()

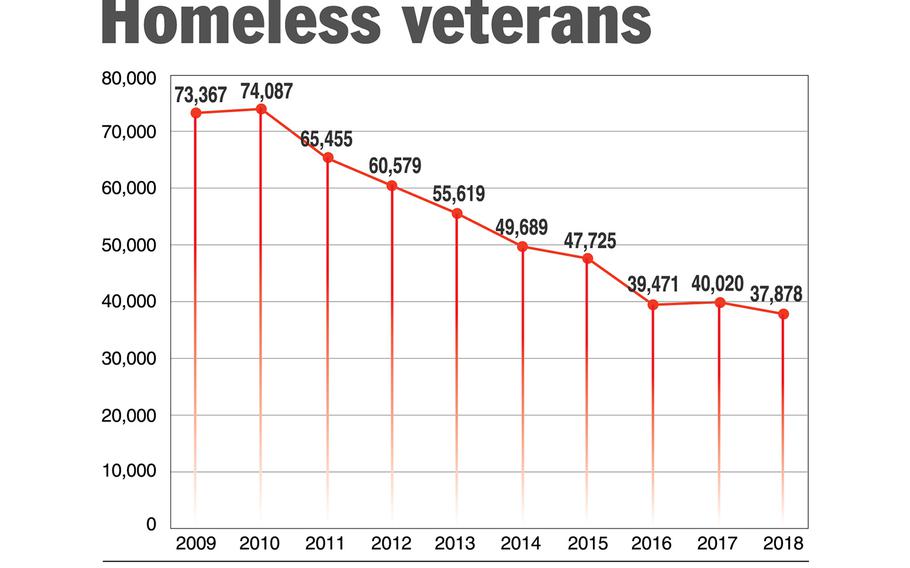

WASHINGTON — On the night of Jan. 24, 2018, volunteers across the country counted 37,878 veterans living on the streets or in transitional housing and shelters – a decrease of 2,142, or 5.4 percent, from those counted in January 2017.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development released Thursday the results of its annual point-in-time count of the country’s homeless. The decline in veteran homelessness comes one year after the department reported the first increase in veteran homelessness in a decade.

The number of homeless veterans declined in 34 states last year. For female veterans, homelessness went down by 10 percent, from 3,571 veterans counted in 2017 to 3,219 in January.

More than 4,000 veterans found homes in 2017 using the HUD-VASH program, in which veterans receive housing vouchers from HUD and case management and clinical services from the VA.

“The reduction in homelessness among veterans announced today shows that the strategies we are using to help the most vulnerable veterans become stably housed are working,” Department of Veterans Affairs Secretary Robert Wilkie said in a statement. “This is good news for all veterans.”

While HUD and the VA considered the reduction a win, Kathryn Monet, chief executive officer of the nonprofit National Coalition for Homeless Veterans, argued that national leaders aren’t giving enough attention to the issue.

“What we’re hearing from communities is that as homelessness fell off the secretary’s priority list with the change of [presidential] administration, it’s becoming more challenging to motivate people to do the work,” Monet said.

Former Department of Veterans Affairs Secretary Eric Shinseki established a goal in 2010 of ending veteran homelessness by 2015. The deadline came and went, but advocacy credited the initiative with boosting attention and resources that led to 36,209 fewer homeless veterans in the past eight years. Though VA leaders since Shinseki have said they’re committed to fixing the problem, advocates have become concerned the agency is letting up.

“Funding is going well; nothing has been taken away. People are still plowing away at evidenced-based practices,” Monet said. “But I think where communities are struggling is local and national leadership.”

In 2014, former First lady Michelle Obama and Dr. Jill Biden created the Mayors Challenge to End Veteran Homelessness. Through the program, 64 local communities and three states declared an effective end to veteran homelessness.

The qualifications to “end veteran homelessness” are based on a set of criteria from the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness. A key is being able to house veterans quickly. To achieve that designation, communities must find veterans permanent housing within 90 days after they’re identified as homeless.

Communities “sprint” to reach those standards, Monet said.

“They pull together all these people, have weekly meetings, and it’s a lot of hard work,” she said. “Once you get there, it’s hard to sustain that pace. Then to add on a lack of national leadership at the VA is discouraging, quite frankly, for a lot of them.”

California, particularly Los Angeles County, largely drove the increase in veteran homelessness from 2016 to 2017. This year, though, the county reported an 18 percent decline. Monet said there should be continued focus on large West Coast cities where there’s a lack of affordable housing.

“I think continued focus on some of these high-population areas is definitely a need – San Diego, Los Angeles, Seattle,” she said.

A state-by-state breakdown of the data is available at hudexchange.info.

Wentling.nikki@stripes.com Twitter: @nikkiwentling