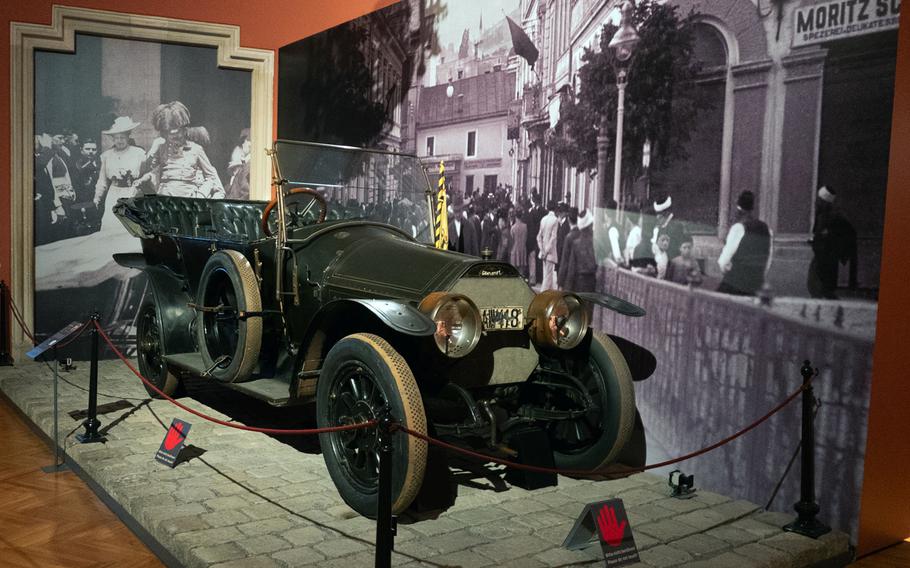

Vehicle in which Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, June 28, 1914, Museum of Military History. (Alan Behr/TNS)

I arrived at last at Vienna's Hotel Sacher 18 months late, with three Pfizer injections on my record and with relief for having finally gotten from there to here with body and spirit intact. I had postponed this business trip just days before the pandemic had sealed the borders as completely as might war. But here I was, lounging at a true Viennese breakfast, spoon-feeding myself the hotel’s signature pastry, Sachertorte, and washing it down with the house sparkling wine.

The staff delivered to my suite the three parcels I had sent to myself just before the lockdown began: a still-needed package of surgical masks, a box of German-to-Italian language flashcards (for future adventures) and, most important, the long-awaited three-piece, single-breasted dark gray worsted suit from my London tailor, Henry Poole & Co.

I had only recently spent long months variously either at liberty in a desolated Manhattan or quarantined, at once growing a beard and then shaving it off after my middle schooler said it made me look like an unemployed platypus. While staring with mannered enthusiasm into Zoom-coddled screens, I had not worn socks or shoes, let alone a bespoke suit cut by the tailors to Dickens, Disraeli and Churchill. And yet here I was, at breakfast in a grand hotel patronized by royalty, celebrities and the merely rich, looking quite the part. Only a paroled embezzler could have felt so implausibly grand.

The Hotel Sacher belongs to the Leading Hotels of the World, which recently opened the Leaders Club rewards program to members for free — and that explains how I got involved in a therapeutic treatment in the hotel’s spa that involved being coated in a chocolate cream that leaves your skin baby-bottom smooth. Afterward, it was time to get serious, after a fashion, with a visit to the Museum of Military History (its slogan is “Wars belong in a Museum”). It holds what I consider the most important automobile in history: the boxy, olive-green Graef & Stift convertible in which the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand, the heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was seated when, in June 1914, he and his wife, Sophie, were fatally shot by a South Slav nationalist. That set into motion the chain of events that led to World War I and, in a dotted line, most of what followed in European history for the remainder of the century.

