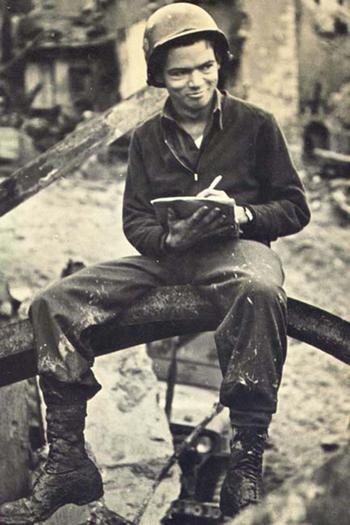

Bill Mauldin, a cartoonist famous for his gritty, yet still humorous depictions of World War II, as seen during the war. (Stars and Stripes)

Willie and Joe lie in their sleeping bags in the snow up against a log. "Remember that warm, soft mud last summer?" Willie says.

The pair of unshaven, weary grunts slogged their way from Italy to Germany in the pages of Stars and Stripes during World War II — along with their creator, Army Sgt. Bill Mauldin.

The mud-spattered, butt-smoking infantrymen illustrated the bleak and absurdly comic lives of them all. Mauldin's unsentimental work — teetering on the line between funny and tragic, unafraid to mock authority — spoke to and for front-line soldiers. They loved him for it. It's difficult to overstate how much.

As the war went on, Willie and Joe and other soldiers that Mauldin drew only got dirtier and wearier. In one 1944 cartoon, bedraggled, hollow-eyed soldiers trudge through a downpour with likewise pathetic prisoners, one with his arm in a sling.

"Fresh-spirited American troops, flushed with victory are bringing in thousands of hungry, ragged, battle weary prisoners," Mauldin's caption said.

That cinched his first Pulitzer Prize, at the age of 23.

Bill Mauldin, a cartoonist famous for his gritty, yet still humorous depictions of World War II, as seen during the war. (Stars and Stripes)

Mauldin, a westerner who went to art school in Chicago, joined the Army in 1940. In 1943, he waded ashore in Sicily with the 45th Infantry Division. By the end of a year of tedium interspersed with terror, almost all the men in Mauldin's rifle company had been killed, captured or wounded.

Mauldin's cartoons appeared first in the division newspaper, sometimes drawn using motor oil or wine. Initially a contributor to Stars and Stripes, he joined the staff in 1944, publishing six cartoons a week.

Gen. George C. Patton was not a fan. One of Mauldin's cartoons particularly incensed him: a Patton-esque general overlooking a beautiful vista and asking an aide, "Is there one for the enlisted men?"

Patton, who threatened to cease the paper's distribution within his Third Army, ordered Mauldin to his palatial Luxembourg headquarters to harangue him. "You know (expletive) well you're not drawing an accurate representation of the American soldier," Patton told him, as cited in his autobiography. "You make them look like (expletive) bums. No respect for the Army, the officers or themselves. You know as well as I do that you can't have an army without respect for officers. What are you trying to do — incite a (expletive) mutiny?"

Mauldin was unfazed. And by the end of the war he'd been awarded the Legion of Merit.

After the war, Mauldin continued his career as a cartoonist, made an unsuccessful bid for Congress, acted in movies, wrote books, made the cover of Time magazine and won a slew of prizes, including another Pulitzer.

He died in 2003 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Mauldin drew about 1,500 cartoons in his career. His favorite, he said, was one from the war years — of an old cavalry sergeant, grief-stricken, covering his eyes as he points his pistol at the radiator of his broken-down jeep. There is no caption.