Metaphor: ReFantazio dares to ask if our democratic dream is merely that, a fantasy as impossible as a world of fairies and elves. (Sega)

Every election, we’re told we have to fight for democracy, how it’s the great “experiment,” almost like a mantra.

Is a civil, functioning democracy as much a fantasy as a world of magic, elves and fairies? This is the troubling question that drives this year’s smartest, most exciting video game, Metaphor: ReFantazio, from the developer Atlus and famed Persona director Katsura Hashino.

In Metaphor, player protagonist Will (or whatever you wish to be called) carries around his favorite novel everywhere, doting over it like a priest to prayer beads. The book describes a “fantasy” world - illustrated much like our own, with cars and skyscrapers - where “no soul is born into discrimination,” people choose political leaders based on votes, and “taking power or wealth by force is seen as the most shameful of transgressions.” Our fairy partner Gallica reads a few sentences and is taken aback at far-fetched concepts like equality.

“It’s strange to feel envious of a fictional world,” she remarks, speaking sideways to an audience seeking escape. But Metaphor is no mere escapist fantasy, nor is it nihilistic, unproductive political satire. Instead, it is an earnest plea for the audience to turn envy into action, anchored firmly in the harsh realities of governance over conflicting priorities and interests.

Metaphor begins with a king’s assassination that creates a power void, yet it doesn’t result in the usual bloody game of thrones. His death instead triggers a series of events that force the entire kingdom to adopt a democratic form of government, superseding his family lineage. It’s the populace, not blood or power, that will determine their leader. And Will, rebel and friend to the king’s cursed and comatose son, is roped in as a nominee. Metaphor is about the struggles of becoming president, or something like it. After all, the entire game is a metaphor.

Leon Strohl, left, and the elven Eiselin Hulkenberg, right, lead a diverse cast of characters. Diversity in Metaphor: ReFantazio is used to examine the challenges of meeting the democratic ideal. (Sega)

Complicating matters, Will is a member of the most marginalized race of people, the elda. In Metaphor, nine tribes of people are identified by their appearances and characteristics. Paripus, people with puppy dog ears and tails, are considered vagrants, while the horned clemar people populate the upper echelon. The game’s “United Kingdom” is splintered by class struggles kindled by those in power.

In development for around seven years, Metaphor was released just weeks before the close of the U.S. election. The timing felt cruel and deliberate, but it’s pure coincidence, director Hashino assured The Washington Post.

Like Will, Hashino carried books around for inspiration. Hashino’s Persona games are stylish, modern role-playing adventures starring Japanese high school students, so fantasy was new territory. He reread the usual fantasy staples by Tolkien. Crucially, he also read Plato and Socrates to absorb their views of a utopian world, as well as the works of Austrian psychologist Alfred Adler. Finally, he revisited “The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious” by Carl Jung, which heavily inspired the Persona series and the Archetype superpowers in Metaphor.

Will and his diverse followers inhabit Archetypes, which function as role-playing classes. Leon Strohl, an orphaned noble clemar, wields the warrior Archetype. These superpowers are awakened through metaphoric scenes depicting each character ripping a microphone out of their chest: literally speaking from their heart. Each scene comes after a moment of self-discovery fueled by moments of desperation. Will, Leon and the others all overcome their anxieties, the central emotional theme.

Katsura Hashino, director of Metaphor: ReFantazio and the Persona series. (Sega)

Hashino’s stories focus on the self and how we relate to others. Metaphor widens his lens to the broader populace, the strangers whose choices touch our lives. Hashino says the game is about the balance of turning one’s anxieties inward or projecting them onto others, authority figures such as politicians and religious leaders.

“If the striking of that balance is off, things could get out of control,” Hashino said. “We wanted to see how that balance between taking things on yourself and relying on others to face fear and anxiety could affect a story.”

Elections in the United States depend on not only projecting our fears and hopes onto candidates but also hoping that strangers will vote in the interest of others. Democrats struggled to communicate that the nation’s economy is healthy. It mattered little to voters who live from paycheck to paycheck faced with high grocery costs and unaffordable housing.

Don’t get it twisted: This isn’t a video game of discourse; it’s a traditional turn-based role-playing game that plays with Dungeons & Dragons fantasy archetypes. Will and his party still have to do battle with monsters, particularly mysterious, hideous invaders known only as “humans.” Yes, Metaphor is very playful with metaphors. You even have to fight other political candidates. The central villain, Louis, is a charismatic general who hopes to unite all races under the banner of strength, a variation of Will’s goals.

“They’re looking at the same materials but come to very different interpretations,” Hashino said.

