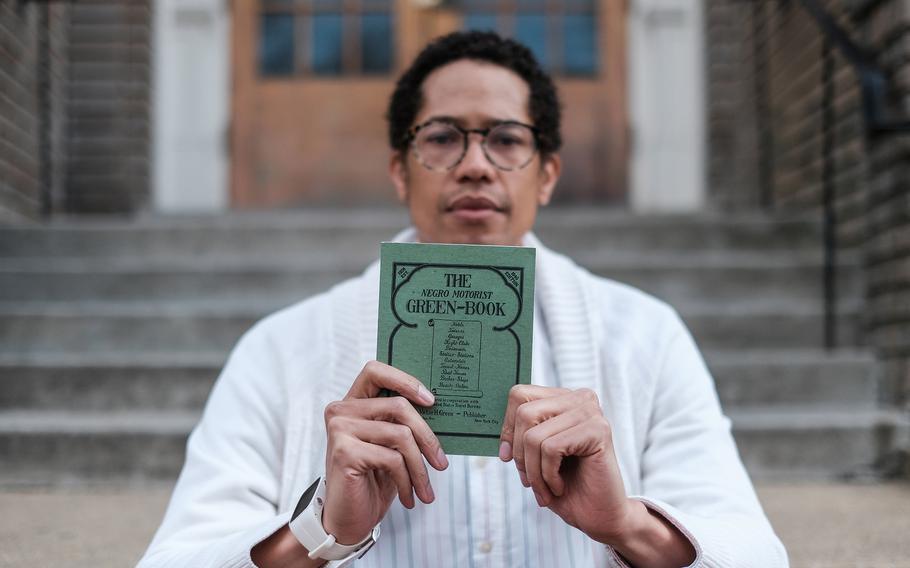

The writer holds a reprint of the 1940 Green Book. (Michael A. McCoy/For The Washington Post)

Like most, I depend on my smartphone to help me get from point A to point B. As a historian, my maps have more meaning.

Along with official points of interest and landmarks, my maps are accented with sites that often don’t have historical markers or plaques. When combing through archival materials or watching a documentary, I note addresses where historical figures lived, correspondence was sent and meetings were held. Even for far-off places that I have no plans to visit, I mark these locations on maps, not certain where life will take me someday.

When these sites relate to African Americans, they often lead me to what was once “the Black Belt” or “across-the-tracks.” These phrases, used to describe sections of cities and towns where racial segregation cordoned off Black life, often do not describe the trendy neighborhoods of today. In many cases, traces of what once existed have been erased or are unrecognizable.

Given my love of history and affinity for maps, it was no surprise that someone gave me a reprint of the 1940 edition of the “The Negro Motorist Green Book.”

First published by New York postal worker Victor H. Green in 1936, the annual travel guide for African Americans printed until 1966 listed gas stations, restaurants, bars and private homes owned by or hospitable to Black patrons. These listings, organized by state, D.C. and later with international additions, tell the story of how segregation and sundown towns affected intrastate and cross-country travel for African Americans.

Immediately after receiving the Green Book, I knew it would accompany me on my own trips. But with no travel plans on the horizon, I turned to the sites in my rapidly changing home base - the D.C. area.

University Garage

Williams Alley NW

The first address that caught my attention was one that I knew well. For the past few years, I have been tracking the progress of a building in a Columbia Heights alley being converted into private residences. My curiosity kept me taking pictures of the construction as if it were a seedling in a cup, but I hadn’t turned to any newspapers or city directories to learn more about what appeared to be a small warehouse.

The University Garage, once a parking place for Black travelers in the Columbia Heights area of Northwest Washington, is now a condo building. (Michael A. McCoy/For The Washington Post)

In the Green Book, I learned that what appeared to me to be a warehouse was once a garage where Black travelers could park their cars, a necessary cog in long-distance travel. The building is listed in the Green Book as the University Garage - near Harvard Street and Columbia Road.

The alley was named Williams Alley in 2017 after community leader Theodore Williams.

Republic Gardens

1355 U St. NW

A location in the Green Book that I immediately recognized was Republic Gardens.

