The Caledonian MacBrayne ferry line operates routes to 54 ports and harbors on 35 islands and mainland cities across 200 miles of Scotland’s west coast. (Liza Weisstuch/For The Washington Post)

Colonsay is a roughly 10-by-2-mile island in Scotland's Inner Hebrides. It has a bookstore, two galleries, two distilleries making gin, a general store and the Colonsay House, a Georgian home owned by a lord. The year-round population is about 130. In the post office, a sheet of paper tacked to the wall notes the time of low tide at the Strand, the approximately mile-long beach between Colonsay and nearby Oronsay (population: six). Postal workers use it to time their daily runs to Oronsay and back. It's useful to tourists, too. During low tide, they can - and should - walk across to see the island's 14th-century monastery ruins and Celtic cross.

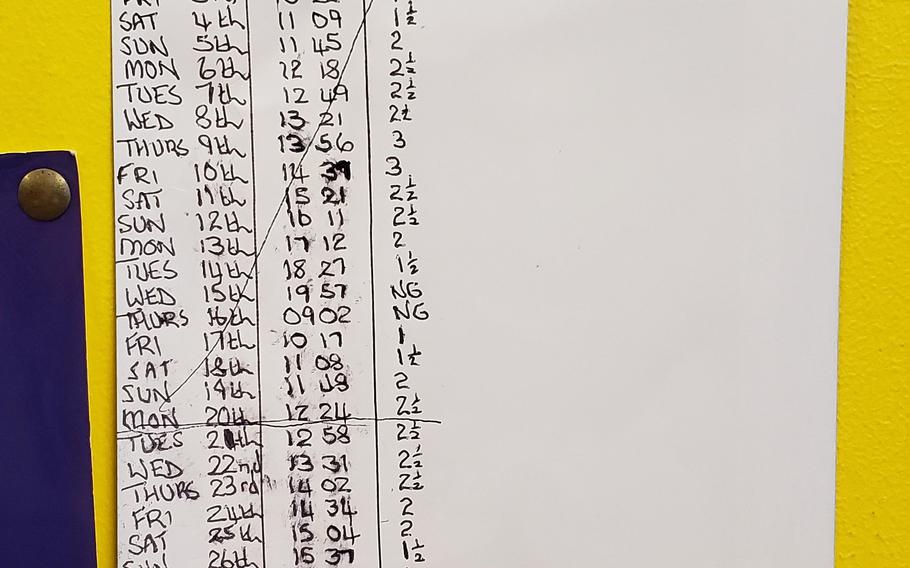

A list of daily low-tide times hangs in the post office in Colonsay. (Liza Weisstuch/For The Washington Post)

"People here are always talking about the tide. Even today, the ferry was affected - it docked at the pier an hour late," said Jane Rose, the postal clerk and an artist who makes playful assemblages with beach litter. When she's not on the job, you'll find Keith Rutherford, who became postmaster after logging 100,000 miles delivering mail on the island's 12 miles of road. If you want to buy books and the Colonsay Bookshop is closed, you ask Keith or Jane for the key.

"You let yourself in, put the lights on and have a rummage around, and if you find anything, you leave me some money or give me a ring with your credit card. Then you take the key back to the post office," said Christa Byrne, the co-owner, whom I met when I visited the island in September. "I don't want to deprive anybody of the bookshop if they want to go in."

Its titles are mostly British in theme: history, nature, cooking, guidebooks. There are used treasures, too. I bought a history of the Hebridean clans, a book about whisky smugglers, and "Lonely Colonsay: Island at the Edge," by Christa's husband, Kevin, whose many local roles include funeral conductor. ("Probably because he's the only one with a suit," she said.)