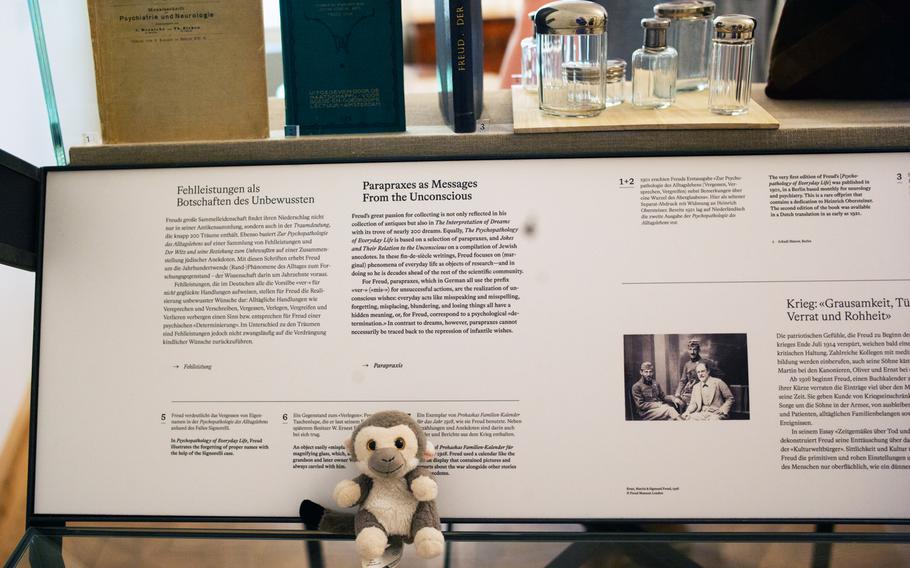

Dawn brought a fresh round of Sachertorte and sparkling wine, which may sound even more therapeutic than a spa, but I doubled down on all that with a visit to the recently renovated and expanded Sigmund Freud Museum. The museum is set up in the apartment, famously located at Berggasse 19, that had been both the office and residence of the founder of psychoanalysis. The exhibition spaces now encompass the living quarters and the office, and you can start your personal tour from either direction and take yourself through rooms containing videos explaining Freud’s contributions. You'll also see some of his personal artifacts, ranging from his initialed doctor’s bag to a vitrine filled with selections from his prized collection of antiquities. The displays in the surprisingly airy and sunlit rooms are sensitively labeled in German and English.

It was a compelling way to engage as a tourist with the style of therapy with which I grew up. (Talking through your troubles was considered therapeutic until, in this century, it was replaced by shopping and litigation.)

I recalled that, on my first visit to Vienna decades before, I had called my grandmother and told her that when she had lived in Vienna as an adolescent, her apartment was a five-minute walk from Freud. “Grandma,” I asked her, “Why didn’t you go? It would have done you some good.” I visited her former building now, and as with so much in the historic districts of Vienna, the facade had hardly changed.

Sigmund, a well-traveled comfort monkey, in the museum of the home of his namesake Sigmund Freud. (Alan Behr/TNS)

Vienna in my grandmother’s time was renowned for its intellectual and artistic vigor. It was possible, at Cafe Central, to run into Dr. Freud, the pioneering Zionist Theodor Hertzl, the novelist Stefan Zweig, a young Leon Trotsky (already plotting to overthrow the Czar) and an even younger, resentful Adolf Hitler (already twice rejected admission to the Academy of Fine Arts). I refreshed myself there with a Grosser Brauner (analogous to a double espresso), which in Vienna is always served with Leitungswasser dazu (a glass of tap water on the side).

Sculpture of the poet Peter Altenberg (1859-1919), a memorable regular, Cafe Central. (Alan Behr/TNS)

As Grandma would have done, I spent the evening at the Volksoper for a German-language performance of the classic musical "My Fair Lady." Used here in place of the cockney dialect that the main character, Eliza Doolittle, was trained to put aside in both the distinctly Shavian play and its lighter musical adaptation was a thick Viennese dialect that I strained to follow. But both the translation and the production worked on all accounts.

