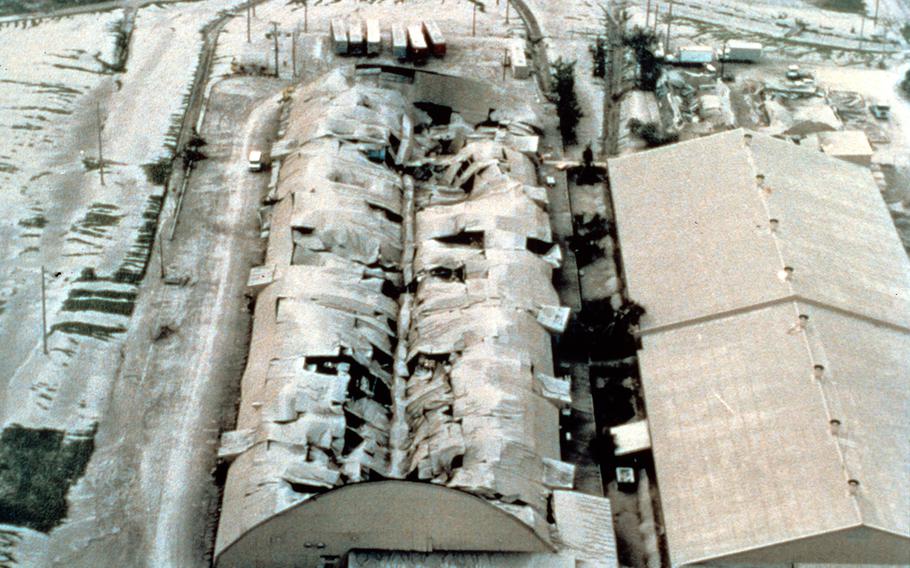

Mount Pinatubo, Philippines. Aerial view of collapsed warehouse, Clark Air Base. (R. Batalon)

ANGELES CITY, Philippines — In late August 1991, Joseph Snodgrass pulled a brazen jail break from his cell on Clark Air Base. Awaiting trial for conspiring to murder his wife eight months earlier, the hulking Air Force sergeant feigned illness, jumped a guard and held a butter knife to his throat.

Once outside, the fugitive jumped into a car and sped away to — well, that was the problem. To where?

Two months earlier, nearby Mt. Pinatubo had blown its top, layering Clark, Naval Base Subic Bay and miles of countryside with thick, rain-soaked volcanic ash.

The gray goop still coated much of the landscape. Buildings had collapsed. Trees bent and broke under the sludgy ash, deforming them into what one eyewitness described as something in a Dr. Seuss book.

Snodgrass couldn’t get his bearings.

“He drove through the ash for a while and didn’t know what to do, and then finally the security police zeroed in on him and he said, ‘Put me back in jail,’” recalled Mark Hanneman, the Air Force OSI agent in charge of the case.

Volcanic disorientation, however, reached all the way to Washington, D.C. The eruption’s aftermath ultimately triggered the decision to withdraw all American forces from the Philippines and to close Clark and Subic. The last U.S. troops and ship pulled out of that naval base more than 20 years ago.

Still, as final as that departure seemed, U.S. naval ships now routinely dock at Subic, and the Philippines government has made it clear that it welcomes more of the same.

For those there during the “last days” of Clark and Subic, it was an era of danger, easy living and camaraderie. The end was sudden and unexpected.

“To me, Clark Air Base and the Philippines — from a mission perspective — was like being in Tombstone or Dodge City,” Hanneman said. He was transferred to Clark in January 1989 as part of a counterterrorism team investigating the murders of servicemembers by the Communist group New People’s Army.

The NPA’s assassination “Sparrow Squads” crowned a spate of killings early that year with the shooting deaths of two airmen from Kunsan Air Base in South Korea who were at Clark for a training exercise.

The base command thereafter restricted airmen’s movements off base to a small area nicknamed “The Fish” for its curved boundary.

“We were allowed access to only one part of the town,” said Lauren Sobkoviak, a tech sergeant who worked in Clark’s public affairs office at the time. “There was a lot of stuff going on that made people a little nervous, a little claustrophobic, would be a good way to put it.

“Nobody really expressed it, but you could feel it in the air.”

For example, there was the call he took from an airman’s wife asking him to confirm whether terrorists were attacking the base and storming across the runway.

“At the time, the gates were closed because of a possible terrorist threat,” he said. “That always put everyone on edge, especially after two guys getting killed.”

Adding to the overall anxiety were the beleaguered negotiations between the Philippines and U.S. governments about renewing the base leases, set to expire in 1991.

Many Filipinos thought that the U.S. should pay considerably more for using the bases, a mindset heightened by a growing wave of nationalism at the time.

Even after six rounds of negotiations, the two countries were far from reaching an agreement on price, according to the book “The Ash Warriors,” a history of the Clark evacuation and closure by C. R. Anderegg, a vice commander at Clark during that time.

The Philippines wanted $825 million per year for seven years, but the U.S. wouldn’t budge from $360 million per year for 10 years, Anderegg wrote.