Even the game’s music, composed by Persona’s jazz master Shoji Meguro, serves the game’s themes of unity. Atlus hired a Buddhist monk to chant lyrics to the game’s music, all written in Esperanto, the 19th-century invention intended to be a universal second language for the world. It is democracy and unity literally (not metaphorically) chanted as a mantra.

A nominee representing the race with the longest lifespans fights for “those too old to work.” He’s essentially attempting to create Social Security. As the game progresses, the real conflict becomes the fight to represent every tribe and their diverse interests.

“I don’t imagine this would turn out well in the real world,” laments the noble boy Strohl after reading Will’s novel. “In public opinion, tribal perspective always divides us.”

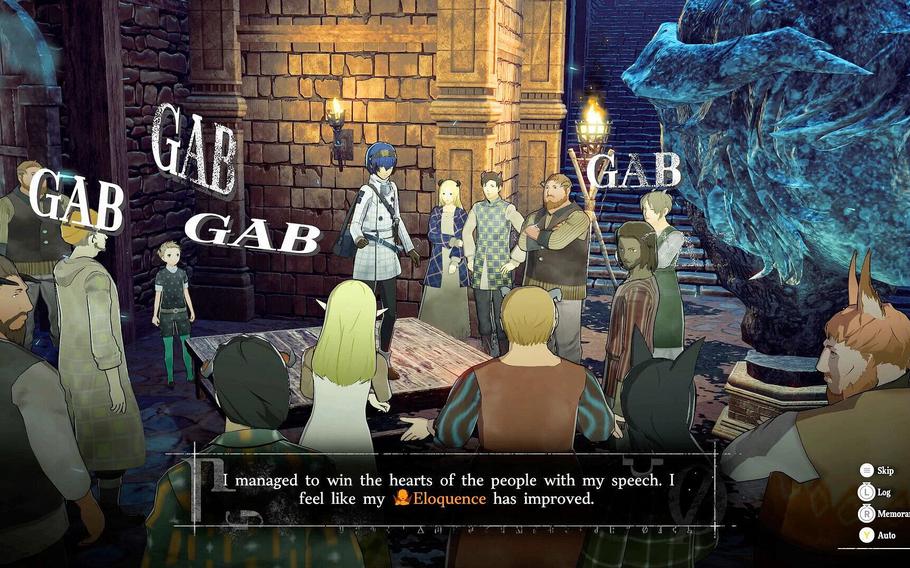

Public debate and speechmaking raise character aspects such as “tolerance” and “eloquence” as the player bids for the public’s favor in Metaphor: ReFantazio. (Sega)

Strohl’s words recall the kind of recent debates summed up in the 2022 book “The Great Experiment: Why Diverse Democracies Fall Apart and How They Can Endure,” by Yascha Mounk. Mounk covers how democracies have a history of religious and ethnic exclusion, how history’s most diverse societies operated under empires or monarchies, and how open elections invite demagoguery and demonization. Metaphor is keenly aware of this struggle.

“If everybody’s free to do what they want, they’ll work out their own reasons to be prejudiced,” says the dog-eared Fidelio after reading another passage from Will’s novel, his cynicism forged through oppression.

Like Metaphor, the novel’s idealism is meant as a flint for hope - a recurrent theme for Hashino. I asked him, “Why is it so important that this story was about hope, about fighting for a future we can only imagine?”

Hashino paused and put his head down in silence. He finally said, “To be honest, you asked a question that really hits the core. I’ve done many interviews, and I haven’t had a question like this.”

“Hope is progressing toward something undefined and undetermined by you or anyone else,” Hashino said after a few minutes. “I feel that is at the essence of all things.”

“Through this game, I wanted to make sure people aren’t confined in this story and world, ‘wasting time’ on a game. I want them to take something away from the experience, something that would help them reflect on their daily lives. … There are so many creations in the world that stimulate or move people. That in itself affects reality.”

Without the dream of a better future, how could it ever come to pass? Will’s friend and elven warrior knight Eiselin Hulkenberg says as much after she reads Will’s novel. Astonished at the book’s romanticism, she muses, “It takes power to walk the path of our dearest hopes.”

It is the mantra of the activist, to become a prisoner of hope. In this way, Metaphor is the perfect work to ponder and play amid the din of electoral bickering and consternation. It also helps that it’s a video game narrative filled with thrilling twists, betrayals and romance. Democracy can be more than just a fantasy story - and building it can be just as exciting.

Platforms: PC, PlayStations 4 and 5, Xbox X/S

Online: metaphor.atlus.com