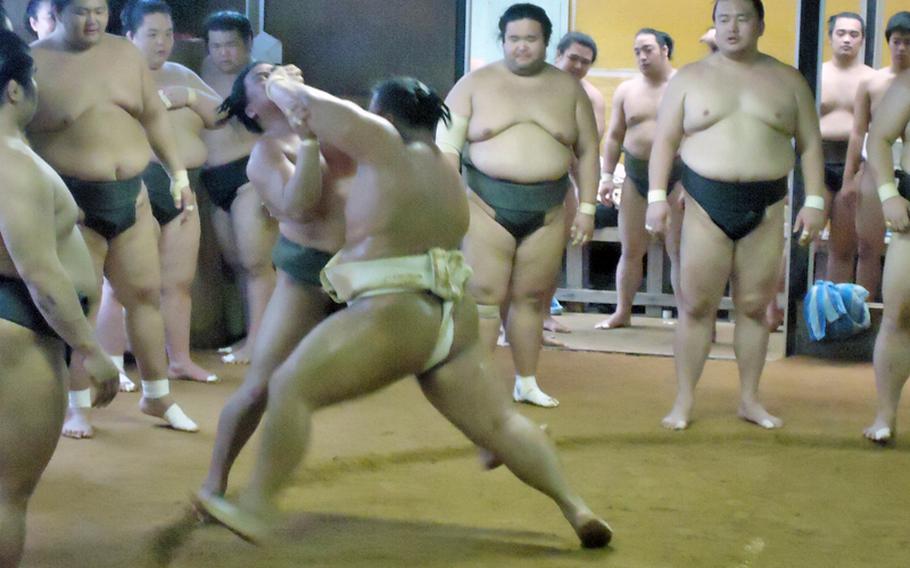

The art of sumo wrestling is part tradition and part brute force. Here, one sumo wrestler from the Sadogatake sumo stable in Fukuoka uses a shot to the face of another to get him out of the ring. (Matthew M. Burke/Stars and Stripes)

As 383-pound sumo wrestler Kotoshogiku walked past me, the wooden floor shook. It was as if a mini earthquake had struck and sent vibrations up my spine.

I probably shouldn’t have been stunned after taking just one look at the redwood trunk-sized colossus, but I was.

“He is a big boy,” is all I could manage to utter as he walked around the room after a workout and shower in boxer shorts that probably could have served as bed sheets for most.

Kotoshogiku, a baby-faced ozeki, which means champion — the second-highest sumo rank under yokozuna — was affable and kind. He walked with a swagger on par with that of a Kobe Bryant or Alex Rodriguez, yet he seemed to take pleasure in connecting with his fans. He posed for pictures with everyone in my group who wanted one, and he signed countless autographs. Young Japanese kids approached him meekly, as if afraid to speak to the sumo superstar. They gave him a long bow to show their great measure of respect as they shook hands, their parents smiling widely as they snapped photographs.

When it was my turn, I got close to him and held out my hand to shake. He grabbed it and held it up, smiling at the camera as if we were long-lost friends. It was a very kind gesture.

To be perfectly honest, I got my picture taken with him because he is a famous sumo wrestler and I am an American who hadn’t the slightest clue about the sport. He could have been any behemoth in a loincloth for all I knew. I really had no idea who he was or what sumo was all about until I spent a Saturday at the Sadogatake sumo wrestler stable in Fukuoka, about two hours by bus from Japan’s Sasebo Naval Base. My level of interest in the sport, as well as my thoughts on the athletes who participate, was all about to change drastically.

The journey to the famed stable began as I arrived at Nimitz Park in Sasebo before daybreak and boarded a Morale, Welfare and Recreation bus to the stable, which features two current ozeki wrestlers, a rare feat I had read beforehand.

The building outside was unassuming and looked like a shipping warehouse. We were ushered inside by staff and took off our shoes. I felt like I was going to watch a cockfight as the building was dimly lit and its central room was not visible from the open door or even the foyer area.

As we walked around a corner, we saw nearly two dozen men, adolescents and small children working out under bright lights around a dirt sumo ring in belts that leave little to the imagination. A crowd stood in the shadows around them, watching silently.

Sumo wrestling started as a religious tradition and goes back to the time of Japan’s imperial court. The point is to grapple until one man is forced from the ring or a part of his body other than the soles of his bare feet touches the reddish-brown dirt inside. To American spectators, the training is often more interesting because the tournaments display as much ritual as fighting.

