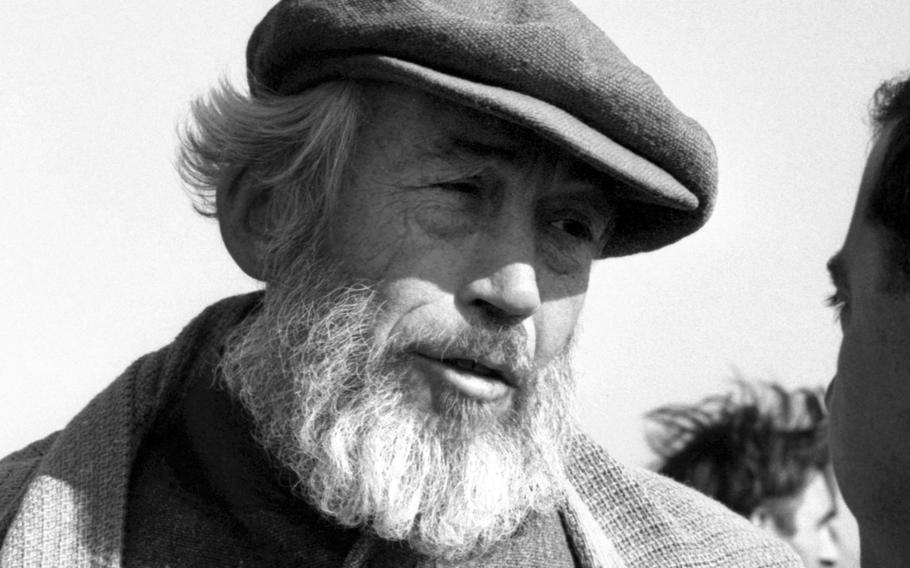

Director John Huston on the set of "The Bible" in Italy in 1964. (Gus Schuettler/Stars and Stripes)

THE CHILL was decidedly un-Italian as a thousand extras, actor Stephen Boyd, director John Huston, make-up experts, cameramen, assistants and a few placid buffalo gathered on the back lot of the Dino de Laurentiis studio outside Rome for the Tower of Babel sequence in the epic "The Bible."

The hundreds of extras coldly ignored the frantic pleas of the assistant director over the PA system; they had good reason as they were clad only in loincloths, and the weak Roman sun was failing to live up to advance ("fair and warmer") billing. The extras — "slaves" building the tower — jogged about, jumped up and down and beat their arms against their sides in an effort to get warm.

The "slave masters" were a bit better off; they were dressed in knee-length, burlap-like robes. "Priests" and members of the court suffered various degrees of chill; icy brass plates on bare chests numbed the "priests," and the thin gauze gowns of the court ladies did little to cut the cold wind.

Belgian Actress Claudie Lange, who came to Rome the summer of 1964 on vacation but stayed to become a star, draped a fur coat over her low-cut gown and tried to rub the goose bumps off her arms.

"I like acting, but I didn't know it was going to include polar expeditions," she said. Her mother clucked anxiously.

Actor Boyd, the "heavy" in "BenHur" and Nimrod in "The Bible," clutched his thick cloak about him and smoked a cigarette nervously. "I climbed those bloody stairs it must have been 14 times yesterday," he said, peering up at the 170-foot-tall plastic-and-wood-on-metal tower. "I thought my legs were going to drop off before we were finished."

The top of the tower, from which Boyd shoots his arrow at the heavens, was erected in Egypt, where Boyd and company spent a month or so in November shooting. Trick photography and process shots will match up the Egyptian tower top and Italian bottom.

Atop the tower, gaunt, 6-foot-4 director John ("Maltese Falcon," "Freud") Huston, nattily attired in a cloth cap, tweed jacket buttoned to the neck, black leather trousers and a lavender knee-length woolen shawl, rested his magnificently bearded chin in his hand and observed, "A director's job at this point consists of mostly just waiting around."

Huston, making his first stab at biblical epics with this $18 million production, crouched down to watch as the Italian assistant director called for places. At the cry of "Avanti!" slaves began slaving, masters mastering and actors acting. Buffaloes pulled sledges loaded with stone and brick, and the camera ground away.

BOYD, his face frozen in a mask with gold-painted eyebrows and heavy mascara, mounted the stairs again, followed by his queen, bow-bearer and court. Slaves fell on their faces as he passed — a risky thing on the narrow and curving stairway.