What Philippines negotiators couldn’t guess at the time, however, was how doomed a base deal truly was because the George H. W. Bush administration was prepared to abandon it. Richard Armitage, the U.S. negotiator appointed by Bush, told Anderegg in an interview that he was told “do your best, but we don’t care.”

When Pinatubo blew on June 15, 1991, it was the second largest eruption in the 20th century, but it went from dormant to deadly in an amazingly short time.

Troops at Clark first noticed what looked like white smoke rising from the mountain just three months earlier.

“We got our first dusting of ash at the end of May, that rotten-egg smell from the volcano,” said Sobkoviak, who had worked near Mount St. Helens in Washington when it erupted in 1980 and was one of the few airmen who’d had first-hand experience with a volcano.

Behind the scenes, the top commanders at Clark were grilling the volcanologists from the U.S. Geological Survey who’d come to monitor Pinatubo. The officers “wanted to make evacuation plans and give it to the population and calm their fears,” Sobkoviak said. But the scientists, whom Sobkoviak had helped set up video monitors on the mountainside, said it wasn’t possible to predict the time of eruption.

Political implications of evacuation also loomed.

“A premature evacuation of the base might be interpreted as a signal that the Americans were trying to bully the Philippine Senate by showing them how bad the economy might become without Americans spending their dollars there,” Anderegg wrote.

Eruption seemed imminent on June 10. And so began the transfer of roughly 15,000 dependents and non-essential servicemembers from Clark to Subic, about 23 miles south of Pinatubo. Most drove their own vehicles.

Some of the refugees were taken in by naval families. Hanneman said that he and his fellow OSI members were housed by their naval counterparts with NCIS at Subic.

For many others, though, the transfer was all about “confusion and disorganization,” Anderegg wrote.

Raymond Jones, a tech sergeant who worked in communications, drove the caravan-style sojourn in his car with his wife and 3-year-old son.

“We were told to park in a field and line up outside one of the open messes there,” Jones recalled. “I waited in line with a number for five or six hours to get a place to stay for the night.” They didn’t get one.

The family settled down to sleep in the car when they heard a rap on the car door. “It was a Navy policeman who invited me and my family to his house to spend the night. What a godsend!”

About 2,000 airmen remained at Clark, mostly security police.

Pinatubo erupted about 6 a.m. June 15, ash and smoke rising more than 20 miles. The mount’s top 900 feet disintegrated.

Sobkoviak, sound asleep after working a night shift, was awakened by his portable radio blaring: “Evacuate! Evacuate! Evacuate!”

As planned, he and the remaining airmen drove their own cars to a college campus about 15 miles west.

Exhausted after arriving, he lay down on a balcony floor after placing a cloth over his face to shield him from ash. “I wasn’t asleep more than an hour, and I woke up gagging because I wasn’t getting any air because there was so much ash on my face,” he said.

Hanneman recalled holing up in his host’s house for a day and night of “raining rock and ash,” earthquakes and claps of thunder. “I’ll never forget the next morning,” he said. “There was deafening silence. We’re in the jungle, a tropical setting with bugs and birds and screeches, but it was just silent.” Sobkoviak returned to Clark five days later. He was stunned.

“This is the honest god’s truth: when I got back on base I had no idea where I was. I mean, it’s hard to explain — I knew where I was but I couldn’t pinpoint where I was.”

He saw lahars, which are volcanic mudflows, as deep as 18 feet on base. New cars for sale at the base PX had been stacked atop each other by one lahar.

Ash soaked by monsoon rain clung to everything and had seeped into many buildings. Of the roughly 3,500 buildings, more than 100 had collapsed and twice that many had serious damage.

“My initial impression after looking around at the damage was that if we don’t close the base it will cost a hell of a lot to repair it,” he said.

It didn’t take long for the Pentagon to conclude the same, and an agreement was reached that the U.S would turn Clark over in 1992 but continue to lease Subic for another 10 years. The Philippine senate failed to ratify the agreement, though, setting in motion the closure of Subic a year later.

In fact, the transfer of troops and dependents out of the Philippines had begun days before the eruption as part of Operation Fiery Vigil, a massive transfer of 20,000 souls from Subic to the southern island of Cebu and then to the U.S.

Jones and family rode a frigate to Cebu.

“The ship was packed, and we slept on the floor of some kind of electrical room, but there was no problem sleeping after what we’d been through,” Jones said. They sat for more hours in the tropical sun after their landing craft got stuck on a reef outside the Cebu port.

Only later did he learn that their off-base home had been looted.

Thomas Utts, the author of “GI Joe Doesn’t Live Here Anymore,” a history of the base, recalled that one airman tried to bring a canister of volcanic ash back to the U.S. as a souvenir but had it confiscated as contraband.

“But he’d left his car in Subic, and when it arrived in the states it was filled with more ash than he had any need for,” Utts said with a laugh.

Hanneman remained at Clark into October, overseeing the case against Snodgrass, who was eventually convicted and given a life sentence.

Sobkoviak was among the very last to leave the base shortly before it was turned over in November 1991. Riding a bus with other airmen bound for the Manila airport, he watched the landscape change from “the surface of the moon” to “civilized, I guess is the word,” he said.

“I’d been there on borrowed time, and I made the most of it. I knew I was going to go out with a blast.”