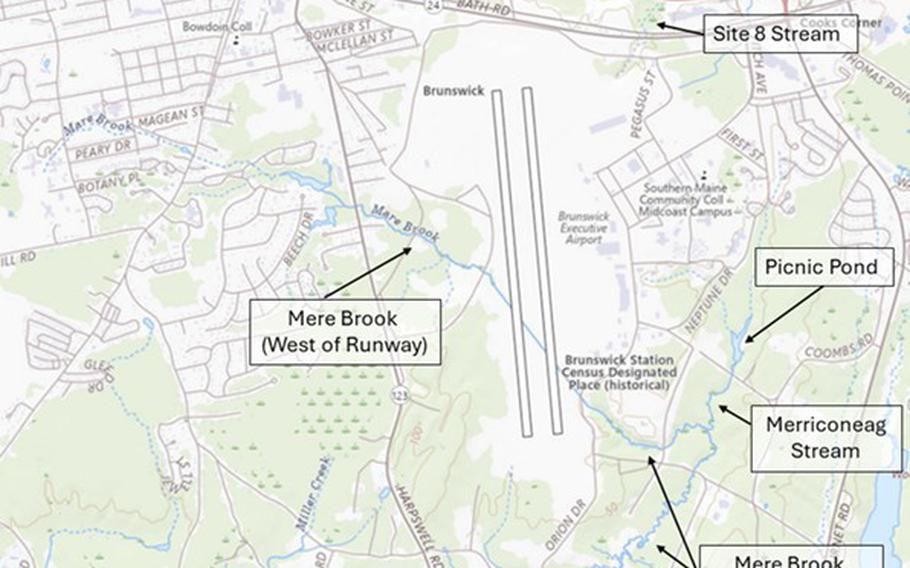

A map of waterbodies on and around the former Naval Air Station in Brunswick that may be contaminated by chemicals from a spill at the former Naval Air Station in Brunswick, according to an advisory by the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (Maine DHHS)

(Tribune News Service) — The concentration and diversity of toxic forever chemicals released in last week’s firefighting foam spill at the Brunswick Executive Airport is even higher — and according to some scientists, even worse — than what was first announced by the Maine Department of Environmental Protection.

The Aug. 19 spill, which is believed to be among the nation’s worst in 30 years, is the latest stain on the long, dirty environmental history of the highly contaminated former Brunswick Naval Air Station. The spill was the topic of a public meeting in Brunswick on Thursday.

In its Monday progress report, Maine DEP shared the initial test results of the foam concentrate, the concentrate mixed with water, and the inlet and outlet of the unlined drainage ponds that lead from the airport to the creek that empties into Harpswell Cove and then Casco Bay.

In that update, Maine shared the off-the-charts concentration of one particularly nasty forever chemical — 3.2 billion parts per trillion of PFOS — which it identified as the primary compound in the aqueous film-forming foam, or AFFF, that was hooked up to the hangar’s faulty fire suppression system.

Scientists question why Maine DEP chose to express PFOS concentration as 3,230 parts per million and not 3.2 billion parts per trillion. The state uses parts per trillion to measure forever chemical levels in its drinking water. It’s the same number, just expressed differently. One looks big, one looks small.

They also question why Maine DEP’s update only shared the PFOS number. The lab results showed 1.1 billion parts per trillion of 13 other forever chemicals in the concentrate, including 69 million parts per trillion of PFOA, the forever chemical with the most epidemiological evidence of human harm.

Gail Carlson, head of Colby College’s Buck Lab for Climate and Environment, had this reaction: “Yikes!”

“I am very concerned about these other PFAS at such high levels,” said Carlson, an assistant professor who studies the human health impacts of forever chemicals. “The risk for human exposure is likely when environmental contamination occurs, which the pond results show.”

The pond inlet has over 1 million parts per trillion of PFOS and 231,000 parts per trillion of 12 other forever chemicals, including 14,100 parts per trillion of PFOA. At the outlet, due to dilution and the different migration rates, levels fall to 701 parts per trillion of PFOS and 1,456 parts per trillion of all forever chemicals.

To put that in context, Maine’s interim drinking water standard caps the amount of six different forever chemicals, including PFOA and PFOS, at no more than 20 parts per trillion. The water leaving the pond on Monday, the day of the spill, came in at 1,086.29 parts per trillion for those six forever chemicals.

Maine plans to lower its drinking water limits to match the new federal PFAS limits of no more than 4 parts per trillion.

“It’s pretty clear the state wants to control the narrative on this, making the numbers look as small as it can so people don’t get scared,” Carlson said. “I don’t want to be an alarmist, but I’d be scared if I lived there ... I’ve been working in this field for a long time and I’ve never seen numbers like these.”

