U.S. Army Europe Gen. Frederick Kroesen and his wife, Rowena, were being driven to the dentist in Heidelberg when their armor-plated car was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade in Sept. 1981. The couple received minor injuries. (Stars and Stripes file photo)

One spring day in 1972, V Corps barracks in Frankfurt was bombed, killing one American officer and injuring 13.

Two weeks later, two car bombs exploded inside U.S. Army Headquarters’ Campbell Barracks. Three U.S. soldiers died in the blasts and five were wounded.

Fourteen people were hurt when Rhein-Main Air Base was bombed in August 1981. When it was bombed again in 1985, two people were killed. Another person, Spc. Edward Pimental, had been murdered the night before for his identification card and the access to the base it provided.

U.S. soldiers and airmen stationed in Germany were repeatedly terrorist targets in the 1970s through the mid-1980s. Scores were wounded — although the death toll was fewer than 10 — in a series of a bombings spread over a decade.

Even the Army’s top general in Europe wasn’t immune. Gen. Frederick Kroesen, U.S. Army Europe commander, and his wife could have been killed in September 1981 when their armor-plated Mercedes was hit by a rocket- propelled grenade and automatic rifle fire as they motored along a Heidelberg street on the way to the dentist.

“I remember looking at my husband and seeing the blood run down his neck,” said Rowena Kroesen, in a phone interview from her home in Alexandria, Va., where she and her husband are retired.

The two were taken to the hospital, where bits of glass were removed from their skin and clothes. Then her husband went to Fulda to give a talk.

“And I went on to the dentist,” she said.

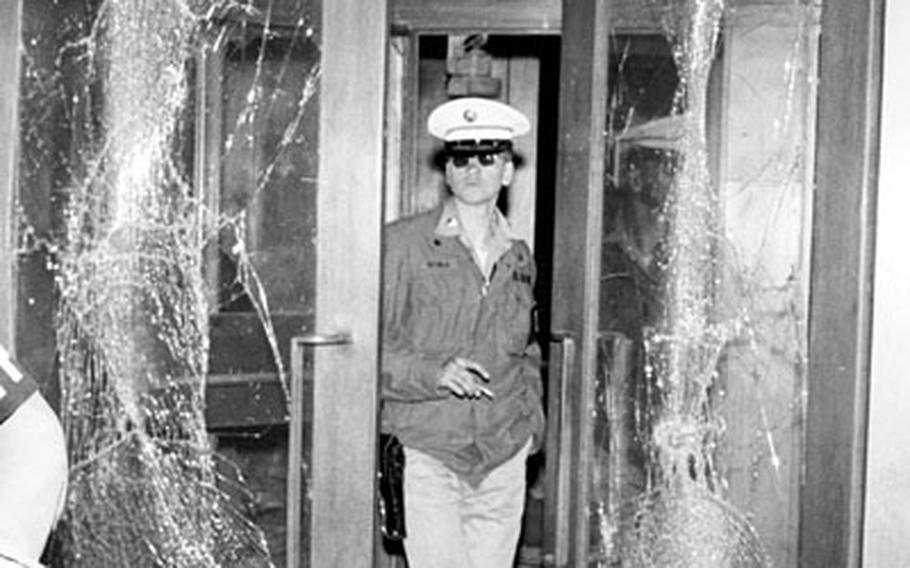

An Army officer was killed and 13 persons injured when bombs went off at V Corps headquarters in Frankfurt, Germany on May 11, 1972. A military policeman stands between the shattered glass doors at the entrance of the headquarters building. (Stars and Stripes file photo)

The terrorists of that time were German, primarily a group of former students, journalists and intellectuals called the Baader-Meinhof Gang, also known as the Red Army Faction. They, along with the Red Brigades in Italy, espoused an anti-imperialist, antiwar, anti-capitalist ethos, and sought to kill German politicians and industrialists, as well as striking U.S. interests.

“They staged some fairly spectacular bombings,” said Andy Morris, one of three U.S. Army Europe historians. “But it had no long-term impact.”

But there was no “war on terror” then.

“It was a strictly law-and-order operation,” Morris said.

At least in retrospect, the psychological impact, such as the death toll, seems to have been less severe than the fear from the current wave of ruthless terrorist bombings of civilians.

“We may have had some wives who were leery but everybody still went everywhere and did everything,” Kroesen recalled. “There were so many incidents. We just lived with it.”

Despite the threat, increased security measures at American bases were fleeting. Bruce Siemon, another USAREUR historian, said after the second Rhein- Main bombing, checks were put in place at the base gates that created long lines in the mornings.

“That lasted a couple of weeks,” he said.

Over the ensuing decade, with repeated terrorist bombings on a far bigger scale, resulting in growing numbers of people killed, things changed.

The terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, “changed our perception of what the enemy was capable of doing,” said USAREUR historian Kevin McKedy.

Daniel Keohane, a terrorism expert at the Centre for European Reform in London, said he saw significant differences between the Red Army Faction and today’s radical Islamist militants, in ideology, tactics and weaponry.

“The amount and the number of bombs are on a greater scale than any European group has ever used,” he said.

Rowena Kroesen did not emerge unscathed from her brush with terror, despite what seemed to be minor injuries. The explosion left her with tinnitus, or ringing in the ears, that she still deals with, she said. And she remembers that hours after the attack, after she turned out the lights to go to sleep, her nonchalance had vanished.

“I started to shake,” she said.

She lay in bed, involuntarily shaking away, until her husband noticed. The general told her she’d be OK.

“He said, ‘Don’t worry. It’s your first time to be fired on.’”