I had traveled to Colonsay by ferry from Islay, one of two ferry routes that service the island. Islay, a royal center in the medieval ages, is most famous today for the distilleries that produce distinctively smoky whiskies, such as Ardbeg and Lagavulin. It would bookend my five days of island-hopping, a journey that covered four islands in the Inner Hebrides, including one of the biggest (Mull) and two much, much, much smaller ones (Tiree and Colonsay). I highly recommend incorporating Islay into any visit to the Inner Hebrides, not only for the distilleries and history but also for the epic seafood platter at the Lochindaal Hotel pub. "Look at the claws on that boy! That's as fresh a lobster as you can get. You enjoy!" said Iain MacLellan, the fourth-generation owner and chef, when he set down the plate piled with langoustines, mussels, crab claws, scallops and, yes, a whole lobster.

The seafood platter at the pub of the Lochindaal Hotel comes piled high with langoustines, mussels, crab claws, scallops and a whole lobster. (Liza Weisstuch/For The Washington Post)

My journey would ultimately cover a great distance within the relatively limited expanse of the Inner Hebrides, which encompasses the southernmost 70-plus islands of the Hebrides and forms a crescent-shaped archipelago that hugs Scotland's southwestern coast. According to VisitScotland, 38 are inhabited to varying degrees. Some have a single store and church, others multiple villages. Most have ruins that tell stories of past civilizations.

Caledonian MacBrayne ferries would be my trusted guide - my amphibious guide, a saltwater stagecoach. A staunch urbanite such as myself might describe the ferry network as the subway of the sea, only with lounges - rooms with sofas, wood tables and tartan-patterned carpets. And outdoor seating for unparalleled scenery. And, of course, taighean beaga (read: toilets). There are also gift shops that stock books about history and whisky and CalMac-branded products such as clothing and toys. The Mariners Cafe, the cafeteria, sells very popular Scottish breakfasts. And most ships have a bar that serves "local whisky," a rather lofty offering in a region synonymous with prized single-malt scotches.

CalMac is owned by the Scottish government. It traces its origins to a shipping company founded in 1851. Today, there are routes to 54 ports and harbors on 35 islands and mainland cities across 200 miles of Scotland's west coast. In 2019, the fleet carried 5,686,042 passengers. Ferries are efficient and charming, if the weather abides. Sailings are canceled if the sea is too turbulent. Histories and poetry have been written about the region's arduous maritime conditions. Words from Charlotte Brontë's "Jane Eyre" are fittingly evocative: "Where the Northern Ocean, in vast whirls,/Boils round the naked, melancholy isles/Of farthest Thule; and the Atlantic surge/Pours in among the stormy Hebrides."

The risk of danger was low to none the Thursday I left Colonsay. I was standing with a beer on an upper deck of MV Clansman with James Truscott, a Scottish landscape architect and author of "Private Gardens of Scotland," and his wife, prolific island hoppers. We had met the prior afternoon in the sitting room of the Colonsay Hotel. He advised I carve out significant time to amble the 20-acre woodlands and gardens on the Colonsay House estate. Exotic plants grow there thanks to the warming Gulf Stream, he explained. Now I had a chance to tell him my visit was richer for meeting him.

It was a nighttime sail to Oban, a resort town on Scotland's west coast and home to CalMac's busiest port of call, a distinction that earned it the moniker "Gateway to the Hebrides." The bayside vista is a crescent of centuries-old buildings: towers, spires, domes and steeples.

There is a cinematic mystery and romance to sailing at night: The wind seems more determined, the sea is ink-black, and the islands' rock outcrops are shadowy silhouettes. Daytime sailing hints at adventure - and promises photos. The next morning's nearly four-hour voyage west to Tiree offered views of the ancient stone outcrops of Kerrera, an island (population: fewer than 50) across the narrow Sound of Kerrera from Oban. Less than eight miles west, the 13th-century Duart Castle on an eastern tip of the majestic Isle of Mull marks the approach to the Sound of Mull, which feeds into open waters strewn with land masses marked by manors or lighthouses. The ferry may have WiFi, but civilization feels millions of miles away.

The passengers that morning were largely athletic types. The luggage-storage areas were stuffed with oversize bags holding surfboards or tents. Tiree, the most westerly of the Inner Hebrides, is extremely flat and unreasonably windy. It's known as the "Hawaii of the North" and draws hundreds each October for the Tiree Wave Classic, the world's longest-running pro windsurfing competition.

