Courtroom 600 in the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, Germany, hosted the proceedings of the International Military Tribunal, which convened in November 1945 to try senior Nazi officials. (David Edwards/Stars and Stripes)

The phrase “trial of the century” has been used often enough for high-profile defendants.

But if any instance of criminal justice ever deserved that title, it took place in Nuremberg, Germany, between Nov. 20, 1945, and Oct. 1, 1946.

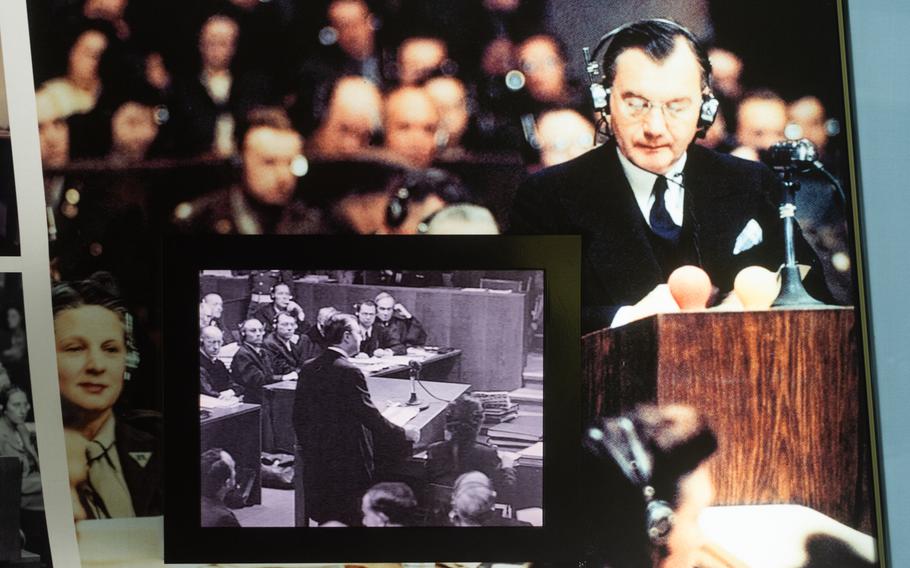

American prosecutor Robert Jackson was the leading light of the International Military Tribunal, the first of the landmark Nuremberg trials. He appears throughout the Memorium Nuremberg Trials exhibition in the east wing of the city's justice complex. (David Edwards/Stars and Stripes)

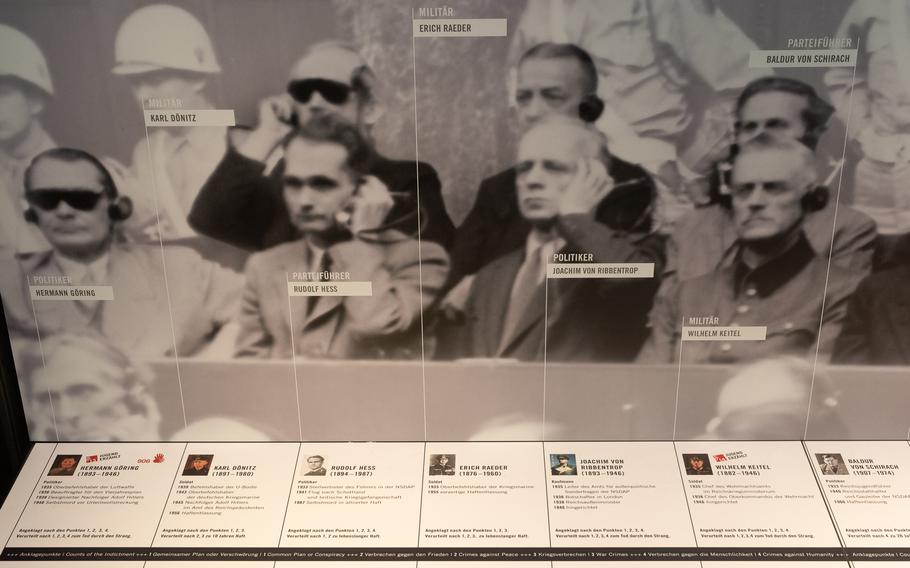

Officially called the International Military Tribunal, the first of the landmark Nuremberg trials made defendants of 21 leading Nazis, a veritable who’s who of incarnate evil that included Rudolf Hess, Hermann Goering and Joachim von Ribbentrop.

