()

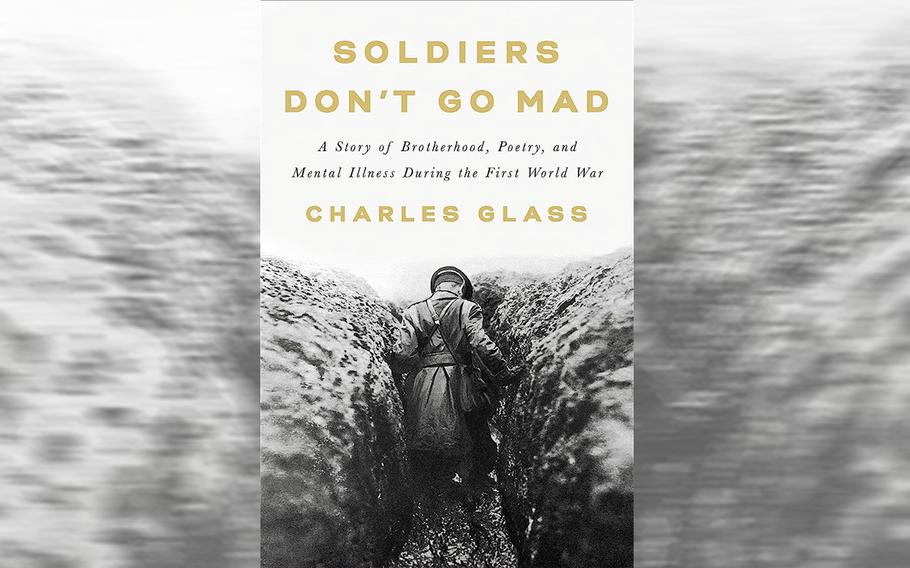

Charles Glass’ masterful work “Soldiers Don’t Go Mad” dispels the notion that post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, is a modern phenomenon of the “woke” generations.

The book, by former ABC News correspondent who covered wars in the Middle East, Africa and the Balkans, explores the lives of young British army officers who fought in the trenches in World War One. They were brought to Craiglockhart War Hospital outside Edinburgh after their minds and spirits were shattered by the horrors of trench warfare in World War One.

Instead of PTSD, their condition was described at the time as “nervous disorders” or “shell-shock.” Their wounds were sometimes dismissed by top British commanders as cowardice but were as real and debilitating as a shattered limb or machine gun bullets in the gut.

Despite lingering ignorance and hostility to the soldiers’ agony, senior British commanders had no choice but to take psychological wounds more seriously.

Nothing could prepare young soldiers for what to expect when World War I erupted in 1914. More than 40 years had elapsed since war between France and Prussia ended in 1871 – the most recent major continental conflict.

Instead of glory, the soldiers found a terrifying world of high explosives, flamethrowers, machine guns and poison gas never before seen in warfare. With the conflict at a standstill for years, troops were huddled in rat-infested, rain-drenched trenches and underground bunkers without adequate food and ammunition.

Under such conditions, 10 percent of the officers and about the same percentage of enlisted men suffered mental collapse. The high commands of both sides were desperate for ways to rehabilitate experienced soldiers and send them back to the slaughter.

Still, not everyone in the British establishment understood the reality of PTSD or how to deal with it. One of the patients, Siegfried Sassoon, was sent to the hospital despite no visible symptoms, such as uncontrolled shaking, bouts of weeping or inability to focus.

However, Sassoon, from an upper-class, politically connected family, had become an outspoken critic of the war and the politicians who ran it. Rather than court-martial a decorated combat veteran, whose near-suicidal courage earned him the nickname “Mad Jack,” the brass sent him to a mental hospital in hopes he would change his views.

At Craiglockhart in Edinburgh, Scotland, patients received experimental treatment considered routine today – including therapy, dream analysis, hypnosis and hobbies – but which were revolutionary in an era when mainstream doctors favored electric shocks, ice baths and suppression of traumatic memories.

Doctors were conscious of triggers that might bring back the horrors of combat. The administration convinced Edinburgh city fathers to suspend the daily cannon firing at Edinburgh castle because of the effects on patients who were encouraged to visit the city.

Social mores of the early 20th century British class system required separation of officers and enlisted soldiers. Officers were sent to Craiglockhart. Enlisted patients were farmed out to conventional mental hospitals, basically “lunatic asylums,” or simply discharged.

Some patients recovered enough to return to combat or light duty far from the battlefield. Others never did.

Ironically, the Craiglockhart doctors modeled their treatment along techniques they learned as students in Germany and Austria, the very countries that Britain was fighting but which had pioneered research into diseases of the mind.

The book is not only a tale of war and resilience but one that explains the wave of pacifism that swept Europe in the years before World War II and complicated diplomatic efforts to curb the rise of Nazism in Germany.