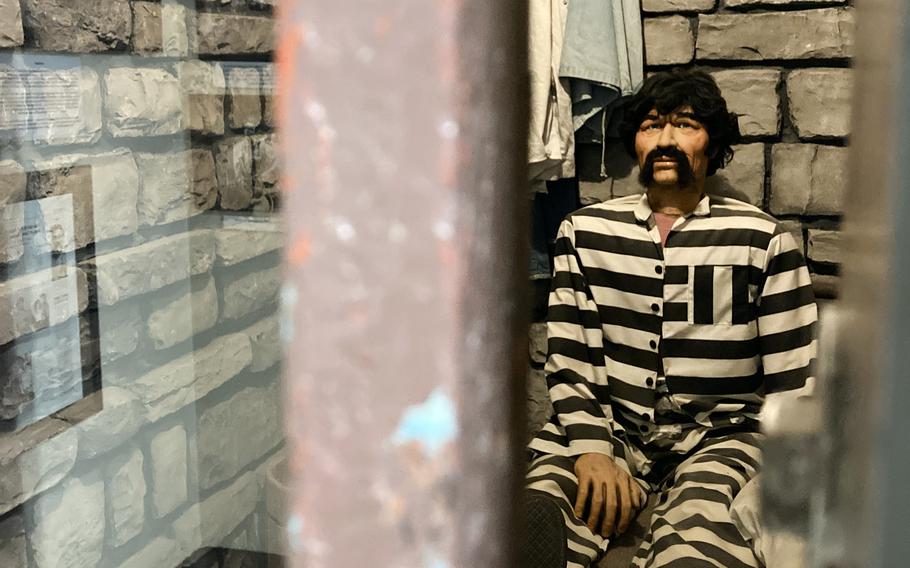

Sam the Perpetual Prisoner is an animatronic designed to resemble actor Charles Bronson. (Erika Mailman/For The Washington Post)

When visitors embark for Alcatraz, the island site of an infamous prison in San Francisco Bay, their moods are generally high. They're tourists, after all - they get a boat ride and a museum visit, and they may be fresh from the carnival atmosphere of Fisherman's Wharf, from which the ferry sets off. But on the return trip, they're often somber and sunk in moody contemplation.

Of course, a former prison is not exactly a feel-good destination. Nonetheless, touring one can provide insight into the changing - and sometimes unchanging - nature of incarceration in America. Historical attitudes toward crime and punishment can be a window into a bygone age as well as our own.

What follows is a thumbnail survey of prison museums throughout the United States, selected for their geographic spread; some are widely known, while others are small gems that deserve a closer look.

Alcatraz Island, San Francisco

Originally the site of a lighthouse and military fortification, Alcatraz in its early years imprisoned American soldiers convicted of crimes, treasonous citizens, Confederate prisoners of war and Native Americans who refused to send their children to assimilationist government schools. But with its designation as a federal penitentiary in 1934, Alcatraz became the place to send prisoners who had been causing trouble at other federal sites, such as Leavenworth in Kansas. The island prison hosted notorious criminals such as Al Capone (also held at Eastern State), George "Machine Gun" Kelly and Robert Stroud, the "Birdman of Alcatraz" who was memorialized in a movie of the same name.

Untenable operating expenses closed the prison in 1963 - for example, the approximately 1 million gallons of fresh water that had to be delivered by boat each week. In 1969, the island was occupied by Native American protesters; although they were forcibly removed 19 months later, the event is considered a turning point for Native American activism. Many ideas were floated about what to do with the site in the ensuing years, including installing a West Coast version of the Statue of Liberty on it. Today, the site is a National Historic Landmark and part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, run by the National Park Service, and it hosted more than 1 million visitors a year before the pandemic. The island, now a bird sanctuary that offers spectacular views of the city, belies its grim past.

Julianna Arias, a third-grade teacher in Gilroy, Calif., visited the island with her husband and family in December. Her 10- and 12-year-old children asked what prisoners had done to be sent there. "You don't want to really go into detail of some of the things they did," she says. "The Park Service did keep it G-rated."