With Austria being both the home and key exporter of many of the world’s great chefs, it was natural that I would see a variety of food at an indoor-outdoor gourmet festival, held at a refined Italian Renaissance concert hall, the Kursalon Huebner, in the Stadtpark (city park). My personal favorite find: a made-to-order marzipan see-no-evil monkey, from the local patisserie and confectionary maker Oberlaa.

I met with Robert Pukenhofer, who has done what in Vienna is highly respected: He carried on an important Austrian tradition. He has revived the watch brand of Carl Suchy & Soehne, once watchmakers to the royal family — and to Dr. Freud. The design of his first watch, the appropriately named Waltz No. 1, references the work of the Austrian modernist architect Adolf Loos. As I have repeated in legal texts, “brand is story,” and the skilled relaunch of Carl Suchy rides skillfully upon that essential point. The wristwatch is both contemporary and respectful of its history, as is the table clock that the brand launched the day after my departure and that Mr. Pukenhofer kindly showed me in sneak preview.

Robert Putenhofer of Carl Suchy & Soehne with historic pocket watch and images of the new Waltz No. 1 watch. (Alan Behr/TNS)

It had to happen, even in Vienna, but the business portion of my visit began the next day and it kept me fully occupied for the duration. Fortunately, one of my contacts suggested lunch at the sun-filled Steirereck, a restaurant in the City Park that, under the direction of Chef Heinz Reitbauer, holds two Michelin stars. I had a split fillet of lamb from the restaurant’s own farm and, for dessert, Java coffee — a chocolate pastry bordered by foam and garnished with coffee sauce. My colleague had Wiener schnitzel, the signature dish of Vienna that is on the menus of both the city’s great and humble restaurants but that here was done to Michelin-star standards, with fluffy bread crumbs surrounding perfectly cooked milk-fed veal.

Although I try to avoid indulging in two gourmet meals in one day (Tums tourism, I call it), this would be my last night in town, and it would all have been incomplete for me if I did not, as I typically do, have my final dinner at the Rote Bar (Red Bar) in the Sacher. Despite its name, it is a full-service restaurant featuring Austrian cuisine — and home to some of the most enjoyable dinner piano music anywhere. The meal started with hearty venison and mellowed into a selection of house-made sorbet scoops. And that was it for Vienna — but not quite.

Mindful that I had once rerouted my air travel to avoid missing a final breakfast at the Sacher, I left plenty of time for it now. The hotel delivered to me the Sachertorte I had purchased for the trip home (packed, per tradition, in wooden boxes). They were loaded into a spare shoulder bag I had brought for the purpose, and it was goodbye Vienna for now.

I suggest that, when planning your trip that Vienna, you keep in mind that it is four times the size of Paris and nearly as populous. Indeed, the breadth and unapologetic grandeur of Vienna can be a surprise to new visitors: It is a former imperial capital in a small country more familiar in North America for earthy Alpine charm (which is real but happens at the other end of Austria). In short, whatever time you think you need for Vienna, add at least one more day or you may come away feeling you had cheated yourself.

However much the pandemic may, out of necessity, momentarily dampen the party-hearty Viennese spirit, it was delightful to see that fully on display once more. The new attitude, both optimistic and practical, is that science has accomplished what it can for now; let’s pop a cork as we would have done before and get on with life. To go where you like in town, you do need to show proof of vaccination or a recent negative test and wear a medical-grade mask. But this is Vienna, where Europe has long come to talk, drink, eat, play Mozart, bathe in chocolate and maybe plan a revolution. And so it happily remains.

The nave of the Stephansdom, the cathedral of Vienna. (Alan Behr/TNS)

Websites

Hotel Sacher: www.sacher.com or www.lhw.com.

Steirereck im Stadtpark: www.steirereck.at.

Cafe Central: www.cafecentral.wien.

Museum of Military History: www.hgm.at.

Sigmund Freud Museum: www.freud-museum.at.

Volksoper: www.volksoper.at.