Young fairy fans brought their wings to last year’s first annual Fairy Tales event on the South Mountain Fairy Trail in Millburn, N.J. The next event, which features fairy stories, face-painting and walking tours, will be May 4. (Beth Kelly)

Therese Ojibway was hiking in the woods when she came across a couple of tree twigs naturally entwined together like a tiny fairy swing.

It reminded her of miniature fairy furniture she’d fashioned as a child in her backyard, and right away she thought of her son, Clinton Craig, who was diagnosed with autism at age 2.

Mother and son would go on frequent hikes around the 2,110-acre South Mountain Reservation in Millburn, N.J., to get some exercise and go exploring, she said. Craig, who was 10 at the time, felt happy and free in nature.

Clinton Craig and his mom, Therese Ojibway, on the South Mountain Fairy Trail in 2016. Therese started making fairy houses for Craig, who has autism, to find on their frequent hikes around the 2,110-acre South Mountain Reservation in Millburn, N.J. Craig, who was 10 at the time, felt happy and free in nature. (Therese Ojibway)

“I thought it would be fun to leave him a few little surprises,” Ojibway said.

She fashioned a wee sofa out of dead tree bark she’d found on the ground, added a few moss cushions and tucked it inside a tree hollow. Her son discovered it and was delighted.

“Over the next several months, I started slowly adding to it, using natural materials from the environment to make fairy houses,” said Ojibway, 68.

As the teeny wonderland grew, she figured she should tell someone at South Mountain Reservation what she was doing.

So in 2011, she approached the volunteer group South Mountain Conservancy, which looks after the nature reservation’s trails for Essex County Parks. Organizers said she was fine to continue making her enchanted forest, as long as the fairy houses were confined to a half-mile section at the beginning of the Rahway River Trail, she said.

Volunteers even began contributing mini whimsical items to the fairyland.

Thirteen years later, there are more than 80 wee fairy dwellings built by both Ojibway and volunteers, tucked inside trees and root systems along what it now known as the South Mountain Fairy Trail.

When Ojibway’s husband died in 2022 and she and her son decided to move to Michigan to be near family, she said she worried whether anyone would want to take over as the fairy trail’s keeper. It had become a destination for people near and far.

“I was sad to leave because the trail had become such an important part of the community,” she said.

Ojibway was overjoyed when two women immediately raised their hands offering to be the keepers of the trail.

Julie Gould and Beth Kelly took over stewardship of Ojibway’s enchanting fairyland almost two years ago, enlisting Scout troops and students to help with the upkeep. They do weekly inspections to tidy the trail, replace any caved-in structures and repair worn moss roofs and broken chairs.

Beth Kelly and Julie Gould on the South Mountain Trail last year. They took over looking after the trail when the founder, Therese Ojibway, moved in 2022. (Julie Gould)

They are now preparing for spring hikers, creating new fairy houses and furniture to replace anything that may have been vandalized or damaged over the winter by snow and ice.

“I’m really proud to continue Therese’s legacy, because it helps draw more kids to the woods,” said Kelly, 63. “We want to keep the magic going.”

On May 4, she and Gould will hold their second annual free “Fairy Tales at the Fairy Trail” event featuring fairy stories, face-painting and walking tours.

“Ever since I discovered the trail during the pandemic with my two little boys, I’ve wanted to be a part of it,” said Gould, 39.

“It’s not just that I get to be in the woods every week,” she said. “It’s about seeing the excitement in the kids’ eyes as they peer inside the houses and look for fairies. This trail nurtures their imaginations.”

When Ojibway first started leaving tiny moss-and-twig houses in the forest, she said some people were critical and wondered why looking at a natural landscape wasn’t enough of a reward for children and their parents.

“I had a few people say they were going to go tear everything out — that it didn’t belong there,” she said.

“My response was that the fairy houses were bringing families here who might not otherwise come,” Ojibway said, noting that the nature preserve is about 20 miles from New York City. She shared the story of how she started the trail with Patch.com.

“A lot of the kids who come are city kids,” she said. “Once they explore the fairy trail, maybe they’ll go off and explore some of the other trails. There is a place here for a small bit of magic.”

Children don’t spend enough time outside and benefit when they explore natural environments, according to the National Institutes of Health. Time outdoors helps kids become more creative and confident, but people of all ages are boosted by short breaks in nature.

“A lot of people don’t get enough interaction with nature, and the fairy trail gets kids thinking about what it means to be in a forest,” said Dennis Percher, chair of the South Mountain Conservancy’s board of trustees.

“Anything to make them feel more comfortable in the woods is a positive thing,” he said.

Kelly and Gould wear green T-shirts identifying themselves as “Fairy Trail Keepers” whenever they conduct trail cleanups or do repairs to the fairy houses tucked in nooks along the pathway.

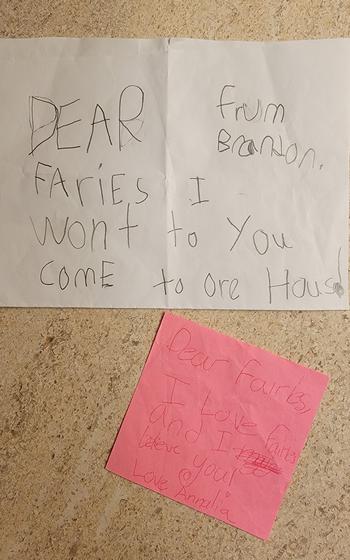

“Kids will ask if we’ve seen the fairies, and they’ll leave little notes for them in the houses,” Gould said. “Usually they’ll say something like, ‘Dear fairies — please come and visit me at my house.’”

Children often leave notes inside the fairy houses, said Julie Gould, one of the keepers of the South Mountain Fairy Trail in Millburn, N.J. (Julie Gould)

“The fairy trail grabs their imaginations,” Kelly added. “We’ll talk about what they think fairies do all day. Do they like to take rides on the leaves? That sparks a desire for them to go exploring and look for fairies.”

Ojibway said she’s happy to know her Thumbelina-sized creations are still captivating young hikers and their parents. She and Craig, now 33, plan to return to the fairy trail sometime this summer for a visit, she said.

“I imagine that some of the little houses I made will have gone back to nature, and that’s how it should be,” she said. “You gather up the pieces, and you make a new one. That’s part of the fairy magic.”