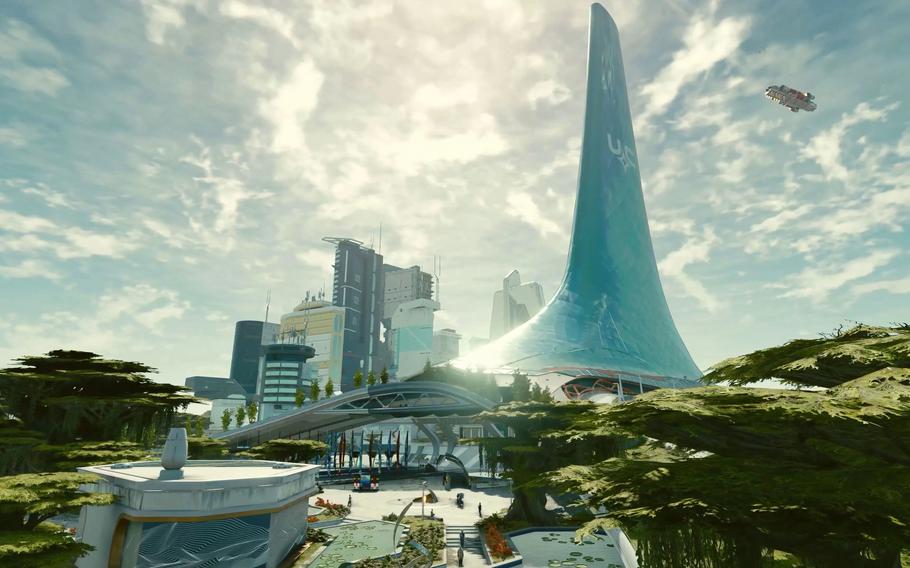

In Starfield, players can follow a central quest or explore a vast number of planets with unparalleled freedom as they embark on an epic journey to answer humanity’s greatest mystery. (Bethesda)

As a story and as a game, Starfield is about ambition: how technology serves humanity, but also the humanity we lose in service of technology.

A monumental 10-year project by Bethesda Game Studios and Xbox's great hope after a decade of struggle, Starfield is a marvel of planning and engineering. A video game with a thousand explorable planets shouldn't exist, yet here it is in 2023. It fills that grand scale with a familiar narrative structure: There's a central quest that acts as a guided tour through the game, and hundreds of other side paths, including factions to join that provide unique questlines.

But this is still a Bethesda game, and there are sacrifices. The studio's last single-player game, Fallout 4, famously sacrificed many role-playing conventions in favor of a satisfying, repeatable action game loop of scavenging and crafting in service of a power fantasy. Conversations felt linear, the range of outcomes narrow. Starfield does not do this. Instead, it is the studio's best attempt to marry satisfying action game mechanics to an open-ended adventure that responds to player input. The shooting and action feel great, but this game's biggest challenges pose questions with huge consequence. One questline had me determine the fate of thousands of people. It's a power fantasy beyond the gun. It's about a player's ability to analyze situations and make decisions based on experience and retained information, and it's a theme that persists after the credits roll.

After 40 hours of play, the galaxy still feels so big it’s hard to feel a sense of residency and community. (Bethesda)

But in making a game as big as Starfield, the studio sacrificed a sense of intimacy they once mastered. Gone is the majesty of approaching something from a distance, like the walk in Fallout 3 toward Washington, D.C., the National Monument a lone beacon in the nuclear-demolished skyline. After 40 hours of play, the galaxy still feels so big it's hard to feel a sense of residency and community as I did in Whiterun of Skyrim.

The greatest mystery of Starfield's long development was how players would navigate to, from and on planets. For the people of this 24th century, lightspeed travel is as easy as calling an Uber. In practice this nonchalance affects the player, too - to sometimes deadening results.

Much of playing Starfield is dealing with a cascade of maps and locations. It's all done via the classic gaming convention of "fast travel." There is no seamless transition between planets and atmosphere - in fact it feels as if the game asks that you travel through the seams. There are gameplay sequences cleverly designed as menus and copious (but mercifully fast) loading screens anytime the scenery changes, from orbit to surface, from outside to inside. It's jarring to find an ancient alien artifact deep with the core of a planet at the very edge of the galaxy, pull up a menu, click through to the main population hub of New Atlantis and seconds later find myself in my character's living room. It's not possible to fly in orbit around a planet, nor can anyone punch through its atmosphere. Starfield is missing a sense of environmental cohesion.

Starfield offers hundreds of planets with distinct, handcrafted stories within full-blown communities. The game contains many large cities and space stations with believable, busy crowds. (Bethesda)

The game tries to introduce a core cast of characters in Constellation, a group of explorers dedicated to finding these artifacts in the hopes of answering humanity's oldest and most urgent questions, such as the existence of God. They are all distinctive and written well, but our interactions stretched hours apart. I eventually viewed them less as crew members of my ship and more like storage mules for the thousands of pounds of garbage I accumulated and gave them so I could build more weapons and spaceships.

