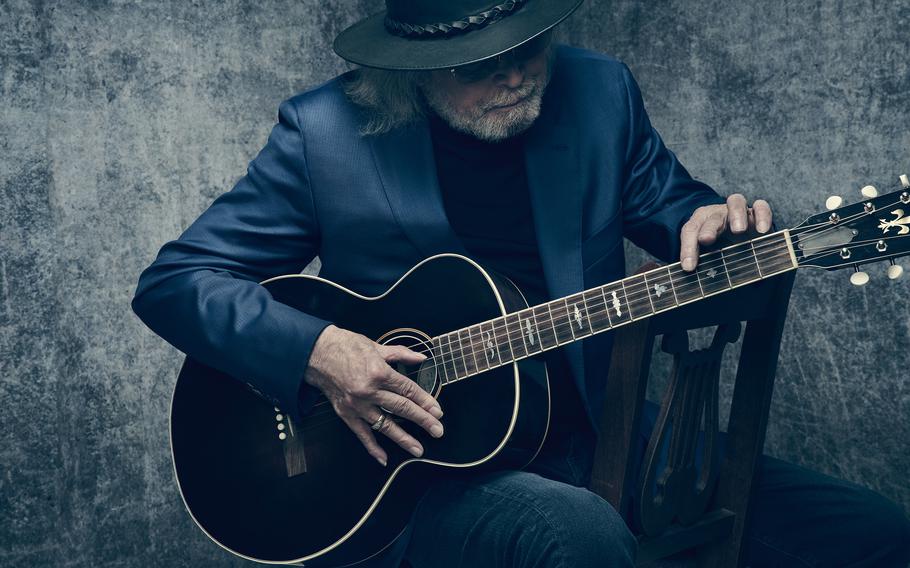

“My dream was to get people I admire to sing our songs,” Barry Gibb of the Bees Gees said. Gibb is among this year’s Kennedy Center Honors recipients, the eldest and last of the English-born, Australian-raised Gibb brothers, the contributor of that haunting vibrato and the principal architect of their singular sound. ( Marvin Joseph/The Washington Post)

MIAMI BEACH — Understand that the music was everywhere, icing turntables, electrifying strobe-lit clubs, flooding the radio dial when radio was everything, commanding valuable real estate in our brains, an earworm with an indelible disco beat.

“Saturday Night Fever,” the double album including other artists but dominated by the Bee Gees, wasn’t merely the soundtrack to that movie with those lush three-part harmonies and all those hit singles: “Stayin’ Alive,” “How Deep Is Your Love,” “Night Fever,” “More Than a Woman.” It was the soundtrack to the late-1970s, six consecutive No. 1 hits equaling the Beatles’ record, five simultaneous songs in the top 10, two years boogieing atop the charts and 25 million copies sold before the decade’s close.

The leonine-locked Bee Gees, in second-skin slacks and navel-slashing shirts, became a prime example of the law of celebrity gravity: Anyone that big will be taken down, polyestered casualties in the war on disco. To the brothers, the moment was so personal, sustained and painful that it was referred to as “The Backlash.”

This fall, Barry Gibb, 77, sat in his ducal South Florida home sipping microwaved sake from a souvenir coffee mug.

“If you have too much success, people are not happy with you,” he said without a tinge of sadness, more as a statement of fact. In a lengthy afternoon interview, Gibb was relaxed, candid and prone to humility, possibly due to the Australian aversion to bragging — the “tall poppy syndrome,” which stipulates that anyone too boastful will be sliced down to size.

But respect has a tendency to return with age. Sir Barry since 2018, Gibb is among this year’s Kennedy Center Honors recipients, the eldest and last of the English-born, Australian-raised Gibb brothers, the contributor of that haunting vibrato and the principal architect of their singular sound. Twins Maurice and Robin died, respectively, in 2003 and 2012.

It’s reductive and wrong to view the Bee Gees in solely a “Fever” state, though the album tends to loom over everything like a massive disco ball. It’s even proved lifesaving: “Stayin’ Alive” is among the songs whose beats match the rhythm for performing hands-on CPR.

But disco only encompasses one of the group’s iterations.

“We were just inclined to work in different styles,” Gibb said. The brothers, and Barry in particular, produced three sustained acts of extraordinary musical creativity beginning as teenagers in the early 1960s.

A performer since age 9 who quit school five years later, Gibb seized the cultural moment, becoming one of the most successful songwriters of all time, with 220 million albums in sales, according to the Guinness World Records, second only to Paul McCartney.

“We didn’t really have a category. If we enjoyed something, we wrote it,” Gibb, whose most recent album, “Greenfields: The Gibb Brothers’ Songbook Vol. 1” (2021), features a constellation of country and Americana greats singing with him, said. His name and artistry are laminated on almost every Bee Gees’ gem, including the wrenching “How Can You Mend a Broken Heart,” immortalized by Al Green, and “To Love Somebody,” covered by Nina Simone, Janis Joplin (at Woodstock) and, well, everyone. “There’s a light/A certain kind of light/That never shone on me.”