Proceedings were held in Courtroom 600 in the east wing of the Palace of Justice. For visitors in the present, the courtroom and the Memorium Nuremberg Trials exhibition in the same building yield a powerful and indelible experience.

Boston architect Dan Kiley oversaw an enlargement of Courtroom 600 in 1945 for the Nuremberg trials at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, Germany. The courtroom was later restored to its previous configuration. (National Archives)

In American prosecutor Robert Jackson’s opening statement, footage of which is shown in the exhibition, he intoned: “The wrongs which we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant and so devastating that civilization cannot tolerate their being ignored, because it cannot survive their being repeated.”

The 21 defendants in the first of the Nuremberg trials were among the foremost Nazi war criminals. They are portrayed on two information boards at the Memorium Nuremberg Trials exhibition in the German city. (David Edwards/Stars and Stripes)

Those wrongs were encapsulated in the groundbreaking counts of the indictment such as crimes against peace and crimes against humanity. The defendants were also charged with war crimes and conspiracy to wage aggressive war.

Nazi organizations including the Gestapo and the SS were named as conspirators along with individuals. Courtroom 600 thus became the cradle of accountability for atrocities the world over.

I felt reverence as I gazed around it from the gallery, taking particular note of the imposing bronze crucifix and the exquisite wooden wall panels and ceiling.

The magisterial scene is completed by a marble-encased door topped with a bronze cartouche and statues representing Roman and Germanic law. Light streaming in through the four windows cast a glow on the marble.

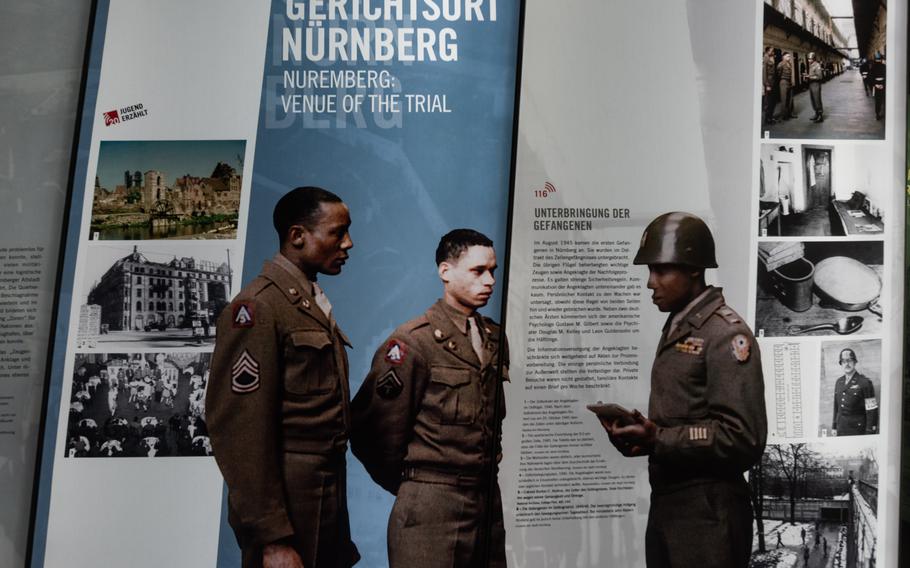

U.S. soldiers were key in most aspects of the first Nuremberg trial, from collecting evidence to guarding prisoners. The middle photo on the left shows the Grand Hotel, which the U.S. Army refurbished to accommodate International Military Tribunal personnel. (David Edwards/Stars and Stripes)

One floor up, the exhibition traces the development of war crimes jurisprudence from the Geneva Conventions to the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

Between those bookends is a collection of imagery and artifacts offering an immersion into the marquee event.