John Kennedy Transport advertises "on-demand services," so I arranged for a ride to the hotel, not realizing it uses its buses as taxis. I hardly expected the giant blue coach that was awaiting me - and only me. It lumbered through Scarinish, the teeny port village with a market, a cafe, a bank, a hotel, a history museum and an old-timey phone booth turned community cupboard. We passed a memorial to the local men who left to fight in World War II and never returned. The island itself played a crucial part in the war; the Royal Air Force had a base here. Its soldiers monitored weather and dispatched the forecast that gave clearance for D-Day.

This was explained to me by Adam Milne, who owns the Reef Inn, which opened in May. He and his wife, Sian, built the sustainability-focused hotel, which sits amid a sweeping expanse of grasslands. She designed the interior, giving it a bright, clean-edged Scandinavian feel, a nod to Scotland's Nordic ties. It's all alabaster walls, pale wood furniture and floors, and potted palms. In the restaurant, tremendous windows overlook infinite stretches of sky. There's an electric-car charging point outside.

That afternoon, I met Ian Smith, an accordion player with the band Trail West, a Gaelic speaker and a history buff. In 2019, he and a bandmate started the Isle of Tiree Distillery in his late father's workshop. The raw, sepia-toned oceanside building has four small stills positioned in front of a window that faces west.

"Way out that way is Newfoundland," Smith said, motioning at the thunderous waves. "We're basically at the end of the world." He offered me a taste of bracing Tyree Gin, made with local sea kelp, a cash crop for the island in the 1700s, when the "brown gold" was sold to the mainland for glass and soap production. History looms in the whisky that's aging, too. In 1768, Tiree had about 50 distilleries. Most were operated illegally, and all were shuttered eventually. Ian's is the first to operate in 217 years.

Musician Ian Smith and a bandmate in 2019 opened the Isle of Tiree Distillery, the island’s first such legal business in more than 200 years. (Liza Weisstuch/For The Washington Post)

Tiree's notorious gale-strength winds were in full force the next morning. Rain was pelting. The ferry was late to arrive, and because of the sea swell, it was uncertain whether the boat would dock or turn around. I stood with other walk-on passengers in the Yellow Hare, a sweet bakery and cafe next to the parking lot. Vehicles were lined up to board - Toyotas, Mercedes, sporty SUVs, camper vans - all engines idle, everyone waiting to find out whether we would be leaving Tiree that morning.

Ferry travel is a great equalizer. There's no first-class cabin or exclusive dining option. Everyone shares every space and spectacular views. It inspires committed enthusiasts.

"There's nothing like the thrill of driving onboard, going upstairs, pulling out of harbor and steaming into the open seas," Alice Hickford told me. She's an administrator of Ships of CalMac, an online enthusiast group, and former merchant mariner. "There's nothing more exciting and daunting at the same time."

On any given sailing, you might find a family with kids playing cards across from a gaggle of napping backpackers. And over there, laborers headed to a month-long construction job on a remote island. On the next day's sail to Mull, I was regaled with stories by a man - a Tirisdeach (TIR-as-deich), or person from Tiree - who works on the crew of a ship that supplies lighthouses and services the vast system of buoys throughout the Hebrides. Many buoys, which serve as safe-navigation markers, are held in place with almost 500 feet of chain anchored to a five-ton metal sinker on the seabed below, he explained. As the boat pulled into the terminal on Mull, he pointed out a nearby ship, the floating workplace he would soon board.

Mull has about 300 miles of coastline and draws nature lovers for hiking in its dramatic inner mountainous landscape. Boat excursions to Staffa, a nearby island, offer the geological marvel Fingal's Cave and puffin sightings.

