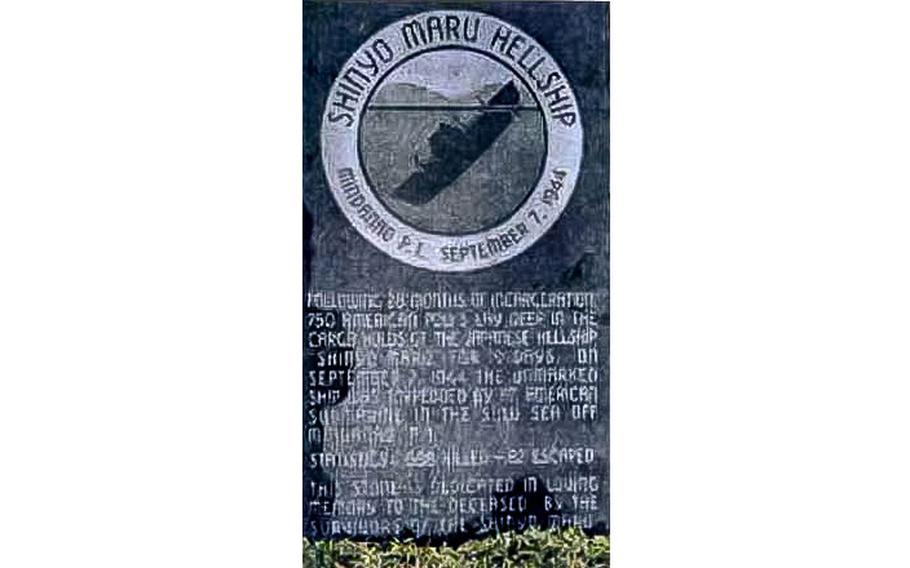

A plaque in San Antonio, Texas, dedicated to the survivors of the POW Hell Ship Shinyo Maru, sunk by USS Paddle (SS-263), is seen on Sept. 7, 1998 on the 54 anniversary of the ship’s sinking. (WikiMedia Commons/U.S. Navy)

(Tribune News Service) — To several Northeast Pennsylvania prisoners of war held captive in its holds, the steamship Shin’yō Maru was a hell ship.

It and other vessels earned that nickname and reputation during World War II, when Imperial Japan used captured ships as floating prisons to move POWs subject to barbaric conditions and savage mistreatment. Many were killed in the wake of attacks by Allied forces.

Such was the fate of six local POWs who perished when the USS Paddle — an American submarine unaware its target carried prisoners — torpedoed the Shin’yō Maru as it led a convoy sailing for Manila, Philippines, on Sept. 7, 1944.

In recognition of National POW/MIA Recognition Day, which this year is Sept. 15, the nonprofit Stories Behind the Stars is honoring those men and the rest of 34 Pennsylvania POWs believed killed in the Shin’yō Maru incident. Volunteers with the nonprofit drafted memorials to each of the fallen.

Northeast Pa. veterans among the 668 POWs killed in the incident

• Staff Sgt. Carl R. Jones, Clarks Summit.

• Pvt. Joseph M. Zarzecki, Scranton.

• 2nd Lt. William Williams Jr. Newspaper records identify Williams as a Taylor native. His family later lived in Tunkhannock.

• Pvt. August J. Grigal, Kingston.

• Pfc. Paul J. Martin, Coaldale, Schuylkill County.

• Cpl. Martin McGrath, Frackville.

While sometimes sparse, newspaper records and the Stories Behind the Stars profiles paint a picture of each man’s life and service. They all enlisted before the United States entered World War II, and fought to defend the Philippines when the Japanese invaded in December 1941.

The profiles note Jones, Zarzecki, Williams and Martin became infantrymen in the defense of the Bataan Peninsula; McGrath’s 31st Infantry Regiment covered the withdrawal of forces to the peninsula.

Grigal, whose family moved to Kingston when he was a boy, worked as a machine cleaner at Liberty Silk Mill before entering the service. He was captured in the Philippines and sent to a Japanese POW camp at Davao, his profile notes.

When Allied forces ultimately surrendered at Bataan on April 9, 1942, roughly 75,000 Filipino and American troops became POWs. The Bataan Death March followed, during which captives were brutalized, beaten and sometimes bayoneted and shot.

A March 3, 1945, newspaper report of Jones’ death in the Shin’yō Maru incident notes he survived the Bataan Death March. The same article notes Williams perished in the sinking.

“(Jones’) mother received a postcard from him only two days before the arrival of the notice of his death from the War Department,” according to the article. “It was the first word she received from him since last Easter and ironically stated that he was well.”

Nearly 300 of the 750 Allied prisoners carried aboard the Shin’yō Maru had survived the death march. The Stories Behind the Stars profiles, the product of researching other sources, describe the carnage that unfolded when the ship came under attack Sept. 7, 1944, when American torpedoes fired from the USS Paddle struck it.

“The POWs had heavy obstacles falling on them from above,” they read. “Many were lying with their bodies shattered and bleeding. Some were able to go above due to the damage to the hatch doors and witnessed many Japanese lying dead on the deck. Imperial Japanese guards opened fire on the prisoners using captured Thompson submachine guns. Over 100 men were able to fight their way through the guards and abandon ship.”

Some of those men were recaptured and executed; 83 reportedly escaped to shore as the Shin’yō Maru sank, though one died the next day. In all, 668 were killed.

Survivors were ultimately evacuated.

The fate of Martin, the Coaldale man, “remained somewhat of a mystery to his mother,” according to a newspaper article from September 1945.

She received word the previous October that Martin had been aboard a destroyed Japanese freighter carrying POWs, but later received an undated card from her son sent from a prison camp.

According to a report in The Morning Call newspaper, the card read: “I am interned at Philippine Military prison camp No. 2. My health is excellent. Hoping to see you soon. All is well. Hoping everybody is well at home. Love to all. Paul.”

His mother was ultimately informed that Martin was lost in the sinking Sept. 7, 1944, “and that he must be considered dead,” a different newspaper article notes.

Stories Behind the Stars Pennsylvania Media Director Chris Moyer, who’d never heard of Japanese hell ships before the nonprofit’s project, said the men who perished in the Shin’yō Maru tragedy had already “gone through hell” as POWs.

Their stories were appropriate to share on National POW/MIA Recognition Day, in keeping with the broader mission of the nonprofit, he said.

“Broadly there are over 400,000 World War II fallen and Pennsylvania was home to about 31,000 of them,” Moyer said. “We think it’s vital to make sure that their stories are told.”

(c)2023 The Citizens’ Voice (Wilkes-Barre, Pa.)

Visit The Citizens’ Voice

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.