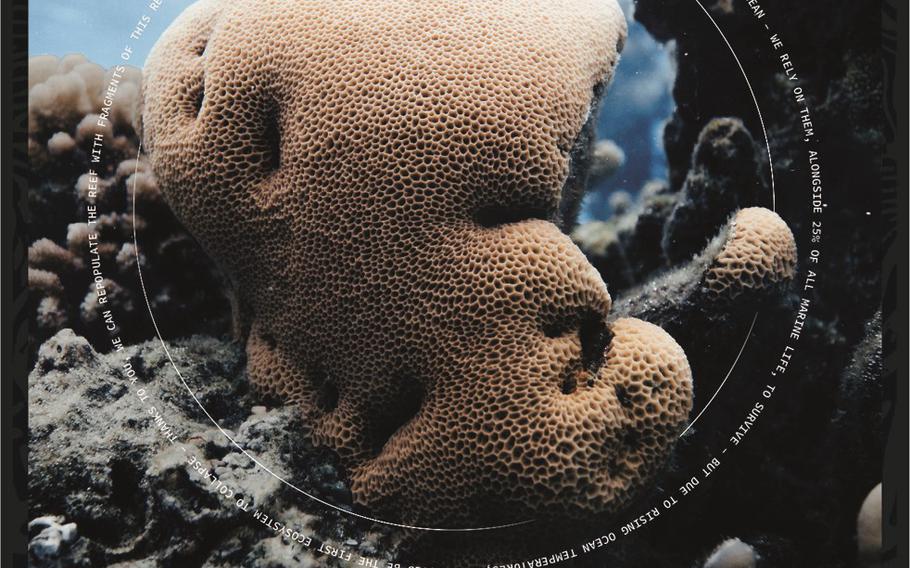

he Coral Gardeners team in Moorea, French Polynesia, identifies resistant species of coral and collects fragments. Those are attached to ropes in a nursery to grow so they can be replanted. (Ryan Borne/Coral Gardeners)

Healthy marine ecosystems are essential for human well-being, and millions of people around the world rely on coral reefs for food, protection, recreation, medicine, cultural connection and economic opportunities. So, the decline of coral reefs is not just an ocean-lover's issue; it's also a global problem that requires collaborative action.

"The situation with coral reefs is quite alarming," said Titouan Bernicot, founder of Coral Gardeners, a coral restoration collective in Moorea, French Polynesia. Studies have found that live global coral coverage has declined by 50 percent since the 1950s and is expected to decline by about 70 to 90 percent in the next 20 years.

Danny DeMartini, chief scientific officer and co-founder of Kuleana Coral Restoration, a nonprofit organization in Hawaii, said multiple stressors are overburdening corals. "There's an ecological equilibrium where coral growth rates can withstand some amount of natural pressure from waves, storms, some runoff," he said. But, he added, the accumulation of human-generated environmental stressors - including pollution, changes in sedimentation from development, increasing ocean temperatures due to global warming, and destruction caused by trampling and anchoring on the reef - has disrupted the balance. "It's becoming harder for coral growth to keep up."

Kuleana Coral Restoration’s Danny DeMartini, left, and Kaitlyn Loucks bring corals up from the sea table for replanting at restoration sites. (Blake Thompson/Kuleana Coral Restoration)

As the ocean continues to absorb carbon dioxide from emissions caused by human activities, "CO2 is binding with carbonate ions, making them unavailable for corals to build their skeleton," said Evelyne Chavent, a marine biologist and head of reef restoration at Coral Gardeners. "The corals become more fragile, prone to disease and unable to endure warming, cyclones or other disturbances. That's why we need to reduce our carbon footprint and help stabilize and restore the reef before it's too late."

Coral Gardeners grows resilient "super" corals in its underwater nurseries, then outplants and monitors them to help restore declining reefs in French Polynesia and contribute to global education and research.

Supporters can adopt a “super” coral on the Coral Gardeners website. ( Ryan Borne/Coral Gardeners)

Projects in other tropical destinations also aim to protect, monitor and restore reefs while inspiring stewardship. And some are getting visitors involved. Travelers to Bermuda, for example, can work with Living Reefs Foundation to plant or clean the corals in its underwater "garden," while divers traveling to Koh Tao, Thailand, can participate in hands-on marine conservation courses with the New Heaven Reef Conservation Program. In Australia's Tropical North Queensland, tourists can help with research and monitoring of the Great Barrier Reef through the Eye on the Reef program.

Although the coronavirus pandemic forced many industries to press pause, it had the opposite effect on some coral restoration efforts. "It gave us an opportunity," DeMartini said. He and the team went to work in the water, collecting coral colonies that have broken off and, after doing a health assessment, reattaching them to the reef. They've replanted 200 colonies with diameters of one to two feet, and they plan to reattach 1,000 to 2,000 more in the coming year. In Hawaii, where corals grow at a slower pace, DeMartini said it would take 30 to 50 years to grow a coral colony of the same size; direct restoration has an immediate effect.

The reef at popular Hanauma Bay on Oahu also benefited from the pandemic pause when Hawaii closed the nature preserve for eight months. Friends of Hanauma Bay President Lisa Bishop said that, in just a couple of months, it showed signs of regeneration. With no snorkelers kicking up sand or leaching sunscreen into the water, clarity improved by 56 percent, and, Bishop said, they started seeing coral recruitment (the process of coral larvae settlement, crucial for growth and recovery) on the inner reef.