I watched as two rotund men squared off in the center ring. They knelt down into what looked like the stance of linemen in American football. Then there was a flash as they hurtled themselves toward one another without warning, like two trucks in a head-on collision. Then we heard the thunderous crack of muscle-covered blubber on muscle-covered blubber.

Smack.

I shuddered at the sickening sound.

The stable master — a former sumo wrestler himself — sat behind them in a huge track suit, critiquing the men. In my head, I could hear the judge from the original Mortal Combat video game say, “Excellent,” after each successful takedown.

I saw several of these large men pushed seemingly until the point of exhaustion. I was impressed by their stamina and strength despite their girth. It was highly physical, and many took blows to the face or were bloodied as they hit the dirt over and over again.

As soon as one man was clearly the victor, the rest of the sumo in attendance would rush him with their hands in the air, shouting. I thought this was to stop him from going after the felled opponent if emotions ran high. However, I was told they were begging to be picked to fight next.

Suddenly, a large Caucasian ozeki, standing just shy of 7 feet tall and weighing 340 pounds, entered the room wearing a white belt. The crowd buzzed and bulbs flashed. This was the towering Bulgarian sumo superstar Kotooshu, the first European to win an Emperor’s Cup.

Kotooshu stretched as the other wrestlers kept hitting one another. Then it was his turn. And the giant who had once been an Olympic wresting hopeful, but who tipped the scale out of contention, did not disappoint. He easily dispatched almost every fighter in the room without so much as breaking a sweat. He was unmovable, and his technique was very impressive as he pushed each man out of the ring with precision. Kotoshogiku entered the room in much the same fashion.

The Bulgarian stepped out as Fukuoka’s hometown hero began fighting each man. He too made quick work of the cast of doughy understudies, setting the stage for an epic training battle between the two ozeki. Kotooshu reached the rank of ozeki in 2006 and Kotoshogiku this month, so in a way, it was the old guard versus a new up-and-comer: King Kong versus Godzilla.

The Bulgarian is perhaps one of the best-known sumo wrestlers in Japan, appearing in television commercials and shows. One of my friends commented that he is like Michael Jordan in Japanese culture. I had seen him fight on television this past summer. Now he was right in front of me.

The titans squared off, and time after time they hit each other with ferocity. Kotooshu, who has been hampered with injuries throughout his career, appeared a step late and unable to get as low as his much shorter and explosive fellow ozeki. They pushed each other, grabbed each other’s belts and swung the other man around, and stretched each other to an upright position with a well-placed stiff arm under the other man’s chin.

And then it was over.

All of the fighters were covered in dirt, saturated in their own sweat. They glistened in the bright lights that hung over the ring; they were exhausted. A young boy blotted at Kotooshu’s backside and the long bloody gash he had received there.

We went outside for a break as the fighters prepared a post-training meal for us. A light rain fell. When we returned, the mammoths served us the food that makes them so big, Chanko-nabe, which is a soup with vegetables and meat. They had been cooking it in large pots all day. They also served us potato salad and corn, plates of fish, rice, and numerous bottles of beer.

We sat on the floor and ate with the sumo. The Chanko-nabe was delicious; however, it seemed too healthy to support the girth of the men before us. Fish, cabbage or lettuce, tofu and broth … I wondered out loud how they ate it and got so big. One of my bilingual Japanese friends asked one of the servers.

As it turns out, the sumo get up every morning at 4:30 a.m. They don’t eat breakfast, and they train hard until 12:30 p.m. Then they eat a large meal for lunch, which includes Chanko-nabe and other dishes such as noodles, and go to bed so that they cannot work off any of the food. They wake again for dinner, eat, and go back to bed, only to repeat the following day. This adds fat to their strong core of muscles that they develop through training, and doesn’t allow for any of it to be burned off.

After lunch, the ozeki emerged from the showers to get their hair done by stylists in a corner of the room. Kotoshogiku talked on his cell phone, looking like a total prima donna. Kotooshu just stared forward, now wearing warm-up pants, a stark contrast to the man thongs they wore earlier.

We mingled with the ozeki before we left. Kotooshu was gracious and posed for photos, but you could tell he didn’t want to. He seemed a bit annoyed. With a tournament in a few weeks, I could understand. We were a distraction. Kotoshogiku, on the other hand, was loving the newfound attention from his recent promotion to the elite, and he hammed it up as much as possible.

I went from thinking sumo wrestling was a bunch of fat guys tickling each other in a diaper, to being a fan who appreciated their work ethic, the sacrifice of their bodies and long hours of difficult training. The next tournament was scheduled a few weeks away in Fukuoka, and I planned on being there, cheering on the giants.