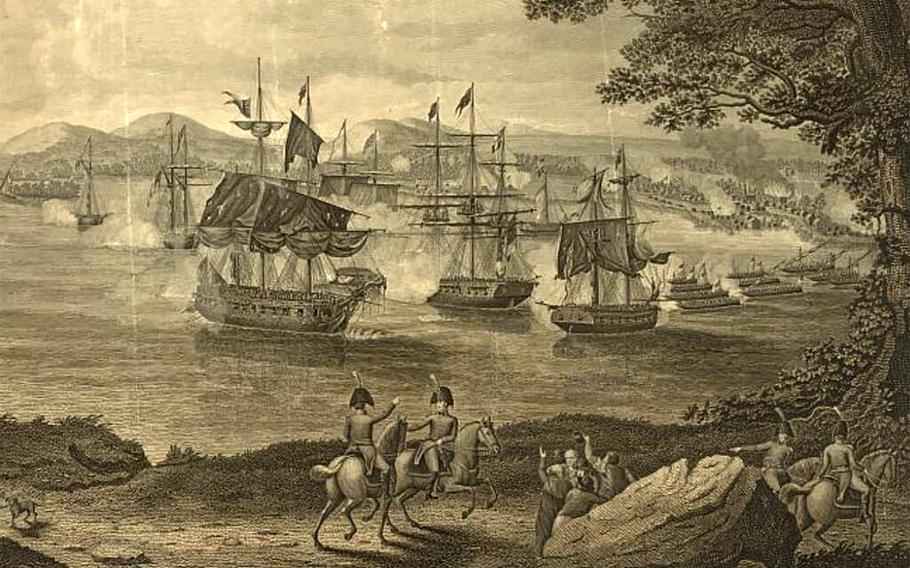

An 1816 engraving shows the naval battle of Plattsburg on Lake Champlain on Sept. 11, 1814, between American and British forces. Among the Americans was a young doctor from Maine, John Briggs, who was severely wounded in the ankle but managed to keep on caring for the wounded in his charge. (Library of Congress)

(Tribune News Service) — Cannon shots crackled and snapped through the ship’s rigging, high overhead. Furious shells exploded all around. The dead and dying lay strewn across the U.S.S. Saratoga’s wooden deck while the Battle of Plattsburgh raged on Lake Champlain in the fall of 1814.

Amid the chaos was a young doctor from Maine, John Briggs, doing what he could to save lives. The wooden battleship was still unfinished. Briggs was forced to care for the wounded out in the open, near the mainmast, amid the heat of war.

While lifting an incapacitated man, a British broadside slammed into the ship. Briggs’ assistant was killed instantly. At the same time, the explosion drove a large wooden splinter deep into Briggs’ ankle. Despite his bloody injury, the doctor carried on until the battle was won and the British retreated back into Canada.

The wound was serious. Briggs was unable to wear a boot for a year and it hobbled him for the rest of his life.

He died in 1837 at the age of 46. Afterwards, Briggs’ wife remarried and most of his family moved off to greener pastures in Illinois. His marble stone, worn by nearly 200 Maine winters, is now almost unreadable in Portland’s Eastern Cemetery.

Over the years, Briggs, and his service to his young country, were forgotten.

Now, 207 years after his heroic deeds — thanks to a loose-knit network of unpaid volunteer history sleuths in Maine, Wyoming and Texas — Briggs’ story is coming to light. This month, a family member will visit his bones for the first time in more than a century. They’ll come thousands of miles to say thank you and place a War of 1812 medallion on his no-longer-forgotten grave.

“I wish I could shake his hand and thank him for his service so long ago,” said Portland historian Ron Romano, who helped research Briggs’ life and recently wrote a scholarly paper about him. “He was clearly a caring soul.”

Briggs’ life and service was first rediscovered in Sheridan, Wyo., where Auburn native Tammy Mansfield is state president of the National Society United States Daughters of 1812. The organization is dedicated to preserving history and increasing understanding of the United States’ least-known official war.

