A child on a school trip looks over a diorama of historical Kaiserslautern at the Theodor Zink Museum. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)

A bygone era when U.S. troops and their families stationed in Kaiserslautern, Germany, lived in a community affectionately dubbed “Little America” is being brought to life at the city’s museum of local history.

An exhibition at Stadtmuseum Kaiserslautern that runs through Jan. 28 traces the lifespan of the American Fliegerstrasse housing complex, which occupied the north slopes of the city until its demolition in 2011.

The exhibition, “Fliegerstrasse, Blutacker und Amiwissje,” is in the Wadgasserhof, a building constructed by monks during the Middle Ages. It is across from the Theodor Zink Museum, where permanent displays focus on Kaiserslautern’s growth over the years.

A visit provides an interesting look into how Germans viewed relations with the Americans in the area prior to 9/11, when security tightened and fences went up between area residents and U.S. military personnel.

Kaiserslautern once had a neighborhood along Fliegerstrasse where American military officers and their families lived, as shown by this postcard from the 1950s. (Stadtmuseum Kaiserslautern)

In the 1950s, Americans began moving into a block of 10 large housing complexes on a hill on the north side of town. Postcards from the time show huge houses in rows, offset from the road by spacious lawns in the quintessential American suburban design.

German children would wander into the unfenced neighborhood to go sledding with their American pals.

A vivid theme of the exhibit is one common to stories of German and American relations in the area: the clash between the human desire to connect and the bureaucratic need to control access and maintain security.

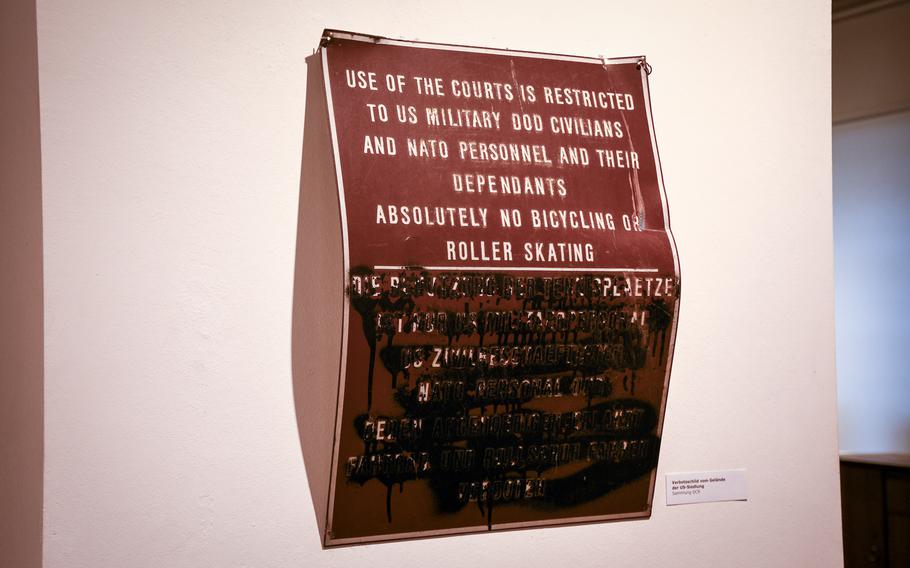

The depiction of a sign at the Fliegerstrasse basketball court at the museum illustrates this best. An English message in the top half says use of the court by anyone not affiliated with the U.S. military is forbidden. The bottom half, with the warning in German, is completely blacked out by defiant graffiti.

A sign for the basketball court at Fliegerstrasse forbids Germans from playing there, but many did anyway. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)

Despite warnings from military police, Germans and Americans kept meeting at the basketball court to play, according to emails showcased at the exhibition.

They were written by Ralf Vester, who grew up in Kaiserslautern and went to school next to the housing complex.

“They were something special, the Americans,” Vester wrote. “That was always a touch of the big, wide world for us children and young people.”

But after 9/11, security measures tightened at U.S. bases across Germany. In 2003, the Americans tried to fence off the housing area with roadblocks, even though it was in the middle of the city. After this failed, homes started to go vacant.

The American homes at Fliegerstrasse were demolished in 2011, as seen in this photo on display by Herbert Rohmer. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)

The area was handed over to the German government in 2009 and demolished in 2011. Today, apartment complexes stand where service members once lived.

I was struck by the durability of the impression the residents of Little America made on the people in the area.

And yet, for an exhibit that portrays relations between Germans and Americans, there is a distinct lack of text in the language of the latter. All but one of its captions are in German without English translation.

Much of what I learned came from Google Translate and speaking to staff at the museum, who acknowledged that there should have been more translations.

The Theodor Zink Museum has permanent exhibits that focus on Kaiserslautern’s growth over the years. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)

I also enjoyed the free permanent exhibits at the Theodor Zink Museum next door, especially the tabletop diorama of historical Kaiserslautern. The presentation on the impact of World War II on the region, which survived heavy bombing by U.S. and allied forces, was haunting. The permanent exhibits had binders with an English guide, which was helpful.

While the museum is small, it’s laid out well and worth an afternoon trip for those wanting to know more about how the region’s growth.

Stadtmuseum Kaiserslautern

Address: Steinstrasse 48, Kaiserslautern, Germany

Hours: 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Wednesday through Friday; 11 a.m.-6 p.m. Saturday and Sunday; closed Monday and Tuesdays

Cost: The permanent exhibition in the Theodor Zink Museum is free. The cost for the exhibit is 4 euros for adults and 2.50 euros for students with a student identification card.

Information: Phone: 0631 365-2327; online: tinyurl.com/4jztb364