National Big House Prison Museum, Represa, Calif.

Besides interpreting the history of the prison made famous by Johnny Cash's 1968 performance at Folsom State Prison, exhibits at this museum also feature prisoner artwork, including a eight-foot Ferris wheel constructed solely of toothpicks and glue. The museum sits on the grounds of the still-operational Folsom State Prison. (It's nerve-racking to drive in past the warden's sign warning visitors not to stop or turn around.) Completed in 1880, the structure once housed Charles Manson and has the distinction of being the first U.S. prison to have electricity.

In a cell reconstruction, a mannequin dubbed Sam the Perpetual Prisoner narrates the prison's early history. Sam, donated by Disney, was designed to resemble actor Charles Bronson. "A few years back, he quit working," says Jim Brown, the museum's operations manager. Apparently visitors were using him as a wishing well. "A guy came out and said: 'You know what the problem is? Well, his mouth is full of money. I pulled out $1.87 in change.' "

The museum recently reopened after its March 2020 pandemic-induced shutdown; Brown used the closure to do some retrofitting. For starters, he replaced its circa-1974 burnt-orange carpeting. Volunteers labeled a display of contraband shivs to identify which everyday objects had been transformed into knives: lemonade cans, lotion containers, toothbrushes.

According to museum volunteer Anthony Osuna, concrete surfaces are ideal for sharpening objects. "It's a sandpaper tool," he said. And guess what the cell floors are made of?

Texas Prison Museum, Huntsville, Texas

The highlight of this museum is its Bonnie and Clyde collection. Despite the fact that the duo's infamous rampage dates from the early 20th century, David Stacks, the museum's director, says even young visitors know who Bonnie and Clyde are. "Some movie depictions make them sound like a pair of folk heroes rather than the thugs they are," he said. "The fact is, they killed a lot of people, including law enforcement. [Our exhibit] gives a more historical portrayal."

Stacks says the public is drawn to the gritty nature of lawlessness. "How many shows do you see that have to do with CSI [crime scene investigators], police and emergency-type operations," he said. "People are enthused about the criminal elements."

Some of the artifacts at the museum may take the edge off that enthusiasm. Along with displays of the ball and chain that is incorporated into the museum's logo, a controversial artifact is "Old Sparky," the decommissioned electric chair that was in operation between 1924 and 1964. Manufactured by prisoners, it subsequently executed 361 of their peers.

"We see people changing history to make it softer, but that's not the way it should be," Stacks said.

Wiscasset Old Jail, Wiscasset, Maine

At the Old Jail, grooves in the wood floor bear witness to the shackled feet of sailors and debtors, and 100-year-old graffiti is visible on cell walls. Longtime tour guide and Lincoln County Historical Association board secretary Christine Hopf-Lovette said that although there is no anecdotal evidence of mistreatment in the jail, "it was definitely not a pleasant place to be."

When the jail opened in 1811, there were bars on the windows but no glass, and the only heat came from a coal-fired furnace in the hallway. Wiscasset was once a very busy port. "Sailors would be at sea for months at a time. They'd come into town and have a little too much fun," she said, and they would be thrown in jail for inebriation. "Everyone is so curious about what cells are like, and they realize it is just very, very grim." She said children as young as 9 were held here for weeks at a time for minor offenses such as stealing apples or sheep.

In the attached Jailer's House, built in 1839, the jailer's wife was on the hook for cooking meals for up to 50 inmates as well as her family. "In the 1800s, a law was passed that inmates were not to be fed lobsters, because they used them here for fertilizer. They thought it was inhumane," Hopf-Lovette said.

Fauquier History Museum at the Old Jail, Warrenton, Va.

A new exhibit at this circa-1808 jail focuses on runaway enslaved people. Executive Director Sean Redmiles got the idea for it after he found a box in storage containing jail records that included multiple references to runaways. "I was curious to learn the role the jail played in preventing freedom seekers from achieving their goal," he said. "It's a sad story for the jail, but an important one."