But a department spokesman said DEP chose to use parts per million instead of parts per trillion for “ease of readability.” It used PFOS as an example because it is the primary forever chemical in the concentrate, and it had the highest concentration detected in the samples, said Deputy Commissioner David Madore.

The measurements were taken to illustrate the differences between the concentrate and how it begins to move through the surface water system to determine how well the local, state and federal response effort is working, Madore said.

He said DEP couldn’t comment on the scientists’ concerns, noting it was not a party to the conversations.

State and local officials have reassured the public that the public drinking water supply is safe because it draws upon aquifers located far away from Brunswick Landing. The local water district has increased its PFAS testing since the spill. An alarm system would prevent a PFAS spill into an aquifer from reaching any tap.

The historical path of contamination at the former naval air station, which was designated a Superfund site in 1987 due to chemical contamination caused by ordnance detonation, suggests the chemicals that are seeping through the soil as a result of the spill will travel away from private wells toward the ocean.

If she lived near the airport, Carlson said, she’d get her well water tested immediately, by the end of day, and she’d plan to test it every week for a while, even though it costs $350 a test and takes a month to get the results back. She said she’d test her well water, her soil and her blood.

Carlson said the environmental risks of last week’s “public health tragedy” can only be fully understood through long-term water, soil and air testing. The state must expand its testing beyond the former base, the ponds, or the cove, she said — it must test the private wells, soil, and blood of those living nearby, too.

Despite downplaying the risk to private wells, DEP said last week it will sample some, but not all, private wells in the nearby residential neighborhoods. On Wednesday, DEP said it had decided to sample some wells east of the spill site “based on Maine’s complex hydrogeology and historical test data.”

The historical record of PFAS contamination at the base is murky even though it’s a Superfund site. The base closed in 2011, before environmental agencies recognized forever chemicals as a public health risk. As a result, environmental records are incomplete, at best.

It wasn’t until two years ago that Maine passed a law requiring people to report AFFF discharges to the state, so state records before that are spotty. But federal records show last week’s Brunswick spill is the biggest accidental foam discharge in Maine since it began keeping records in the 1990s.

But it’s not the only one, and it’s not even Brunswick Executive Airport’s biggest foam concentrate spill.

Last week, a malfunctioning fire suppression system discharged 51,450 gallons of firefighting foam 4 to 5 feet deep in Hangar 4, emptying into the sewer and stormwater drains and bubbling up through the manhole covers in the parking lot and in nearby drainage ponds.

In 2019, a regular test of the fire suppression system in the same hangar went bad when someone forgot to close the drain that was meant to keep the foam contained in the hangar and out of the sewer. Airport and state officials claim the mishap resulted in a few dozen gallons being spilled, not tens of thousands.

But David Page, a retired Bowdoin College chemistry professor and local representative to the advisory board overseeing the Navy’s base cleanup, took issue with the state and airport’s characterization of the 2019 spill, noting it elevated PFOS levels in the ponds out into Mere Creek for about two years.

In 2000, back when the Navy still operated a 3,100-acre naval air station there, a power outage knocked the fire suppression system in Hangar 4 offline, spilling about 500 gallons of foam, according to a Coast Guard National Response Center spill record. All but five gallons were recovered.

In 2012, about 2,000 gallons of AFFF concentrate inside a fire suppression tank in Hangar 6 went down the sewer drain in the hangar because of a faulty valve. The fire system was never triggered, and water did not mix with the concentrate, so the amount of foam doesn’t compare to last week’s 51,450 gallons.

But the amount of straight-up AFFF — which is the source of the forever chemicals — that drained into the sewers dwarfs the amount of AFFF mixed into Monday’s larger foam spill. Yet the 2012 spill didn’t crack any state or federal inventory because forever chemicals weren’t deemed hazardous then.

The only mention of that spill is recorded in 2012 sewer district board meeting minutes. At the time, the sewer district manager was worried about the damage the foam backup could cause to the sewer system pumps and the cost of using defoaming agents, not the potential environmental risk.

Aqueous film-forming foam is used by firefighters to fight high-intensity fuel fires at military bases, civilian airports, fuel terminals and industrial plants that use a lot of chemicals, such as paper mills. The foam forms a film or blanket over the fire, depriving it of the oxygen it needs to burn.

Firefighting foam is the most common source of forever chemical contamination in the U.S., according to the EPA, but PFAS has shown up in trace amounts almost everywhere, from Arctic polar bears to Maine dairy farmers.

According to the EPA data, which is based on information collected by the U.S. Coast Guard’s National Response Center, 1,200 spills of firefighting foam containing toxic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as PFAS or forever chemicals, have occurred across the country since 1990.

Even trace amounts of some PFAS are considered a public health risk, according to federal regulators. High exposure over a long time can cause cancer. Exposure during critical life stages, such as in early childhood, can also cause life-changing harm.

(c)2024 the Portland Press Herald.

Visit the Portland Press Herald at www.pressherald.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.