Seizing the moment in this rare tourism intermission, Friends of Hanauma Bay proposed a coral restoration pilot project in July 2020. The Board of Land and Natural Resources approved it in September, and in October, corals - grown at the Hawaii Coral Restoration Nursery - were outplanted in Hanauma Bay, inspiring a private foundation to provide funding for endemic corals to be outplanted in the bay to restore corals destroyed by marine debris. "Collaboration is the gateway to achievement," Bishop said.

Hanauma Bay reopened in December with coronavirus-related restrictions: reduced hours of operation, reduced capacity (720 visitors per day compared with 3,000 to 6,000 per day pre-pandemic), an increased entrance fee for nonresidents and a reservations system. Although the state made these changes to protect human health, Bishop said continuing them beyond the pandemic would help protect the reef and improve the visitor experience, too.

In the Maldives, Reefscapers, a team of consultants and marine biologists that partners with hotels on reef restoration projects, was able to salvage 5,000 branching colonies and 2,500 massive colonies from Gulhi Falhu in the South Malé Atoll that would have otherwise been destroyed by development. During the summer of 2020, Reefscapers relocated the colonies to the lagoon and dive-center area near the Sheraton Maldives Full Moon Resort on Furanafushi Island. According to Thomas Le Berre, a coastal oceanographer and co-founder of Reefscapers, this was no small task at a time when the pandemic had sent many international biologists away and restrictions prevented the team from going ashore on Furanafushi Island. The replanted corals have already attracted marine life to the lagoon, and guests at the hotel can sign up for workshops and snorkeling tours led by a Reefscapers marine biologist.

Since the start of the pandemic in French Polynesia, Coral Gardeners placed more than 5,000 super coral fragments in its nurseries and transplanted 755 super corals onto the reef, grew its team and partnered with Silicon Valley engineer Drew Gray to develop the first ReefOS.

One of the challenges of reef restoration projects scattered around the world is a lack of cohesiveness. ReefOS, if scaled globally, has the potential to change that. According to Gray, this technology uses an artificial intelligence computer vision model and in-situ physical and chemical sensing - underwater cameras and sensors monitored by the team. "Our technology is providing an in-depth look at the biodiversity of the reef ecosystem at a level of detail that's impossible for a human to accomplish. It's like having a marine scientist watching the reef at every second of the day."

And ReefOS will help Coral Gardeners achieve another goal: "We exist to revolutionize ocean conservation and generate collaborative action worldwide to save the reef," founder Bernicot said. Coral Gardeners will collect data to share with the larger conservation community, and "with the live stream launching in October, we'll essentially be able to connect the world to the corals growing in front of my house, and create immersive experiences for our (global) community."

One way to help protect coral reefs is to choose sunscreen products without oxybenzone, such as Raw Elements, which is available in dispensers at Kahaluu Beach Park in Hawaii. (Cindi Punihaole/Kahaluʻu Bay Education Center)

How You Can Help

There are plenty of ways travelers can do their part - from the couch now, and in future travels.

Donate. Although travel is discouraged because of coronavirus surges, you can support coral conservation from home. Donate to restoration projects, offer your skills virtually or adopt a coral. Funding generated by adoptions helps organizations such as Coral Gardeners continue their restoration and research. "People feel connected to their coral, they learn about reef restoration and become part of our community," Bernicot said. "That's how we raise awareness. And that's how we're building the reef of tomorrow together."

Prepare. When you do plan a trip, book accommodations that support conservation, and look for eco-friendly, expert-led activities, such as the Coral Nurture Program in Australia, coral restoration at Coco Palm Dhuni Kolhu in the Maldives, and Malama Hawaii experiences. Marine biologist Gareth Phillips, director of Reef Teach in Cairns, Australia, suggested checking for global and local certifications, such as EarthCheck and Ecotourism Australia.

Pack smart. Skip sunscreens and toiletries that contain oxybenzone and other chemicals; opt for mineral-based instead. Kapono Kaluhiokalani, the director of outreach at Kuleana Coral Restoration, recommended packing clothing, such as hats and long-sleeve rash guards, that cover more skin, so you can reduce sunscreen use overall. And remember to pack a reusable water bottle, utensils and bag, so you can avoid single-use plastic.

Show consideration. For coral conservation and your safety, "respect the ocean. Look but don't touch or step on corals or marine life. Observe signs and directions from lifeguards," Kaluhiokalani said. And be open to learning from locals, such as theKahaluu Bay ReefTeach volunteers in Hawaii.

Reduce your carbon footprint. "The corals dying in front of my house, it's not just because of fishermen or the impact of chemicals, et cetera. It's global warming," Bernicot said. "The most important thing is to see what you can do on a daily basis to reduce your carbon footprint." Consider choosing human-powered transportation (such as bicycles), reducing resource consumption and offsetting carbon, especially when you travel.

The vast decline of coral reefs globally can feel like an overwhelming problem beyond your influence. Phillips advises taking small steps by focusing on the daily habits you can change now. If everyone does so, he wrote, "it will add up to billions of people making a world of difference."