An inspired guitarist, Gibb became the master of moving on.

“We’ve got to be able to have success with other artists because that’s what the future is for us,” he told Maurice and Robin after the “Fever” fallout when they weren’t getting radio play. “We couldn’t be teenage idols all our lives. That wasn’t going to work.”

Barry, did you enjoy being a teen idol, selling out venues packed with adoring teenage girls? “Oh, yeah. Are you kidding?” he sighed.

“You’re selling golden eggs and you know he’s the goose,” said Bee Gees producer Albhy Galuten by phone.

“It was obvious that he was the leader of the group in about five minutes in terms of his actions and songwriting skills,” said album engineer Karl Richardson in a separate phone interview.

Gibb, Galuten and Richardson are credited with creating the “Saturday Night Fever” sound.

“He was always courteous, never raised his voice,” Richardson said, even when conditions were challenging — and the French chateau (Elton John’s “Honky Château”) where they began working on “Fever” was “a nightmare,” he recalled. “The recording studio was horrible.”

As for songwriting, Gibb equates it to “a barrel full of thoughts. I would just jiggle around and look for another title,” he said. Melody first, then the beat, finally lyrics tailored to the sound, in that order. “All I had was my imagination. I emptied my mind and allowed it to come in.”

It’s estimated that Gibb wrote or co-wrote more than 1,000 songs, though he’s never kept count. Why bother when you’ve delivered dozens of golden eggs?

“Grease?” Gibb. “To Love Somebody?” Check. “Guilty?” Guilty. “Islands in the Stream,” “How Can You Mend a Broken Heart,” “Nights on Broadway,” “I Just Want to Be Your Everything,” the last for younger brother and teen heartthrob Andy who died in 1988 at age 30. Yes, yes, yes, yes.

“My dream was to get people I admire to sing our songs,” Gibb said. He didn’t have to ask twice. Gibb displayed a particular talent for writing for women. Name a diva, she came courting: Dionne (“Heartbreaker”), Diana (“Chain Reaction”), Barbra (“Guilty,” “Woman in Love”), Dolly (“Islands in the Stream,” with Kenny Rogers) and Celine (“Immortality”).

Fellow Kennedy Center Honors recipient Dionne Warwick initially balked at “Heartbreaker,” which spent five months on the charts. “I didn’t feel it was my kind of song. It didn’t feel good to me. I was sort of bullied by both Barry and [record producer Clive Davis]. I relented,” she said by phone. “He did it very softly, and in a very gentlemanly manner.”

Barbra Streisand, famed for her desire for control — “Usually when I’m recording, I’m 100% hands-on,” she noted in an email — surrendered. “The easiest album I’ve ever made and, to my surprise, it was also one of the most commercially successful ones I’ve ever had,” she wrote. “Guilty” and “Woman in Love” also spent five months on the charts, Gibb responsible for two of her five greatest hits.

“Barry could not only resonate with Barbra but empathize and connect with her,” Galuten recalled. “He knew it viscerally. He was an emotional empath. He could intuit what would move singers emotionally.” In the studio, “he doesn’t like to confront people, but he doesn’t give in.”

In another regard, it didn’t matter who interpreted Gibb’s work.

“From many of the backing vocals, it’s so clearly a Bee Gees song. There’s no question who wrote ‘Islands in the Stream.’ It’s cut from that cloth,” said engineer John Merchant, who worked with Gibb frequently.

He compared “Fever” to an illustrious work in a museum, akin to the “Mona Lisa,” and “in that same building are all these other wonderful works of art that you breeze right by them. It distracts from the other work that in some ways is more interesting.”

Gibb sits in the massive house “Fever” bought. It’s where he raised five children (four sons, one daughter, like his birth family) with his wife Linda, Miss Edinburgh 1967. They met in the grooviest Sixties London way imaginable at the BBC’s “Top of the Pops,” where Linda was a presenter.

“I was supposed to go on to compete in Miss Scotland but he happened,” she said. Maurice and Robin long lived nearby on the same street, creating a South Florida Gibbsian enclave.

Each room is outsize, ornate, bursting with bibelots. The dining room, punctuated with plastic gating for the dogs, appears unused since the mid-1980s.

Gibb recently broke a toe, hence he hobbles around in socks — yet he won’t use the house elevator. He spends much of his time lounging in his man cavern, the once-formal living room lined with guitars, piled with books, and the adjacent, alleged sun room that admits not a ray of natural light.

The gazillion-dollar Biscayne Bay view, the very reason nascent nabobs dream of someday residing here, is perpetually blocked by drawn papal-red drapes, which make it easier for Gibb to spend his days watching YouTube music videos.

His office is plastered floor-to-ceiling with framed gold and platinum albums, but he ran out of wall space. There are numerous Grammys, including Grammy Legend and Lifetime Achievement awards, as well as other honors of all sorts, many stacked on the floor. His desk, once owned by Bing Crosby, is crowned with a trio of gladiator masks from the Ridley Scott epic.