In 1894, 1355 U St. NW was constructed as a “dwelling,” but by the 1920s, U Street was becoming alive with jazz clubs, restaurants, theaters and movie houses. Black Broadway would become the crown jewel of Black Washington, and this residence turned nightclub would hold a pivotal place in U Street’s renaissance. It was a stage for performers such as Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker and Ella Fitzgerald.

Sadly, the second half of the 20th century spelled the end for many sites of U Street’s glory days, including Republic Gardens. Racial desegregation in the 1950s removed many of the limitations that had confined a burgeoning Black population to the greater U Street corridor. In 1968, after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis, frustrated and impoverished citizens protested, which led the deployment of the National Guard in the city. This turbulence set off a period of disinvestment in U Street.

After closing and standing vacant for years, the historic nightclub was reborn in the mid-1990s. This carried Republic Gardens’ name and tradition into the 2000s as investment in U Street returned and gentrification began to take hold.

After another closure and period of vacancy, the space became Elements nightclub in 2021, where partyers on the roof can look over a very different D.C.

The Johnson Hotel

1502 13th Street NW

In the 1940 Green Book, there are seven listings under hotels in D.C. Of the seven, only four buildings remain: the Whitelaw, the YMCA, the YWCA and the Johnson Hotel in Logan Circle.

The Johnson Hotel is now a condominium building in the Logan Circle area of Northwest Washington. (Michael A. McCoy/For The Washington Post)

Today, the tree-lined streets and the charming architecture around Logan Circle make this one of D.C.’s most desirable neighborhoods. The Johnson Hotel was at 1502 13th St. NW and was a stately mansion originally built for retired Navy Lt. Cmdr. Seth Phelps. Now, it is home to $500,000-plus condos.

To better understand the Johnson Hotel’s history, I first needed to determine whether it was a “touring home” or an actual hotel. I turned to the D.C. city directory for 1939. There, I found a listing for Jos M. Johnson and the Johnson Hotel.

With this information, I searched the digitized archives of the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper for any mention from notable guests or even an advertisement, but that turned up nothing. This led me to suspect that the Johnson Hotel was a smaller outfit.

The 1940 Census told me that Joseph Johnson, listed as Joe M., was 45 years old on April 22, 1940, when a census taker visited 1502 13th Street NW. He was unmarried and the only full-time resident of the address, and his occupation was “General Manager” of a “Lodging House.” Of his 80 Logan Circle neighbors, four were White. Most of his neighbors identified as African American. Segregation and an increasing African American population in D.C. shifted the profile of this neighborhood not far from the U Street Corridor.

This change in the neighborhood and for mansions like this one is described in the Logan Circle Heritage Trail’s walking tour and booklet, “A Fitting Tribute.” “With U Street’s ‘Black Broadway’ so close, and segregation barring African Americans from white-owned hotels, entrepreneurs converted large houses into lodgings for black travelers,” it says.

Standing before the building recently, I wondered whether any of the current residents knew of this history and whether it had any meaning to them.

S.W. Keys restaurant

1853 7th St. NW

Although U Street is an unmatched place in D.C.’s Black history, nearby Seventh Street was immortalized in Jean Toomer’s “Cane” and in the Langston Hughes autobiography “The Big Sea.”

Mesobe Deli Market, right, now occupies the space of S.W. Keys on Seventh Street NW. (Michael A. McCoy/For The Washington Post)

Around the corner from the illustrious Howard Theatre and in the shadow of the Southern Aid Building, the oldest Black life-insurance company in the country, was S.W. Key’s - just listed as “Key’s” in the Green Book - a restaurant that served as a destination for Black travelers.

The 1940 edition of the Green Book lists Key’s at “7th & T,” one of only two D.C. restaurants in the guide, both on Seventh Street. With only cross streets, I needed to find out where exactly Key’s was, so I turned to the city directory, the precursor to the yellow phone books. Along with the home address of Samuel and Louise Keys, there is a restaurant listed at 1853 Seventh St. NW.

From the photograph, S.W. Keys looks like the perfect place to enjoy a meal before a swinging show at the Howard Theatre or for those recently arrived in town who were navigating the color line. The same one Hughes, reflecting on his time in Washington, captured in his autobiography: “I could not get a cup of coffee on a cold day anywhere within sight of the Capitol, because no ‘white’ restaurant would serve a Negro.”