In Samuel Johnson's "A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland," a 1775 chronicle of his 83-day expedition though Scotland, he makes a fuss over losing his walking stick, a crucial tool to navigate the rugged terrain, on Mull. To him, the landscape of Mull evokes the "gloom of desolation." Mull is where I learned that walking sticks are cultishly popular objects. In a craft store at the bay in the village of Tobermory, the woman working showed me dozens of sticks with animal-shaped handles. The shop's owner carved them from antlers he collected in the woods. He sells them at agricultural shows throughout the Highlands; they are sought after by collectors.

But I was after craftsmanship of a liquid persuasion. Mull is home to the waterside Tobermory Distillery, which is situated on the bay in the island's capital village of the same name. Founded in 1798, it produces the assertively peaty Ledaig, the unpeated Tobermory and three gins. The pandemic temporarily halted tours, but you can get a sense of the stonewalled distillery's vintage grandeur through a towering window facing the road into the village around back.

I partook in a tasting that featured some limited-edition gems. A ruby-hued 12-year-old Ledaig finished in Amarone wine casks delivered lively cherry and smoked-plum notes. A dark-copper Madeira-cask-finished Tobermory smelled of incense and wood spice and tasted of almond paste and cherry jam. Visitor center manager Olivier MacLean, a native of Switzerland and former soldier, chronicled the distillery's long history: changes in ownership, sad shutdowns, triumphant revivals. "If these stones could talk ... ," he said, trailing off. Like the stones of so many very old structures throughout the Hebrides, they would tell a dramatic tale.

IF YOU GO:

Where to stay

The Lochindaal Hotel

10 Main St., Port Charlotte, Isle of Islay

011-44-1496-850202

This fourth-generation family-owned hotel features five charming en-suite rooms that have been recently refurbished. The low-key pub, a local go-to, offers an assortment of single-malt local scotches as well as more familiar selections. It's known for its epic seafood platter - a generous pile of crab claws, langoustines, scallops, mussels and a whole lobster - that must be ordered a day in advance. Stays include a full Scottish breakfast each morning. Rates from around $134 per night.

The Reef Inn

Kenovay Road, Crossapol, Isle of Tiree

011-44-7990-633953

The husband-and-wife team who opened this hotel in May have sustainability in mind. Construction was designed to minimize the hotel's carbon footprint, with measures such as underfloor heating, which requires lower temperatures to heat the building than a standard system. The decor is Scandinavian minimalism, the restaurant is classic bistro cooking, and the bar serves local gin. Open April to October. Rooms from about $175 per night.

Where to eat

Tobermory Distillery

Ledaig, Tobermory, Isle of Mull

011-44-168-830-2647

Established in 1798, this seaside distillery produces the assertively peaty Ledaig, the unpeated Tobermory and three gins. There are three tastings: a one-hour single-malt tasting that features four drams, offered daily at 3 p.m., about $28.50 per person; the half-hour Tobermory Gin Experience, which includes a sample of the three gins and a cocktail, offered daily at 11.30 a.m., about $24; and the Warehouse I Experience, which includes four drams pulled directly from the barrels and an engraved glass, offered daily at various times for about $54 per person. Distillery open Monday to Saturday 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. and Sunday noon to 4 p.m. Tours projected to restart in 2022.

Isle of Tiree Distillery

1A W. Hynish, Isle of Tiree

011-44-759-1005871

Started by local musicians in 2019, this is the first legal distillery on Tiree in 217 years. Tours, which include tastes of Tyree Gin or Hebridean Pink Gin, about $20 per person and must be scheduled in advance.

What to do

Colonsay Bookshop

Homefield House, Isle of Colonsay

011-44-195-1200320

colonsay.org.uk/shops-food/bookshop

This charming bookshop specializes in Scotland-focused titles about topics such as history, food and drink, and nature. The guidebooks selection is extensive. Christa and Kevin Byrne, who own the shop, also run a small publishing business focused on Scotland-centric books. Open Monday to Saturday 3 p.m. to 5 p.m. April through October or by appointment.

Information: visitscotland.com; isle-of-mull.net; isleoftiree.com; visitcolonsay.co.uk; calmac.co.uk