To join, members must prove direct lineage to someone who served in a civil or military capacity during the conflict.

While helping a friend, Daphne Weitzel, research her family for that purpose, Mansfield came across Briggs, one of Weitzel’s distant ancestors.

As a War of 1812 researcher, Mansfield specializes in getting military tombstones for previously unmarked veteran’s graves. She’s done it dozens of times.

To see if Briggs needed one, she hopped on the popular website findagrave.com, where millions of burial sites have been cataloged and photographed. But there was no online picture of Briggs’ grave.

That’s where Romano comes into the story.

He likely knows more about Portland’s Eastern Cemetery — and its permanent residents — than anyone else alive. Romano literally wrote the book on the burial ground and is the author of numerous other historical research papers.

“It truly started with a phone call from Tammy,” he said.

Romano told Mansfield that Briggs had a stone but no official War of 1812 marker. As he looked further into the matter, a picture of Briggs’ life emerged.

Briggs was born in Gorham in 1791 and married Dorothea Boynton of Cornish while both were still teenagers. They would go on to have at least 10 children together.

In 1813, near the start of the war, Briggs was commissioned a surgeon’s mate. By the next year, he was listed in military records as a doctor.

After the war, he practiced medicine in Portland and sold his own blend of medicinal bitters. In 1832, he applied for a military disability pension. He had trouble getting it because he’d forgotten to list himself among the wounded after the battle. It was eventually approved at $25 a month but Briggs died soon after of unknown causes.

Dorothea remarried and was widowed a second time before moving west to LaSalle, Illinois, with most of her children.

Romano’s research eventually led him to Steven Strout of Fort Worth, Texas.

“Briggs was my fourth great grandfather,” Strout said.

Strout is also a history buff and the keeper of his family’s lore. He provided Romano with a trove of documents, including a letter Dorothea wrote to Briggs on Oct. 13, 1814, just after the Battle of Plattsburgh.

In it, she asks him to come back to Maine soon.

“I hope you will think of the unhappiness of your wife and get discharge[d] and come home,” she wrote. “Your little children are well and [talk] much about you and [ask] when will Par come home.”

Strout also had a drawing of Briggs, which is as close as anyone can come to meeting him, face-to-face.

Together, the three former strangers — Mansfield, Romano and Strout — managed to pull Briggs and his wartime service out of historical darkness.

On July 31, Strout will fly further north than he’s ever been before, to mark his ancestor’s grave with a simple gold medallion showing an eagle and anchor. A flag will then be placed in it, letting passersby know Briggs served in the War of 1812.

“It’s moving that people are still thinking about him,” Strout said. “It’s brought him back to life.”

It’s exactly the kind of sentiment that keeps Romano and Mansfield digging through historical records, one grave at a time, in their unpaid labor of love.

“It’s documenting the past and preserving it for the future,” Mansfield said. “Education is everything, so you don’t forget to remember.”

As for Weitzel, whose quest for a genealogical link to the War of 1812 started the whole process: It worked.

“Yes, I’m a member,” she said.

Weitzel now counts herself among the volunteer history detectives who bring veterans like Briggs back to life.

“I’m the newbie but now I’ve got the bug,” Weitzel said. “I’m going through boxes and looking at old photo albums — and I’m proud we’re doing this.”

Romano waxes a bit more philosophical on the subject.

“They say you die three times,” he said. “Once when your heart stops beating, once when the last person who remembers you dies and again the last time someone utters your name — and I don’t think anyone had said John Briggs’ name in a long, long time.”

The public is invited to the medallion ceremony at 11 a.m. on Saturday, July 31, at Portland’s Eastern Cemetery. The rain date is the following day.

To read Romano’s full paper on Briggs visit the Spirits Alive website.

(c)2021 the Bangor Daily News (Bangor, Maine)

Visit the Bangor Daily News (Bangor, Maine) at www.bangordailynews.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.