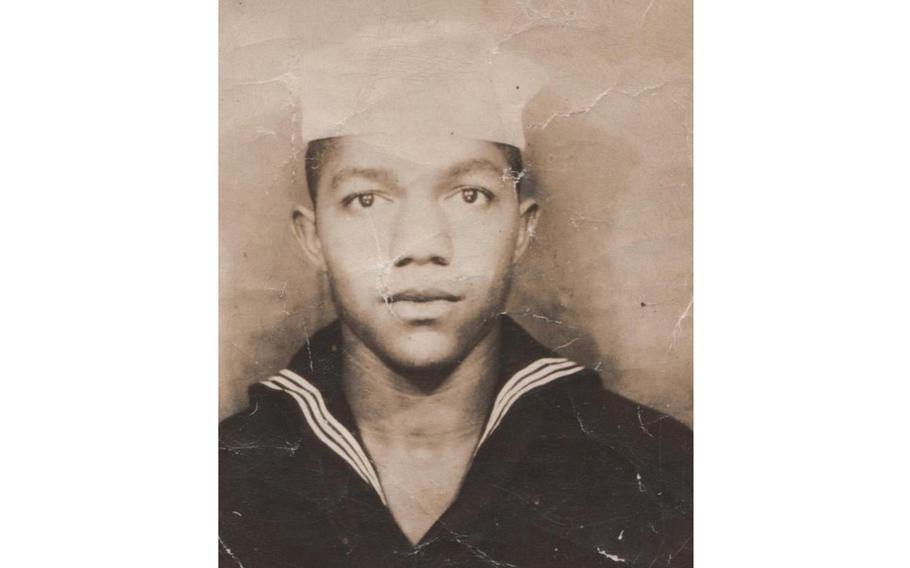

When torpedoes struck his battleship, Neil Frye was just 20 years old — a country boy halfway around the world from his tiny hometown of Vass, North Carolina, caught off-guard on an infamous day. (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency)

(Tribune News Service) — When torpedoes struck his battleship, Neil Frye was just 20 years old — a country boy halfway around the world from his tiny hometown of Vass, N.C., caught off-guard on an infamous day.

He had joined up at 19, signing on as a mess attendant in a segregated branch of the Navy, serving aboard the USS West Virginia, which carried him all the way to Pearl Harbor.

When the Japanese attacked that morning in 1941, he was likely below deck in the mess hall, serving breakfast until the first torpedo rocked the ship. Six more torpedo blasts would follow, along with a pair of bombs.

And though the crew fought to keep their battleship from capsizing, it sank into the Pacific harbor and killed 106 on board — including Frye.

For decades, the 20-year-old’s remains went unidentified, buried in Hawaii alongside other unknowns. But in September, a modern DNA analysis finally rescued Frye from historical uncertainty. In December, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency announced the identification. And in April, he will return to North Carolina to rest with fallen veterans.

“It’s just amazing,” said his niece, Carol Frye Davis, who lives in Moore County. “It’s excitement. It’s a funeral — true, indeed — but it’s more of a memorial. We’re not going there to mourn.”

To hear the family tell it, Frye joined up at 19 to follow his big brother, Russell. He came from a family of five boys and five girls — all confined to a share-cropping life in Jim Crow North Carolina.

So Frye followed his big brother Russell into the Navy, far from the farm.

“It was nothing for a Black man to move forward with,” Frye Davis said. “They wanted to get their mama her own house.”

Struggle on board

Frye hadn’t been in the Navy long before he found himself at Pearl Harbor, so the family knows little about his shipboard life.

But on Dec. 7, 1941, the torpedoes knocked two large holes in the West Virginia’s hulls, and oil fires from the nearby USS Arizona spread to its decks, according to Defense Department accounts.

The surrounding destruction was so intense that the West Virginia’s commander died of a shrapnel wound from an explosion on another battleship.

While the ship sank, another mess officer named Doris “Dorie” Miller not only carried wounded sailors but also manned the ship’s anti-aircraft guns and shot down a plane. For this, Miller became the first Black sailor to receive the Navy Cross.

The battleship listed about 20 degrees to port while the fires raged, as described in survivors’ accounts, but the crew struggled to prevent flooding and it sank straight down. Salvage crews recovered the West Virginia, which was repaired and returned to service.

But 35 men recovered from the wreck would go unnamed.

Modern analysis

The drive to identify Pearl Harbor casualties came largely from one of its survivors, Ray Emory, a Navy gunner who survived the attack, according to his profile from the University of Washington.

Thanks to his pressure, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency began to disinter the unknowns, including 35 from the West Virginia in 2016.

The agency’s laboratories examined more than 200 DNA samples from more than 2,000 bones, leading them to their first positive ID: New Jersey sailor Angelo Gabriele, who returned home for a military funeral in 2019.

Frye Davis said she never expected to hear much out of the investigation. Her family often joked, “He just didn’t want to come home to Vass.”

When they heard the news, her first thought was a wish that “Grandma Bell” had still been alive to discover what happened to her boy.

“Somehow,” Frye Davis said, “she already knew.”

On April 3, Frye, who earned a posthumous Purple Heart, will finally receive the same honor due him more than eight decades. He will be buried at Sandhills State Veterans Cemetery in Spring Lake, just outside Fort Bragg and very near Vass.

©2025 The Charlotte Observer.

Visit charlotteobserver.com.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.