Redmiles and an intern searched online newspapers to find 90 instances of runaway enslaved people connected to Fauquier. The museum now displays an 1854 advertisement for a man named Ludwell, offering a $200 reward - which Redmiles says translates to several thousand dollars in today's money. "There was incredible value put into the body of an enslaved person," he said, "and the jail provided the means for slave catchers to get their money."

Besides this exhibit, a re-created 1820s jail cell and a maximum-security cell from 1909 provide visitors a dispiriting perspective. "Being physically in the space and reading about the conditions, people are more sober than when they first come into the room," Redmiles said. "I want to eliminate some romanticism about old jails and prisons."

Eastern State Penitentiary, Philadelphia

"The Big Graph" installation at Eastern State Penitentiary aims to open visitors' eyes. It's a 16-foot, three-dimensional bar graph. Sean Kelley, senior vice president and director of interpretation, said "it illustrates what this country's done in the last generation in terms of mass incarceration," including the jump forward in incarceration rates, racial disparity and comparison to other nations. "The U.S. is the top of the chart in the world," he said. Kelley designed the graph, inspired by a tabletop display at Ellis Island in New York.

Inside the penitentiary, visitors peer at Capone's cell, recently reinterpreted. "We discovered that the luxury treatment [believed to have been afforded him] may be a myth," Kelley said. Learning that Capone had a cellmate makes it unlikely that sumptuous furnishings adorned the space. Along with a synagogue that Kelley believes to be the first in American prisons, he touts the structure's architectural beauty.

"It's like a castle with all that drama, battlements, towers, arrow-slit windows, and you go inside and it looks like a church." Sunlight pours in from more than 1,000 skylights in the 30-foot barrel-vaulted ceiling, to encourage rehabilitation, remorse and penance, while the outside's intimidating bulk is meant to deter crime.

IF YOU GO

Alcatraz Island

Golden Gate National Recreation Area, San Francisco

415-561-4900

nps.gov/alca/planyourvisit/index.htm

This island's prison was made famous by many movies about its notorious inmates, including the classic "Birdman of Alcatraz" starring Academy Award-winner Burt Lancaster. Open daily 10 a.m. to 9 p.m.; hours vary by season. Stay as long as you want up to the last ferry of the day. No food for sale and limited restrooms. Inclusive ticket through official concessionaire Alcatraz CityCruises includes entry and ferry fare. Prices vary by type of tour: adults, $41-94.40; seniors, $38.65-87; children, $25-28.60; age 4 and under, free.

Eastern State Penitentiary

2027 Fairmount Ave., Philadelphia

215-236-3300

Described as "America's most historic prison," this penitentiary has a long and storied history. Open Wednesday through Sunday for daytime tours 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Adults, $17; seniors, $15; students with ID and those ages 7 to 12, $13; age 6 and under, free.

Fauquier History Museum at the Old Jail

10 Ashby St., Warrenton, Va.

540-347-5525

This small museum housed in an old brick jail is now focusing on the history of enslaved people who were jailed as runaways. Open Wednesday through Monday, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m.; closed Tuesday. Adults, $5; seniors 65 and over and military, $3.50; students with ID and those ages 6-17, $2; age 5 and under, free.

National Big House Prison Museum

312 Third St., Represa, Calif.

916-985-2561, ext. 4589

Housed on the campus of the Folsom State Prison, this museum contains a small but interesting collection. Open daily, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. General admission, $2; under 12, free.

Wiscasset Old Jail

133 Federal St., Wiscasset, Maine

207-882-6817

Dating to the 1800s, this jail housed debtors and inebriated sailors, among others. Open Saturday and Sunday, noon to 4 p.m. Adults, $10; ages 16 and under, free.

PLEASE NOTE

Potential travelers should take local and national public health directives regarding the pandemic into consideration before planning any trips. Travel health notice information can be found on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's interactive map showing travel recommendations by destination and the CDC's travel health notice webpage.