Today, the Key’s space is occupied by Mesobe Deli and Market, a modest carryout spot. There is even a large picture of Samuel Keys’ restaurant from 1940 on the neighborhood-heritage-tour sign in front of the Southern Aid Building.

The Whitelaw Hotel

1839 13th St. NW

One block south of U Street and a block east of 14th Street is an affordable-housing complex that once was the Whitelaw Hotel, which opened in 1919. The building at 13th and T streets NW is a favorite of mine for many reasons. Its beauty, courtesy of the architect Isaiah T. Hatton, is timeless.

The Whitelaw Hotel is now an affordable-housing apartment building. (Michael A. McCoy/For The Washington Post)

Hatton, a Maryland-born African American, left a legacy of buildings near the Whitelaw. These buildings, including the Southern Aid Society Building on Seventh Street and the Industrial Bank on U Street, demonstrate the vibrancy of the community as well as how segregation kept Hatton’s talents from moving beyond Black Washington.

The hotel-apartment building was the brainchild of John Whitelaw Lewis, a former laborer turned bank president who saw an opening as Jim Crow practices barred African Americans from White hotels; he wanted to give African Americans the same amenities found downtown. It had 25 apartments and 22 rooms, along with a ballroom for events.

But this came about in a tumultuous time for Black people in D.C. The hotel opened the same year that President Woodrow Wilson began his second term. In his first term, he had introduced segregation to the federal government and limited the hiring of African Americans, removing a pathway to the middle class.

In the summer of 1919, White mobs, including soldiers returning from World War I, led assaults on African Americans. These attacks across the country became known as the Red Summer.

Despite the obstacles and violence, emerging African Americans made the area surrounding U Street a destination for musicians and luminaries. Many of these performers, including Ellington, Fitzgerald and Cab Calloway, would flock to the Whitelaw.

While other historic hotels serving Black people, such as the Dunbar on 15th Street NW, would be demolished after desegregation, the Whitelaw remains firmly standing in a community that has changed around it.

803 Gibbon St.

Alexandria, Va.

In addition to hotels, the Green Book included “touring homes” - private residences where travelers could find lodging.

The home at 803 Gibbon St. was a boardinghouse for Black travelers in Alexandria, Va. (Michael A. McCoy/For The Washington Post)

Today, the 800 block of Gibbon Street in Alexandria is a quiet stretch of Old Town where many townhouses are noticeably more recent additions to the neighborhood. The largest home on the block, at the corner of Gibbon and South Columbus streets, has a much longer history.

In 1940, 803 Gibbon St. was listed in the Green Book for the third time. To gain a better understanding of this home, I turned to the 1940 Census.

James, the head of household, is listed as a 75-year-old bricklayer. His age means that he was either born during the last days of the Civil War or just after the Union victory.

There is no mention of income derived from operating a “touring home,” although a boarder is listed in the home along with his wife, their daughter, son-in-law and an aunt. The aunt, Susan Wilson, was 77 and born in Virginia, which means that she was possibly born in 1863, the same year the Emancipation Proclamation freed enslaved Black people in Confederate territories.

Reading these census records, I began to imagine travelers disgusted with the realities of segregation, and even further offended by the Confederate statue only recently removed a few blocks from their Gibbon Street lodgings, working through this mix of emotions with people born in the 1860s.

Visiting the Green Book sites in 2022, I was transported to a time when monumental change was on the horizon. My simple goal was to use addresses to see how many buildings were still standing and under what conditions. Yet, embarking on this journey, I witnessed drastic shifts in D.C. since 1940 and contemplated the ways African Americans moved around the reach of Jim Crow to community havens. Even with places I’d passed many times before, now with the Green Book in hand and with a completely different outlook, I was transformed.

When I posted a picture of my Green Book and the former University Garage on Twitter, people responded with stories of their grandparents’ interstate travels and their own desires to see what sites might be in their hometowns. This showed me that this entire exercise was deeper than my own hobby. The outpouring of support is part of a need to honor the past, not only through commemoration, but also in practice - in this case, by retracing the routes charted generations back to survive segregation, reflecting along the way.