Boyd & Co. wound their way past the prostrate slaves, past the Dimension-150 camera ("bigger and better than Cinerama!") and out of view of the lens. Cloaks, sweaters and mink were immediately produced; the assistant director called "Cut!" and hundreds of extras scurried for their coats.

Boyd lighted a cigarette again as a make-up man went over his gilt. "I'm off for Hollywood tomorrow where I'm to do 'Fantastic Voyage' for Columbia,"' he said.

"You know, when they offered me this role I wasn't sure that I wanted to take it. I didn't need the money, and I had planned on a short vacation between films. But a chance to work with Huston decided me, and now I'm glad I've done it despite the tight schedule."

Later, a De Laurentiis soundman will fly to Hollywood with prints of Boyd's sequence for dubbing. In these days of high production costs and international actors, producers have to follow the stars and add the words wherever they can catch them.

"You know," said Boyd, now a Hollywood resident, "Huston became an Irish citizen not too long ago — the same week I became an American citizen. I'm not sure which country made the best of the trade."

Then Huston loped over, his shawl trailing behind him, upset about a camera angle.

"Let's shoot it again, only try to get more of those brick kilns down below in the picture," he said in his soft melodious new-Irish baritone. The cameraman shrugged, gave his orders and looked about with Huston for a better angle.

Angle found, he ordered the cameras moved; this proved to be a tricky business, so Huston suggested a break, and actors and extras searched for cover from the wind.

The new angle included a part of the back lot not covered by specially imported yellow sand to match the Egyptian desert shots, so a hurry-up call went out to the prop men for more sand. While the sand was being spread, Huston hunkered down by the railing and looked around him.

"This is a hell of a business," he said, pausing as a series of coughs bent him double. "Caught this cough in Egypt; broiling in the day, freezing at night. I almost coughed myself out of a camel saddle down there."

THE ROAR of a lion split the air, coming from the menagerie De Laurentiis has gathered for the Noah's Ark sequence, in which Huston will portray the biblical boatbuilder.

"What a mess it's going to be, marching those animals into the Ark," Huston said, gesturing toward the animal cages a half-mile away. "I'll probably get chewed up by a tiger. Biggest ones I've ever seen over there.

"They're Siberian tigers we're using. I've shot Bengal, and these are much bigger. Look like they'd polish you off for a snack before lunch. Don't know how we're going to get them to walk up that gangplank. Got an Austrian trainer; he came with the circus they bought. But he can't turn his back on those cats or they'll tear each other to pieces."

As Noah, in later shooting, Huston not only appeared before the camera but also had to run behind it to check on angles and sequences. It didn't bother him a bit.

"It's easier to work with animals than humans — they never make mistakes," he said, slapping one of the elephants in the ark built in the new Di Laurentiis sound stage, the world's biggest. Some 1,000 birds fluttered wildly about the three-deck, 150-foot long and 68-foot high ark set, their multicolored feathers gleaming in the bright lights.

All the stagehands, grips and. make-up crew were wearing raincoats and rain hats to protect themselves from the "rain" dropped by the birds flying about the ark. The actors had to fend for themselves in the midst of the deluge; some huddled under light stands, while others just stood and took the torrent.

Like the actors playing Noah's sons Japeth, Shem and Ham .and their wives, and Mrs. Noah, played by Neapolitan actress Pupella Maggio, Huston was dressed in simple burlap-like robes and sandals. The hippos, giraffe, water buffalo, seals and honey bears were happily snorting away in the thick straw.

In special glassed-in cages (with plate glass capable of withstanding 2,500 pounds of pressure) were the ferocious lions, tigers and bears. Special walkways had been built into the ark from outside steel cages for the flesh-eaters, so that they would never be able to mix with the "free meal" animals.

The massive ark "zoo" is far from a free meal for producer De Laurentiis. Feed and care of the beasts costs a hefty $6,000 a day, with 1,320 pounds of hay, 550 pounds of meat, and 440 pounds of oats, 330 pounds of vegetables and various other snacks, including 5 pounds of honey, making up the daily menu.

And all the 200 animals and half of the 1,000 birds have to be moved out of the ark at night and back in at dawning; the lack of fresh air and sunlight could be fatal to the wilder animals. Also, the elephants and camels must be walked between scenes; otherwise they become restless.

Just about the saddest case of all are the giraffes. The knock-kneed, long-legged beasts somehow can't be persuaded to walk into the ark; they have to be lifted into place with a crane.