If this feels harsh so far, it's only because Bethesda games are barely games, and closer to experiences. It's like asking me to write a review about a neighborhood after living there for the total sum of two days. After 40 hours, I was still discovering planets with distinct, handcrafted stories within full-blown communities. Yes, the player's movement is incredibly disjointed through the game's many parts, but that's all in service of detail rarely matched in any entertainment medium. If a corporation in this game has a building, it doesn't just make room for the CEO or lobby. The game will populate several floors for this company, going as far as architecting offices for a human resources department.

Past Bethesda worlds take place in barren fantasy or post-apocalyptic settings. Starfield scales up effortlessly to large cities and space stations with believable, busy crowds. Passerby conversation may point to more quests. The near-future setting allows Bethesda to play with modern story archetypes. Yesterday's thieves guild questline is tomorrow's exploits in corporate espionage. Quests big or small hold many surprises. A simple coffee errand could become a matter of life or death.

The game is also flexible enough to provide a more solitary experience. If a player chooses to land anywhere outside of a planet's handcrafted points of interest, the game will produce a "tile" of explorable land and populate it with smaller, procedurally generated quests and locations. Each landing site feels as large as a single, past Bethesda game, and the game can create thousands of these instances. Quiet exploration may be interrupted by a ship landing in the distance, and it's always a question of whether they're friend or foe.

When it comes to central storylines, this is easily the best Bethesda quest yet. Its premise may seem mundane as a hunt for magical space rocks, the same MacGuffin plot device that drives most popular science fiction and fantasy today, from Marvel to Zelda. But Bethesda uses this as an opportunity to tell a diverse anthology of adventures. It tells parables of how space travel has affected the way people communicate and congregate.

After the credits roll, Starfield cleverly plays with the concept of the “gameplay loop,” the design philosophy that keeps players returning to a game. The structure of the entire game encourages you to stay, explore more, or maybe do it all over again. (Bethesda)

When I worried the game's side content relied too much on shootouts, one main quest story gave me several hours of talking, planning and debate with other characters. Another story literally changed the scenery around me in a blink, as the game takes advantage of the fast-loading capabilities of current-generation hardware. It finally gave me a chance to get to know my Constellation crewmates as people, even fall in love with one of them. When Starfield started to feel alien, its main storyline reminded me of humanity's ancient and sometimes dangerous yearning for purpose.

It's impossible for me to summarize the entirety of the experience because I haven't experienced it all. But from what I've seen, there's a sense of playfulness in highlighting human behavior that doesn't change despite it all. A spaceship passing by may hail urgently only for you to realize it's a 24th-century telemarketer asking about the warranty on your ship. The option to destroy it is appreciated. Starfield is a distinctly American vision of humanity's future where the English language dominates and capitalism is mightier than ever. More familiar forms of communication are so outdated, a ship signaling Morse code for help ends up terrifying the neighbors.

The game's most astonishing achievement comes after the credits roll. Starfield cleverly plays with the concept of the "gameplay loop," the design philosophy that keeps players returning to a game. The structure of the entire game will begin to unfold, and it encourages you to stay, explore more, or maybe do it all over again.

Starfield is the most technically sound release in the studio’s famous history of massive, bug-ridden worlds. (Bethesda)

It's hard not to compare the excitement around Starfield to 2020's Cyberpunk 2077. That game by CD Projekt Red was also developed in great mystery for a very long time, and seemed to promise a living cyberpunk city that doubles as virtual residence. While awesome in its own right, Cyberpunk 2077 failed in ways Starfield does not. Bethesda is good at making these worlds. This game's marketing says you can spend all day roleplaying as a space pirate or an interplanetary sheriff, and Bethesda made good on such promises. There are so many more experiences I've yet to discover. The ones I've found are at least as good as past Bethesda adventures.

Starfield is the most technically sound release in the studio's famous history of massive, bug-ridden worlds (it even performs well on the weaker Xbox Series S console). But it's also a game so big, it can account for only so much. It's all a convincing illusion, yet it remains fascinating when that illusion breaks. It's the tried-and-true dichotomy of living in a Bethesda game world.

One key scene I experienced underscores the challenge of Bethesda's technical ambition. My astronaut, "Captain Gene," was witness to an event that defies time and matter, something the human mind may never grasp. It's the culmination of thousands of years of human achievement and curiosity. Ten paces away from me, his lover, Barrett, had only one thing to say. "Hey friend, let's chat sometime, okay?"

I'm sorry, what? I responded to him anyway. He gave me an "alien sandwich," and said nothing else.

In my real-life living room, the illusion shattered and I laughed hysterically and slapped my knees. No other type of game does this. Other big-budget games would take great pains to animate this scene with motion-capture actors, cinematography, a swelling, well-timed musical score and a script.

But a Bethesda game, with all of its coding talent and Microsoft money, would forgo all that pomp and circumstance just to give me the agency to drag my lover across the galaxy to the most important discovery in human history just so he could make me laugh and give me food.

The technology may fail, but the human experience as a messy, impetuous thing remains. Because of that, Starfield makes the right sacrifices.

Platforms: PC and Xbox

Online: bethesda.net/en/game/starfield