A painting of Mt. Fuji at the Daini Kotobuki-yu sento in Edogawa Ward, Tokyo. (The Yomiuri Shimbun/The Japan News-Yomiuri)

From the stately changing room of a nearly 60-year-old sento public bath in a residential area of Edogawa Ward, Tokyo, you can enjoy a majestic view of Mt. Fuji. But only through a painting. With white clouds floating in a blue sky, the mural connects the men’s and women’s baths at the Daini Kotobuki-yu sento.

It was created by 38-year-old artist Mizuki Tanaka, said to be one of only three artists who paint public bathhouses in Japan. Tanaka paints 20 to 30 public bathhouses a year, on walls that are usually 10 meters wide.

“I start in the morning and paint all day when the bathhouse is closed,” she said.

Tanaka painted the mural at Daini Kotobuki-yu in November. She usually consults with the client before deciding what to paint, but Daini Kotobuki-yu let her have free rein over the design.

“For the first time in a while, I decided on a standard public bath painting,” she said. “As soon as you walk in, you see Mt. Fuji against a clear blue sky, even when it’s dark outside. I hope the painting will brighten someone’s day or help them relax.”

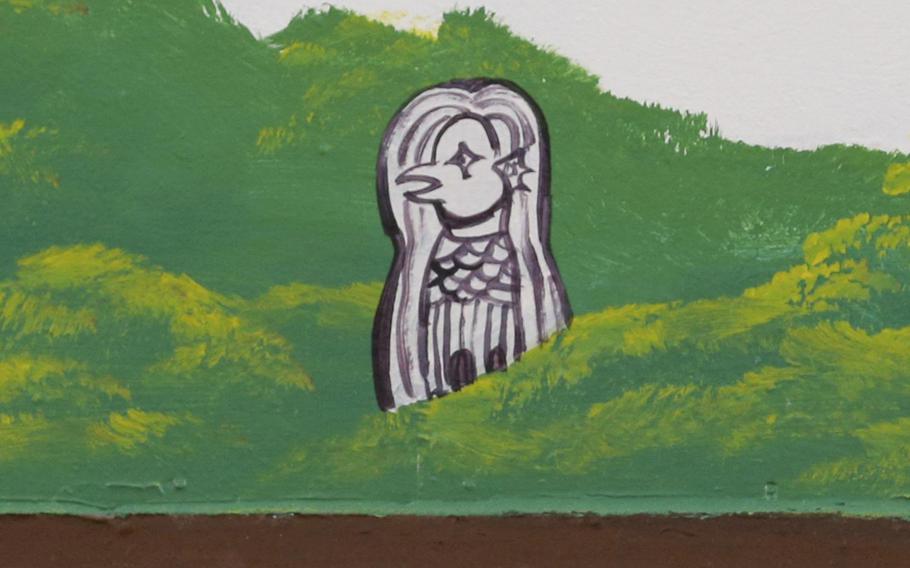

She also included an amabie, a yokai supernatural being that protects against diseases.

Amabie, a yokai supernatural being that protects against diseases, is included in the mural at the Daini Kotobuki-yu sento. (The Yomiuri Shimbun/The Japan News-Yomiuri)

Owner Kazuyuki Shigihara, 64, started his career as a boiler stoker at a public bath run by his wife’s parents after quitting his job. Shigihara asked Tanaka to paint the mural nearly 10 years ago to “breathe new life” into his sento.

However, fewer people use public bathhouses these days. Shigihara has been employing various methods to attract new customers, including creating “Oyu no Fuji,” a mascot for the local branch of the public bath association.

Regular visitors to the sento include people who live alone and working couples. Even though they have a bath at home, they tend to find it easier to come to the public facility.

The number of families who came to the sento fell sharply during the pandemic. But to Shigihara’s surprise, young customers increased, possibly because they needed a change of scenery after working from home all day.

Shigihara repeatedly sanitizes the sento and has put a sign in the changing rooms that reads “mokuyoku,” meaning bathe in silence.

Having murals in public baths is said to have originated in the early Taisho era (1912-1926). They are called “background paintings,” and are mainly found in public baths in Tokyo. In rural areas, the walls of bathhouses are either left blank or have tile art.

Tanaka majored in art history at Meiji Gakuin University. For her thesis, she studied how Mt. Fuji was depicted in modern times through art at public baths.

She was apprenticed to the painter Morio Nakajima, who was designated as a contemporary master craftsman, after watching him paint a mural at a public bath. Now an independent artist, she works with exhibitions and collaborates with companies at advertising events.

More and more public bathhouses are closing because the owners are getting older and there are fewer customers. There are also concerns about the future of sento paintings, but Tanaka uses her art history background to think of ways to keep the art form alive. One method she devised is to form a group of artists and work together to create a mural.

“If a lot of people work together on a single piece, they can stably continue the work and also pass on the techniques,” she said.

This method was also used by Rembrandt and the Kano School, among others.

“Osamu Dazai made fun of scenery including Mt. Fuji in his novel ‘Fugaku Hyakkei’ (One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji), saying it was like a painting in a bathhouse,” Tanaka said. “Sento art may not be considered high-end, but what fascinates me is that bathhouses in a small corner of the city have been painted this way for a long time.”

Sento murals also raise the question, what is art?

The Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum in Koganei, Tokyo, has been holding the special exhibition “The Sento: The history and the culture of the bathhouses in Tokyo” since last year. Some of the pieces have been changed to introduce the culture of public baths to domestic residents as well as to foreigners visiting the country.

The exhibition traces the history of public bathhouses in Tokyo from the Edo period (1603-1867). The descriptions of the bathhouses’ architecture are particularly thorough and describe “Tokyo-style Sento,” which feature large roofs and coffered ceilings similar to shrines and temples.

Curator Manae Kobayashi said that particular style was popular when public baths were being rebuilt after the Great Kanto Earthquake.

The impressive buildings were a sign of the times, when public bathhouses were thriving as reconstruction took place nationwide. When building the Kodakara-yu sento in Tokyo in 1929, the owner is said to have brought in carpenters from his hometown in Ishikawa Prefecture and paid more than double the average rate.

The sento was built in the Irimoya-zukuri architectural style, which has karahafu gables. The carvings on the underside of the roof, such as gegyo and unokedoshi decorative wooden boards, were made by skilled craftsmen. Kodakara-yu was later rebuilt at the museum to preserve the historical building.

Outside of Tokyo, sento designs were deeply influenced by local culture. In Kyoto, Western-style architecture was required for sento to differentiate them from the traditional machiya-style buildings. Unlike Tokyo, the interiors were decorated using tile art as opposed to paintings.

“Kyoto’s public baths have a unique culture of decorating their sento with tiles,” Kobayashi said.

Reverse glass paintings of the couples Oishi Kuranosuke and Okaru, and Yamauchi Kazutoyo and his wife, used to adorn the walls of sento Ine-yu, located near Fushimi Inari Taisha shrine in Kyoto, but can now be seen at the exhibition. The pieces are said to have been made by a movie billboard painter around the beginning of the Showa period (1926-1989). This shows the vitality of the time, when film studios were being built one after another.

The fourth part of the museum’s sento exhibition will run through Sept. 12. Online reservations are required.