A world map with accompanying information cards at the Memorium Nuremberg Trials exhibition in Nuremberg, Germany, shows the extent of armed conflicts and war crimes between 1945 and 2000. (David Edwards/Stars and Stripes)

One noteworthy aspect of the exhibition for me was its portrayal of the U.S. Army’s indispensable role before, during and after the International Military Tribunal.

It “had stood in the forefront as far as the collecting of evidence was concerned and in addition, it had taken care of security and the whole logistics of the trial process,” according to a booklet sold on site.

Benches in the Memorium Nuremberg Trials exhibition in Nuremberg, Germany, represent the prisoners dock. Scenes of Nazi defendants in the first trial are projected on the wall behind the benches. (David Edwards/Stars and Stripes)

Two benches mimicking the prisoners dock are placed between panels depicting the defendants, while scenes from the trial are projected on the walls behind them. American soldiers stand guard as the accused follow the proceedings in front of them.

The U.S. Army also handled all the accommodations challenges, renovating the landmark Grand Hotel across from the central train station and putting up the press corps in Stein Castle.

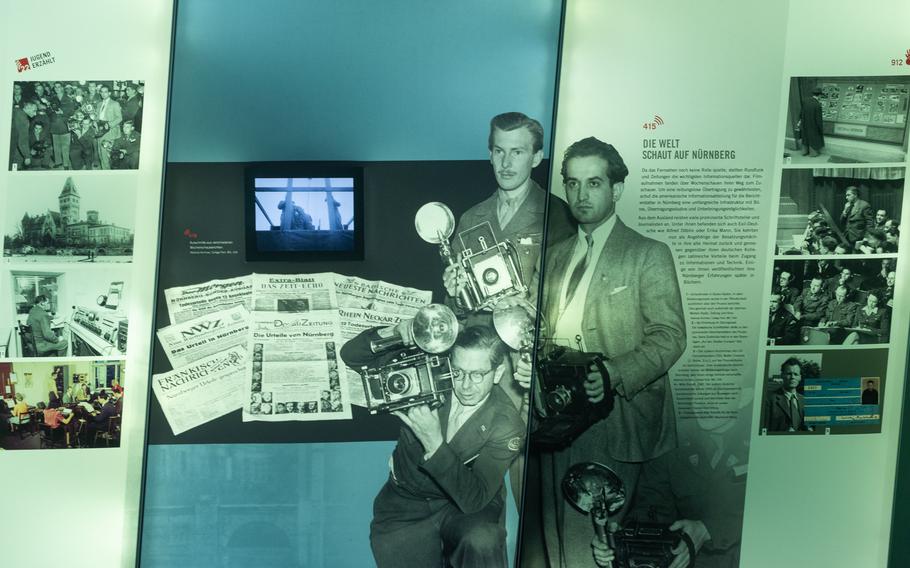

Luminaries who covered the International Military Tribunal in 1945-46 included Walter Cronkite, Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck. Media members were housed in Stein Castle, shown in the second picture from the top on the left side of this exhibit. (David Edwards/Stars and Stripes)

American GIs shuttled a young Walter Cronkite, author John Steinbeck and reporters from around the world between the courthouse and the castle, which is owned by the family that operates the adjacent Faber-Castell pencil manufacturing empire.

The International Military Tribunal press camp was at Stein Castle in suburban Nuremberg, Germany. The castle is the ancestral home of the Faber-Castell family, of pencil-making fame. (David Edwards/Stars and Stripes)

Some of the film footage entered into evidence before the tribunal is screened in the exhibition, which additionally weaves in bits of witness testimony and citations of the immense trove of incriminating documents that Army investigators scouring Europe had unearthed.

The record amassed by the International Military Tribunal and displayed in part in the Memorium offered irrefutable proof of the Holocaust and a litany of other crimes. It was and is an unvarnished look at the Hitler regime’s depraved indifference to human life.

As a result of the trial, Goering, Ribbentrop and 10 others went to the gallows. Hess and Albert Speer received prison sentences, while Hans Fritzsche, Hjalmar Schacht and Franz von Papen were acquitted.