Most at home among the bellows and barkings is Huston, a veteran big game hunter and rider to the hounds. As he chatted with some of the actors, he slapped one elephant under the front leg, bending his back into the effort. Then he stopped and started to walk away; the elephant gently but firmly reached out with his trunk and grabbed Huston by the arm and pulled him back, mutely pleading for "more."

"Didn't teach him that; he really likes to get battered around," Huston chuckled. "You know, I get along with the other actors in this sequence very well; most of them are animals, and we went to the same acting school.

"My only trouble is with the red-tailed baboon. Every time we start a scene he bends over and sticks his rear into the camera. I consider that highly unprofessional," Huston said.

HUSTON said that he wasn't taking his acting chores "too seriously," despite the praise he won from critics for his role in "The Cardinal."

"If I'm going to do anything other than directing, I'd like to write," he said. Writing, he said, is "relaxing to me. I dashed off a one-act play the other night when I couldn't sleep — purely. for my own amusement."

The Ark sequence is the last major part of "The Bible," which covers the events of Genesis from the Creation through the Garden of Eden and including the Sacrifice of Abraham.

Any difficulties in shooting the nude scenes in the garden?

"No-o-o-o," drawled Huston. "We just had to be careful not to give the kiddies a lesson in anatomy across a 150-foot screen."

A commissary man came up handing out cups of hot bouillon. Huston took one and sipped at it appreciatively. "Might be better with a bit of Irish in it," he said wistfully.

Then the camera was in its new place, and Huston walked over to look over the new setup.

"That's fine," he said, peering about the massive camera and giant fill light. "Now, Stephen, when you come up to this stairway, swing on your left foot and then look back at the slaves and your wife."

Boyd, all business in his fantastic robe and make-up, walked up to the stairway and ran through the action a couple of times while the cameramen worked out focus changes. "OK?" he then asked Huston, who nodded. The royal procession got in place, the slaves fell to their faces and the camera whirred.

Huston walked around the tower, out of the action. "Not much for me to do there now," he said. He leaned against the plastic brick-facing on the tower and looked off at the distant blue Tyrrhenian Sea.

"Been in this business for a long, long time — since 1935 when I worked for Warners as a writer. 'Maltese Falcon' was my first own film — I wrote it and directed. Met a lot of fine people in films.

"Humphrey Bogart was one of the finest. He was one of those rare instances when a man comes through on screen as big as he was in life. He was a close personal friend. ... Hated it when he died."

Huston said he "liked 'em all" when discussing his films, but he had a special fondness for some.

"Now, `The Red Badge of Courage' I liked very much," he said judiciously. The film was a critical success but lost money. It was also the subject of a series of articles in The New Yorker by Lillian Ross, which touched off a storm of anger among Hollywood figures who felt they had been unfairly caricatured and betrayed.

"Why, I enjoyed the book" (the pieces were later published as a book)," Huston said, "but most of the others were sore as hell. I don't think they understood it, just like the people who were so upset when she did a piece on Ernest Hemingway.

"Hell, Hemingway liked it. And I liked what she said about `Courage.' "

Does Huston see many of his old films, such as "Falcon" or "The Treasure of Sierra Madre," which won him two (directing and writing) Academy Awards?

"No, I don't get much of a chance to see them again. Much of the time when I have a chance I'm in a country where they dub the sound, and I don't want to see a film distorted that way."

Boyd, who had finished the scene and was waiting for a retake, commented on film people viewing their own movies.

"When a reporter writes a story and turns it in, it often gets changed by the city editor, the news editor or the copy editor. So a reporter can get something out of seeing his story in final form.

"But an actor, or a director, goes over a scene time after time until he has it down letter perfect. So there's almost no interest in going to see it six months or six years later," he said.

"It's funny about some of those old films," Huston said. "Take `Asphalt Jungle,' Marilyn Monroe's first film which I directed. It got a cold reception from the critics, but now it plays the art circuit regularly and is almost a classic. Same goes with `Courage' and `Beat the Devil.' "

Then the assistant director called and Boyd began the scene again ("It'll be 15 times up those stairs today," Nimrod predicted darkly.) Huston walked to the edge of the tower platform and stared moodily at the massive Ark.

"Boy, I bet those tigers chew somebody up over there when we get started with the animals," he said, shaking his head. "Oh, well, that's next month," and he strolled happily back to the current action.