“Reminds me of me and my brothers,” Gibb said, clad in athleisure wear and a baseball cap. “We had incredible moments mixed with crises, arguments. Just what brothers do.” In 1969, the group briefly disbanded when Robin wanted to perform on his own.

Barry Gibb grew up in hard circumstances after World War II, the son of a bandleader and a mother who worked multiple jobs. They moved to sunny Australia during the government’s postwar immigration drive to increase population. It was there that Gibb and the twins started performing and writing songs.

Hugh Gibb was stingy with praise.

“He was non-demonstrative and he was aggressive,” Gibb said. “If we did a great show, our father would say ‘Great audience.’ He would never say to us, ‘Great show.’ In other words, don’t get too used to it.”

Gibb can seem uncomfortable about his wealth, even thrifty, the residue of growing up with so little and despite his business savvy and success in controlling the publishing gold mine.

“He’s led a rather unpublic life for someone this successful,” said his eldest son, Stephen, a musician. “He doesn’t want to buy into all the hype. I think he worries it will affect his ability to continue.”

The brothers’ initial success in the United Kingdom was stunning, defying probability and logic, worthy of a biopic. One is in the works with Graham King, who produced “Bohemian Rhapsody” about the band Queen. Gibb wrote a song for the movie, his first in years, while penning a memoir.

Who should play young Barry? Gibb said, “I don’t know but he better be pretty.”

On this subject there is no debate: Barry was very pretty, the bee’s knees of the Bee Gees.

On Feb. 7, 1967, the Gibbs returned to their native England after traveling five weeks by sea from Australia, their home of nine years. The first record Barry heard was the Beatles’ 45 “Strawberry Fields Forever” with “Penny Lane” on the B side. Seismic: “I remember thinking, ‘Oh, my God, we might as well go back.’ How can you compete with that?”

A little more than two weeks later, the Bee Gees met and signed with Robert Stigwood, a showman of the P.T. Barnum variety. They went into the studio the following month. Their first London concert appearance occurred at the end of March. By May, they had their first British hit, “New York Mining Disaster 1941.”

In July, the brothers released their first international album, “Bee Gees’ 1st.” In 1967 and 1968, the group recorded the classics, “I’ve Gotta Get a Message to You,” “To Love Somebody,” “Words” and “Massachusetts.”

“We made three albums in the space of a year,” Gibb said. “Once you got momentum, you had to keep going.” The hits kept coming. Stigwood was as given to flattery as Hugh Gibb: “After about five hits, I said, ‘Have we made it?’ And Stigwood said, ‘I’ll tell you when you have made it.’ And he never did.”

Gibb deployed his now-famous falsetto on 1975’s “Nights on Broadway.” Record producer Arif Mardin suggested he try it as “cherry on the cake.” Though the tremulous effect was parodied by Jimmy Fallon and Justin Timberlake on “Saturday Night Live” — a good sport, Gibb joined them once — singing that high “feels and always felt really powerful,” he said.

Said Galuten, “He had so much control with his voice. He could hit anything. He was always in tune. His meter was incredible.”

Gibb was capable of composing in the studio, in the dark, on the fly, with kids and cartoons blaring in the background, in a matter of hours and with merely a prompt. The songs for “Saturday Night Fever” were created without seeing a script or reading the original magazine story that served as its basis.

In 1978, Gibb’s phone rang. Stigwood needed a song for a movie he was producing, a hit song because that’s what Gibb delivers. There’s no script. There’s barely an idea. In the beginning, there was only the word, and the word was “Grease.”

“Well, how do you write a song called ‘Grease?’” Gibb recalled. “The only way to do it is as a slogan”: Grease is the word/It’s got a groove, it’s got a meaning/Grease is the time, is the place, is the motion/Grease is the way we are feeling.

He was at home, watching the kids.

“I watched my father write that song in real time, pick up a guitar while I’m watching Bugs Bunny,” his son, Stephen, recalled. His father wrote it in an afternoon. “It’s like he’s an antennae. He knows that one frequency where all those things hang out.”

For years, Gibb didn’t comprehend how the mid-1970s lean years before their triumph on the dance floor, followed by the backlash to its triumph, would get him to this point: the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1997 with his brothers, and now the Kennedy Center Honors long after they’re gone.

“But I’ve come to terms with that because I don’t think you can be successful if you don’t fail,” he said. You wait it out. The crowds come back. “Greatest night of my life,” Gibb said of performing in the 2017 “Legends” slot at the Glastonbury Festival, a 75-minute set in front of more than 100,000 people.

As he told his brothers, “If you’re just a group and you make records, you’re not going to survive. You’ll have your time, and then you’re done.” Even if you’re huge, even if you’re the Bee Gees.

“Build a reputation as songwriters,” he advised. “And you can live forever if you do that right.”

The Kennedy Center Honors will be broadcast Dec. 27 at 9 p.m. on CBS and stream on Paramount+.