Jackson and his colleagues paved the way for a permanent legacy, as demonstrated by the final portions of the exhibition, titled “Follow-up Trials” and “From Nuremberg to The Hague.”

The Grand Hotel in Nuremberg, Germany, provided exclusive lodging for Nazi Party rallies. The U.S. Army requisitioned and rebuilt it to accommodate the International Military Tribunal delegations. (David Edwards/Stars and Stripes)

A lineage of international justice, they touch on the 12 subsequent Nuremberg trials, the Tokyo Trial and assorted war crimes tribunals of recent decades.

In addition to engendering new legal forums and concepts such as the famous Nuremberg Principles, the tribunal served as the birthplace of simultaneous interpreting. The necessity of seamless, real-time communication in English, French, German and Russian spurred IBM to develop the system that now facilitates business at the United Nations.

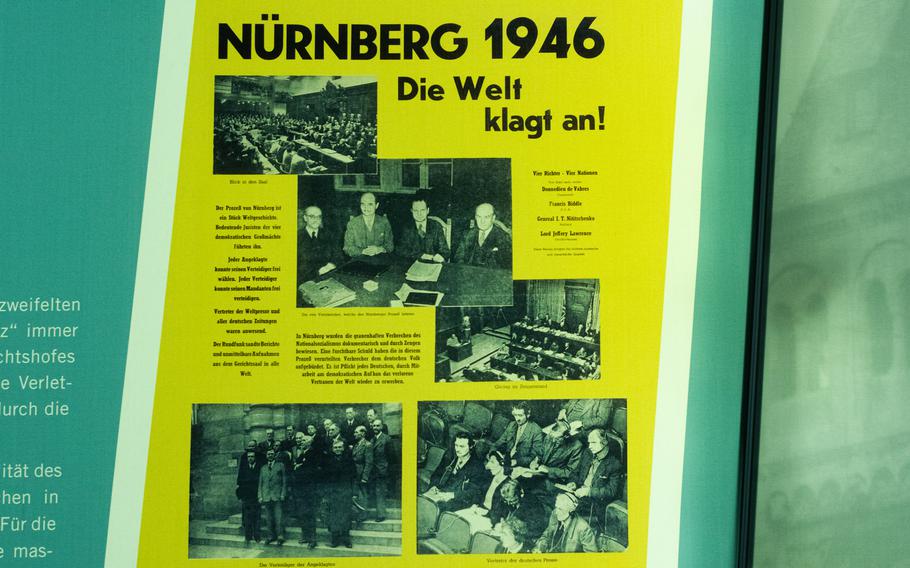

The Memorium Nuremberg Trials exhibition includes a 1946 poster that helped inform the German public about the rationale for bringing the Nazis to justice via the International Military Tribunal. The headline reads "The world accuses." (David Edwards/Stars and Stripes)

Speaking of translation, although the Memorium visuals are in German only for the most part, all their information is furnished in other languages via audio guides.

Handset codes at each exhibit allow visitors to choose between audio presentations geared toward adults or children.

The east wing of the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, Germany, houses Courtroom 600 and the Memorium Nuremberg Trials. The courtroom's four large windows are visible in this exterior shot. (David Edwards/Stars and Stripes)

I concluded my Palace of Justice stopover with a walk along the Pegnitz River, following Reutersbrunnenstrasse behind the justice complex past the prison. The cellblock where the original 21 Nazi defendants were detained no longer exists, however.

On the banks of the Pegnitz, I sat down for a snack and a bit of reflection on the poignant testimonial to what Jackson called “one of the most significant tributes that power has ever paid to reason.”

On the QT

Address: Baerenschanzstrasse 72, Nuremberg, Germany

Hours: Through March 31, Wednesday through Monday, 10 a.m.-6 p.m.; closed Tuesday

Cost: Admission is 7.50 euros for adults, 2.50 euros for students and children ages 4 and up. “The Nuremberg Trials: A Short Guide” costs 6.80 euros. A gift shop book about the exhibition is sold for 8 euros. Nearby street parking is paid on weekdays, free on weekends.

Info: https://museums.nuernberg.de/memorium-nuremberg-trials/