continue to press.

Most striking is that the American withdrawal from Afghanistan unfolded contrary to customary procedures, as well as common sense. Normally, civilians leave first, then the military, with a rear guard securing exits as long as necessary.

The explanation is that clearly no one at the top of the administration believed Afghanistan’s government and military would disintegrate immediately. Consequently, there was no preparation for handling this terrible worst-case development.

Predictably, various agencies aggressively leaked to the media that they warned the White House this collapse was likely to happen. Skepticism is the right attitude toward such self-protection, especially in this case.

The Biden administration apparently failed to coordinate withdrawal with our allies. A substantial international coalition overthrew the Taliban regime and occupied the country following the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States. The U.S. led this United Nations and NATO effort, but many nations have been involved. This again is a prime topic for in-depth serious investigation.

There is also a challenge to learn and use this failure to strengthen as well as repair relations with our closest allies. We should devote sustained attention to working-level military and intelligence cooperation, and make the priority public.

Reports are impressive of British and French military patrols in Afghanistan operating beyond the Kabul airport and successfully rescuing their citizens, Afghan nationals and some Americans. Permitting American forces guarding the airport to join them should have been done. In April 1975, as South Vietnam collapsed, U.S. officials emphasized efforts to rescue our citizens and allies.

“Someone to talk to” is how McGeorge Bundy, President John F. Kennedy’s national security adviser, described Anglo-American rapport. Fundamental affinity helped forge an enduring special relationship during the total struggle of World War II.

Commentary on Afghanistan regularly referred to the disastrous Soviet invasion and ultimate defeat in the 1980s, but usually overlooked the earlier history of British engagement. During the 19th century, the British experienced military defeat, but eventually achieved influence. Condemnation of President Joe Biden by Britain’s Parliament provides powerful evidence for necessary repair of relations.

Britain’s influence in Afghanistan proved to be of particularly important strategic help during World War II. That nation remained neutral, reinforcing the importance of the then-colony of India. The grand goal of Germany and Japan linking forces in South Asia failed.

The two-decade occupation of Afghanistan has brought extensive economic and social modernization. That clock cannot be turned back completely, and economic aid to the nation provides useful practical leverage.

Electronic surveillance and human agents are essential to monitor the Taliban. No doubt this is happening, but should be a top priority.

The effort to transform Afghanistan was misguided. In future realism, calculated diplomacy and selective aid should guide policy — not failed utopianism.

Learn More: Hans Morgenthau, “Politics Among Nations.”

Arthur I. Cyr at Carthage College is the author of “After the Cold War,” “Liberal Politics in Britain,” and other books.