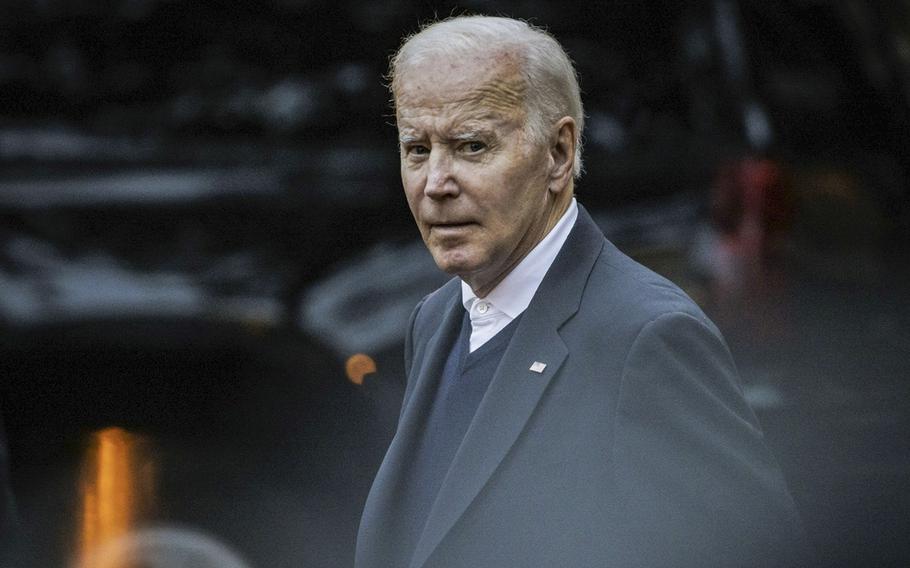

President Joe Biden leaves Holy Trinity Catholic Church before attending the Phoenix Awards Dinner in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 1, 2022. (Samuel Corum/Bloomberg)

The war in Ukraine is reaching a new phase, and U.S. strategy is undergoing an important shift. Fears of Russian nuclear escalation are receding as fears of a long war featuring unrelenting attrition are increasing. So President Joe Biden’s administration is ramping up support for Ukraine now in hopes of producing an eventual diplomatic resolution — an “escalate to de-escalate” strategy that may prove very difficult to execute.

Nearly a year into the war, uncertainty about its course is greater than ever. For the first six months, Russia had the initiative: The major questions were when, where and with what success it would attack. Over the following five months, Ukraine had the initiative, and analysts tried to divine the location and prospects of its counteroffensives.

Now, it’s harder to tell what comes next and who has the edge. Both sides may be preparing new offensives. And both sides are dealing with a mix of battlefield losses and new capabilities that make it more difficult to discern their relative strengths.

Russian President Vladimir Putin probably believes that his best ally is time. If he can keep hammering Ukraine’s infrastructure, while at least holding what he has on the battlefield, perhaps he can create a protracted slugfest in which Russia’s superior manpower will prove decisive.

Ukraine sees time as its enemy. It must exploit Russia’s weakened, poorly equipped forces now, before additional newly mobilized Russian troops arrive on the battlefield, before Russian defense production hits high gear, and before support from Kyiv’s Western backers dissipates.

The Biden administration is only guardedly optimistic about Ukraine’s prospects. The easiest gains at the expense of an overstretched Russian army may already have been had. Putin is defending a shorter front with a larger number of troops. That makes routing Russia from every inch of Ukrainian territory difficult, even if Kyiv’s committed, creative military can go further than it has to date.

So the U.S. administration is updating its strategy in three ways.

First, it is better defining American war aims. In December, Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced that the U.S. is committed to helping Ukraine liberate lands lost since February 2022, but not necessarily every inch of territory Putin has stolen since 2014. Washington’s goal is a Ukraine that is militarily defensible, politically independent and economically viable; this doesn’t necessarily include retaking difficult areas such as the eastern Donbas or Crimea.

Second, the U.S. and its allies are sending Ukraine more sophisticated weapons: armored personnel carriers, Patriot missiles, and tanks that can bust through layered Russian defenses. Washington is also moving toward providing longer-range munitions that can pulverize Russian rear areas: The ground-launched small diameter bomb, likely to be part of an upcoming assistance package, has nearly twice the range of the HIMARS rounds Ukrainian forces have used to devastating effect. The next debate may involve sophisticated aircraft: Biden recently said the U.S. won’t provide F-16 fighters to Ukraine, but that’s also what he said about providing American tanks up until the moment he changed his mind.

Third, Biden may not envision Ukraine liberating Crimea by force, but he has reportedly become more supportive of strikes against Russian targets there. Could hitting Crimea, which is central to Putin’s narrative of Russian resurrection under his rule, trigger escalation?

Perhaps. But Putin has bluffed about escalation so many times that his threats are losing credibility. And precisely because Crimea is so important to Putin, threatening him with its loss may be the best way to force him to negotiate seriously.

Although these various policy shifts seem to cut in opposite directions, there is a unifying logic. The U.S. doesn’t want the war to drag on forever, because it is turning much of Ukraine into a wasteland while taking a toll on Western treasuries, arsenals and attention.

So Biden aims to help Ukraine dial up the pressure on Russian forces, and perhaps shift the lines further in its favor, as a pathway to negotiations after the next phase of the fighting has ended.

There’s nothing simple about this strategy, as shown by the recent trans-Atlantic fracas over who would give Ukraine what sort of tanks. The U.S. managed that issue adeptly in the end, pledging to send 31 advanced Abrams tanks months from now as a way of freeing up the delivery of perhaps hundreds of European tanks in the coming weeks. But that isn’t the only challenge.

Biden is betting that there is a sweet spot at which the Russians will be reeling badly enough to negotiate but not to escalate, and at which the Ukrainians — having won a stronger position — will agree to stop short of what they desire and deserve.

That’s possible, although far from certain: It would require both sides to conclude that continuing the war will mostly hurt them, and to identify some nifty diplomatic formula to bridge, or simply obfuscate, the gap between their respective positions on issues like Crimea.

Biden’s updated strategy is an intelligent effort to grapple with a shifting battlefield and to figure out how military progress can facilitate a settlement that sticks. That doesn’t necessarily mean it will work.

Hal Brands is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. The Henry Kissinger Distinguished Professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, he is co-author of “Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China” and a member of the State Department’s Foreign Affairs Policy Board. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.