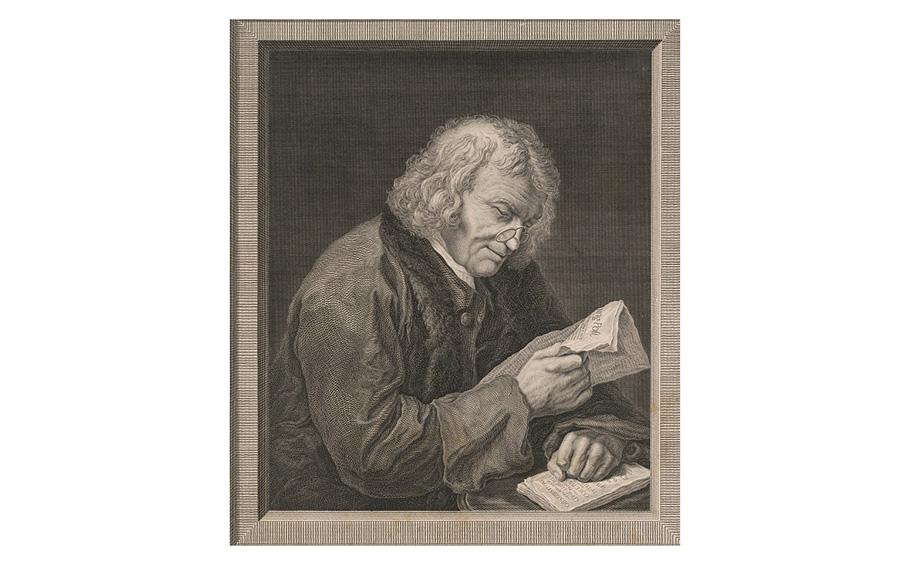

An engraved portrait by Stephen Elmer and Thomas Ryder shows Benjamin Franklin reading. (Library of Congress)

In 1772, a small group of radicals, mostly in Boston and New York, was pushing for American independence.

Benjamin Franklin was not among them. He was in London, as he had been for the better part of two decades, serving the British Empire as deputy postmaster. As a scientist, inventor, writer and publisher, Franklin was the most famous and well-respected person ever to come from the American colonies. Plus, he was witty and fun at parties.

Franklin didn't like the taxes imposed on the colonies but at this point did not support independence, preferring instead to advocate for the colonists before the British Parliament. Then he got hold of some very private letters.

There is little if any resemblance between the statesman Franklin and Jack Teixeira. Teixeira is a 21-year-old member of the Massachusetts Air National Guard now charged with leaking a trove of classified documents that has rocked the defense and intelligence world. But if stories from some of Teixeira's online friends, who allege he meant to share the intelligence with only a small group of young men, are to be believed, then he and Franklin share at least one situation: Both of the intelligence leaks spun wildly out of their control.

For Franklin, it started with a packet of letters from the Massachusetts colonial Gov. Thomas Hutchinson and his lieutenant Andrew Oliver. Historians don't know who leaked the letters to Franklin, but what he read in them was alarming. Hutchinson and Oliver opposed colonists' demands for equal rights with the British. They complained of the unruly Massachusetts assembly and suggested the governor be given more power over them and that more British troops be sent to put down the unrest.

Franklin thought the letters mischaracterized the situation in Massachusetts, thus misleading the entire British Parliament, and that if certain members of the Massachusetts assembly knew about this, they would focus their anger more accurately on Hutchinson than on the British authorities who had been misinformed by Hutchinson. So he sent the packet of letters overseas to Thomas Cushing, the speaker of the assembly, with strict instructions about with whom the speaker could share them.

At first Cushing honored Franklin's request to share the letters with only a few specific people, though he asked Franklin whether he could publish them. Franklin said no, he could not. Unfortunately for Cushing, Samuel Adams was one of the authorized viewers, and Adams, as one of the radicals, did not care about respecting Franklin's request. He began writing about the existence of the letters and his opinion of them. By mid-June 1773, the letters were published in full in the Boston Gazette.

Demonstrations and riots ensued, with demands for the removal of the governor. The uproar also contributed to the Boston Tea Party six months later, in which a mob of radicals dumped British tea into Boston Harbor.

In London, the search was on for the leaker whose actions had caused such mayhem. The original recipient of the letters, Thomas Whately, had died, but his brother Charles Whately accused a customs officer named John Temple. Temple denied the charge and challenged the brother to a duel.

The duel was a "clumsy, almost comical affair," according to historian Kenneth Lawing Penegar in his book "The Political Trial of Benjamin Franklin: A Prelude to the American Revolution." Temple, overweight and nearly deaf, began the fight before either man's aides had arrived. Also, it was raining, and the two men thrashed about in the mud with their swords for an hour before a passerby stopped them. Still, Whately left wounded, and soon another duel was planned.

Franklin, probably beside himself and hoping to stop further bloodshed, decided to come clean. On Christmas Day in 1773, he published a confession in a London newspaper. Yes, he leaked the letters, he wrote, but really, correspondence between these officials should have always been public anyway, and he was only trying to show the colonists and the Parliament that they had more in common than they thought. He was just trying to help!

In January, Franklin was summoned to appear before the privy council, the king's most senior advisers. To make matters worse, a few days before his scheduled appearance, the news about the Boston Tea Party hit British shores. The solicitor general, who presided over the hearing, excoriated and insulted him at length before firing him from his post.

Franklin, his reputation destroyed, returned to the colonies in March 1774. Rather than change people's minds about the conflict between the colonies and the empire, the whole affair had changed only one mind: his own. He now supported American independence.