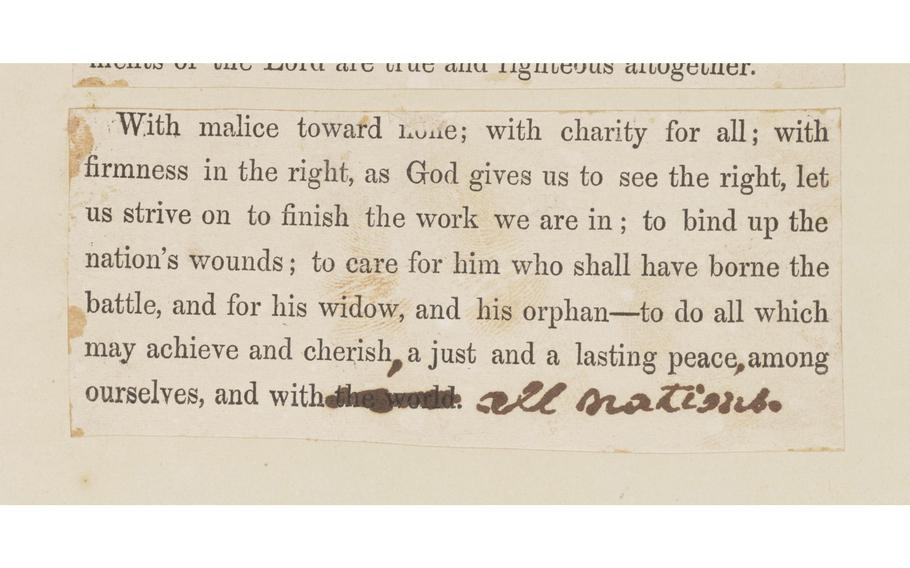

This famous paragraph from Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, delivered March 4, 1865, bears what might be his fingerprints. (Library of Congress)

When Abraham Lincoln was preparing his speech for his second inaugural in 1865, historians think he cut the sentences and paragraphs from a printed draft and pasted them onto the copy he planned to read from.

An excellent orator, he adjusted the spacing, apparently for cadence and dramatic effect.

Experts think that as he worked, he may have gotten ink or glue on his fingers. And when the final paragraph was pasted, the one that begins: “With Malice toward none; with charity for all,” he might have left two partial fingerprints on the famous passage.

It’s a smudge that has intrigued historians.

“We don’t have proof” that Lincoln did the cutting and pasting, said Michelle Krowl, a Civil War historian at the Library of Congress. But Lincoln was so meticulous, “there’s almost nobody else” who could have.

As the nation approaches the second inauguration Monday of President-elect Donald Trump, it also nears the 160th anniversary of Lincoln’s historic second inaugural, and the speech that would be hailed as one of the best ever given by an American.

Trump is among more than a dozen presidents to be elected twice, but only the second, after Grover Cleveland, to be elected to nonconsecutive terms.

Lincoln’s second inaugural came in the waning days of the Civil War and produced a speech that is carved in stone at the Lincoln Memorial.

The historic document from which he read is kept at the Library of Congress, not far from the U.S. Capitol, where inaugurations take place.

The speech is noted for its majesty, and for the unusual cut-and-paste way Lincoln assembled it — a process that also may have left us the fingerprints.

Library experts have known about the prints for years and have examined them closely for clues. But history probably will never know their source for certain.

“Our problem is, with any of these questions about whose fingerprints are on the document, we don’t have” a verified sample of Lincoln’s fingerprints for comparison, Krowl said.

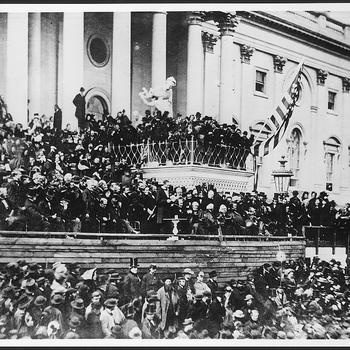

The speech was delivered on March 4, 1865, outside the grand, columned east entrance to the Capitol. Lincoln addressed a crowd of about 40,000 people on a blustery, rainy day that gave way to sunshine.

The Civil War, in which more than 600,000 people died over almost four years, was soon to be over. American slavery was ending. And parts of the South were devastated.

Lincoln wanted to address what had happened and why, and find some meaning in the tragedy that was still unfolding.

“Lincoln wrote for all time,” Ronald C. White Jr. wrote in his 2002 book “Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural.” His address was “the prism through which he himself strained to see the light of God.”

Lincoln biographer Michael Burlingame called it “the greatest of his oratorical masterpieces.”

Lincoln wondered about the reasons for the war:

“If God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword … it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’”

He was a careful and intelligent writer who composed his speeches himself and was obsessive about punctuation, Krowl said: “He loved commas.”

Using a pen, he apparently added what appear to be numerous new commas to the pasted-up reading version of the speech. But he also changed several other commas to semicolons.

He may have worked on rough drafts. “When he knew he was to present an important speech, he toiled far ahead,” White wrote.

Eventually he penned the address on lined paper and had it printed.

The Library of Congress also has the handwritten version. There are what appear to be partial, if less visible, fingerprints elsewhere on the reading version and handwritten document, said Julie Biggs, senior paper conservator at the library.

“There are fingerprints really throughout,” she said in a video interview Thursday.

The cut-and-paste version seems to have other partial prints, which look like they’re from glue, she said. One appears on the speech’s first paragraph, which begins: “FELLOW COUNTRYMEN.”

But examination of the last paragraph under special illumination suggests those prints might have been made with ink on the fingers, rather than glue, she said.

“Not definitive,” she said. “But … more likely.”

When Lincoln got the printed copy, historians think he cut it with something like a razor into more than two dozen segments.

They think he used the smelly glue of the time to reassemble them in two wide columns on a heavier piece of paper he folded down the middle to make his reading copy.

“If we’re imagining that scene in our minds, Lincoln has that final paragraph,” Krowl said. “At this point he might have glue on his hands.”

As he presses the paragraph onto the page, the substance on his fingers might have left the prints, she said in a video interview Wednesday.

Krowl said she noticed the prints about two years ago while preparing for a presentation. She was zooming in on a digital image of the speech. “I happened to be looking at that paragraph … and I thought, ‘Wait a minute. I think those are fingerprints,’ ” she said.

Shelly Smith, head of book conservation at the library, said in a video interview that other experts there have been aware of the prints.

“It’s very likely that other conservators in previous years have noted there are fingerprints,” she said.

Lincoln’s cut-and-paste process looks imperfect elsewhere in the speech. One sentence, “The prayers of both could not be answered — that of neither has been answered fully,” seems glued crookedly to the page.

So does the sentence “Fondly do we hope — fervently do we pray — that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away.”

At his second inauguration, Lincoln stands before a white table, center, outside the U.S. Capitol. (Alexander Gardner/Library of Congress)

It was an address for the ages.

The speech was short — just over 700 words. Lincoln, who was 56, spoke slowly. Even so, the address probably lasted only six or seven minutes, White wrote.

Lincoln thought it was a good speech.

“I expect [it] to wear as well — perhaps better than anything I have produced,” he wrote to a supporter in New York. “But I believe it is not immediately popular.”

Krowl said the library was given the original versions of the speech by the children of Lincoln’s secretary, John Hay, in 1916.

On the back of the last page of the handwritten version, Lincoln wrote:

“Original manuscript … presented to Major John Hay. April 10, 1865.”

Four days later, Lincoln was shot at Ford’s Theatre by John Wilkes Booth and died the following morning.