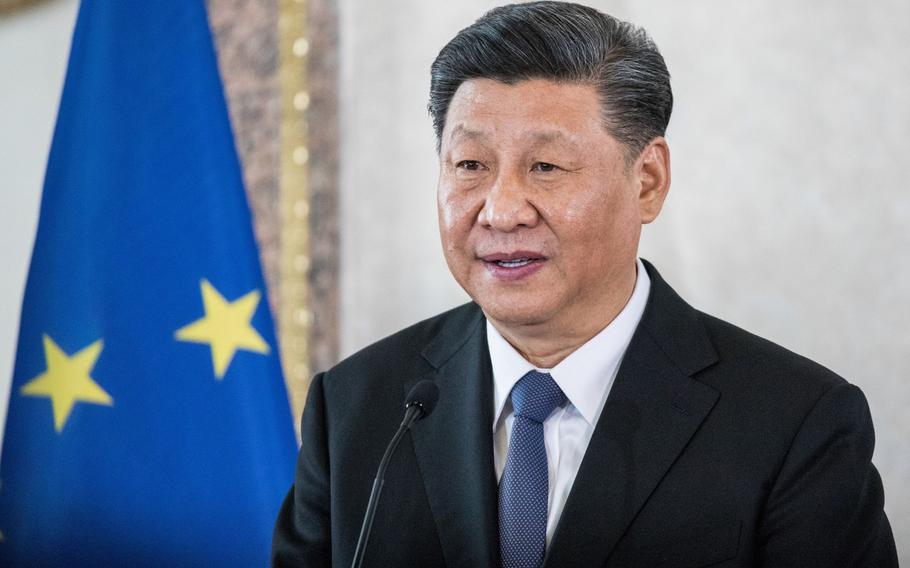

Xi Jinping in Rome on March 22, 2019. (Alessia Pierdomenico/Bloomberg)

In an era fraught with escalating global tensions, the reinvigoration of arms control is becoming more critical than ever.

The U.S.-China nuclear talks ahead of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit were a crucial step away from years of tension over territorial encroachment, economic protectionism, nuclear expansion, and termination of military-to-military communications. Congress, not so far removed from the balloon debacle, should take note, as they have failed to chart a realistic path forward of their own.

The White House, on the other hand, secured a rare nuclear diplomacy win in November, with China and the U.S. pledging to ban artificial intelligence from nuclear control and deployment systems. With no such vision for proactively thawing relations and vitriol filling the nuclear messaging vacuum, Congress has nothing to show for its efforts thus far. Arms control did not even warrant a mention in its only consensus report of late. Of course diplomacy is not a panacea to every foreign policy challenge, but members should be looking to safeguard their constituents from an arms race, not march them into the throes of a new one.

To that end, last year the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission was charged with delivering a bipartisan consensus report reviewing American military strength, assessing Russian and Chinese military threats, and making force posture recommendations. These could include additional conventional or nuclear capabilities.

In this political climate, crafting a report representing only shared conclusions is a heavy lift. Predictably, it sidelined arms control, omitted a baseline analysis of nuclear weapons’ role in deterrence, ignored domestic production and cost limitations, and neglected discussing potential arms race triggers.

What they could agree on was a laundry list of expanded capabilities, including increasing the number of deployed nuclear warheads. Despite commissioner disagreement on the inevitability of a nuclear buildup, the report will likely come up as evidence for such an agenda. For example, when the U.S. Strategic Command released a letter on China surpassing the U.S. in Intercontinental Ballistic Missile launchers, House Armed Services Committee Chairman Mike Rogers cited it to argue for formal withdrawal from New START. He omitted the fact that the U.S.’ stockpile of 3,700 warheads would still dwarf the Pentagon’s worst-case projection for China’s arsenal, 1,500 ICBMs by 2035.

Nuclear superiority is not the cure-all it appears to be. Historical analysis suggests the advantages of nuclear superiority don’t hold when facing adversaries with vastly weaker arsenals, because they must show more resolve to survive. Achieving a level of superiority that avoids this problem would still take many years, allowing Russia and China the time to respond in kind. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin has himself acknowledged that pursuing numerical superiority of nuclear weapons could spur an arms race. Expanding capabilities rather than quantity, like AI-enabled sensors, can also erode deterrence by increasing perceived risk and incentivizing a first-strike or buildup to offset this risk.

Despite the report’s veneer of consensus, strong divergent opinions remain. Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi, ranking member of the House Select Committee on U.S.-China Strategic Competition, voiced disagreement with his Republican colleagues’ discomfort with high-level U.S.-China dialogue. Indeed, the consensus is to act against the challenges China poses, but members diverge on means and whether diplomacy is feasible and/or desirable. Crucially, with internal pressure on Republicans to take a tough stance on China, there’s no clear incentive for individual members to prioritize arms control to keep their seats.

The recent talks are a vital mobilization opportunity in a geopolitical climate the commission considered too “bleak” to prioritize arms control. The administration, perhaps due to a degree of political necessity, at least saw potential. While their outcome was not a concrete breakthrough, arms control diplomacy seldom achieves linear progress. The 1986 U.S.-Soviet Reykjavik summit was seen as a failure after an ambitious proposal unraveled due to disagreements on missile defenses. Just one year later, the Washington Summit yielded the Intermediate-Range Forces Treaty.

It is important to remember that meaningful arms control diplomacy always takes time. The U.S. finally destroyed all of its chemical weapons in 2023, just shy of the disarmament deadline 25 years after the world banned them. That’s why the U.S.-China talks are so important, and why momentum must not slow down now.

While there has been some silence about the rumored U.S.-China declaration, AI remains a central topic for Congress and the Department of Defense. Sen. Ed Markey and Rep. Ted Lieu’s Block Nuclear Launch by Autonomous Systems Act would codify the key sentiment of the rumored U.S.-China declaration into law, a great way to keep the process moving as U.S.-China bilateral diplomacy efforts continue.

Congress, the White House and the public should be clamoring for a bipartisan commitment to arms control diplomacy on par with the attention dedicated to a military buildup. Failing to seize this generational opportunity would be a disservice to not just the United States, but the world.

Sofia Guerra is a program assistant for Nuclear Disarmament and Defense Spending at the Friends Committee on National Legislation.