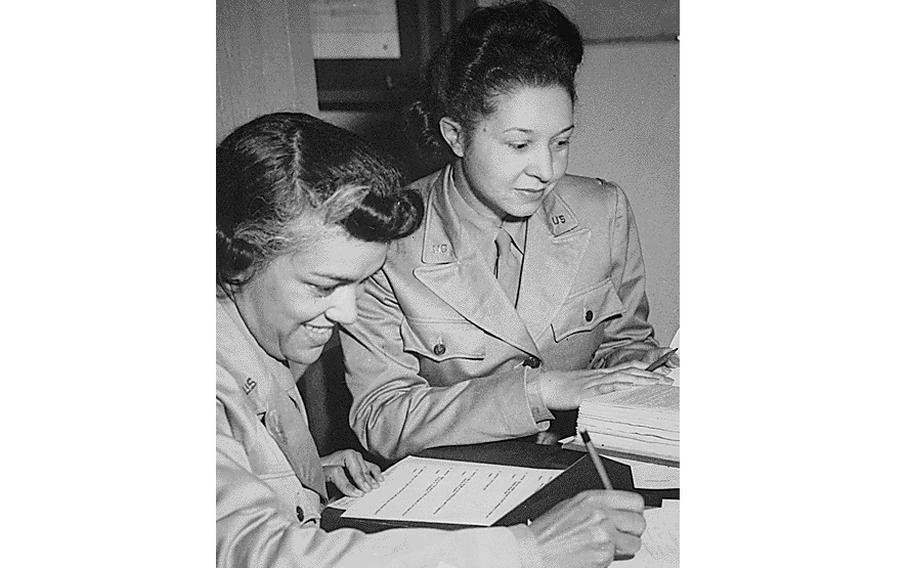

Harriet West and Irma Cayton go over their recruiting schedule report. (National Archives via The Washington Post)

According to most official accounts, Georgia Watson did not exist.

As part of a highly secretive Army unit, composed almost entirely of women responsible for defending D.C. against an air attack, Watson had been instructed to say nothing to anyone about her unit.

“We did not exist on paper, had no table of organization, and could officially be issued nothing,” she wrote years later in her memoir. The unit was known only as Battery X.

Although Battery X did not exist on paper, its work was very real.

In mid-1942, Gen. George C. Marshall, the Army chief of staff, personally directed the Army to handpick several dozen women for a classified assignment: evaluating whether women could be successfully integrated into D.C.’s antiaircraft artillery units.

When the women reported for duty in late 1942, Americans were on edge. A year before, the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and the Japanese rout of American holdings in the Pacific had rattled the nation.

Residents on the East and West coasts installed blackout curtains, painted their windows, and dimmed the lights in the evenings. Air raid drills were commonplace, and civilian patrols kept watch in towers dotting the outskirts of major cities.

Months of German U-boat attacks in the Atlantic, some of them alarmingly close to the East Coast, reinforced the sense that the United States might again come under direct attack. Watson and the women of Battery X trained to ensure that the Axis Powers never got close enough to try.

The idea of using Army women to guard the nation’s coasts was born of necessity. Marshall, the American commander responsible for allocating Army resources during World War II, faced an acute personnel dilemma in 1943: He needed more men to fight abroad, more men to defend the homeland, and more men to build weapons — and he was running out of them fast.

But on a serendipitous visit to England, Marshall stumbled on a solution to his manpower crisis: women.

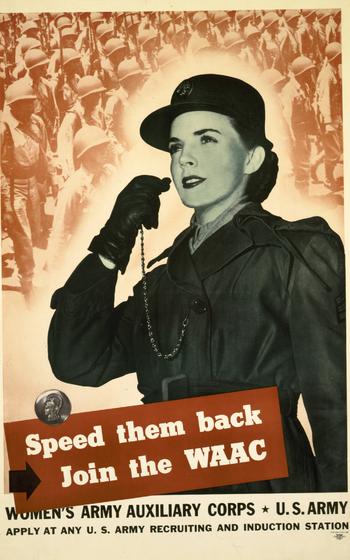

After seeing the effectiveness of the British women defending England from attack in the Auxiliary Territorial Service, Marshall quickly realized that the women signing up in droves for the U.S. Army women’s program — then called the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC) — could be used in the same way.

A recruiting poster for Women's Army Auxiliary Corps. (Library of Congress via The Washington Post)

Marshall knew the experiment would be controversial. Even though hundreds of thousands of women were donning military uniforms by 1943, none of them had been authorized to help operate heavy weapons. He needed to be sure women could do the job. But if they failed, no one could know they had tried.

Watson understood that discretion was paramount. “The gun batteries defending the Capitol would be used in the experiment and their location rated the highest classification,” she wrote, adding that “public attitudes toward the use of women in combat positions also made it necessary.”

The lack of recognition, however, did not stop Watson and her colleagues from doing their jobs. Military women in World War II were there to serve.

Elna Hillard joined the WAAC one month after it was established. Her first assignment was to oversee Battery X’s training, and she got to see the unit’s performance up close. During one drill, she wrote in a memoir, the male colonel responsible for timing the exercise was dumbfounded when her crew matched the speed of the best crew in the entire command.

“Impossible,” he said.

Assuming there had been an error, the colonel asked the women to do the same task two more times. They found the target just as fast.

When explaining what made the women so effective, Hillard said that they were willing to make small, creative changes that had a big effect on the outcome.

For instance, rather than follow the standard practice of intentionally overshooting the target by a wide margin and then walking this distance back, the women almost never overshot on purpose. Instead, Hillard said, they got as close as they could on the first try, and then patiently zeroed in on the target in small, deliberate increments.

In this way and countless others, the women of Battery X proved they could do the job — and do it well.

“We got no medals, no commendations, no news releases,” Watson wrote, “nothing but the private satisfaction of proving to ourselves that we could keep our mouths shut and do a job. Any job.”

Despite their sterling performance during training, the women of Battery X never got the chance to operate guns over Washington. By the time they had completed their final qualification exercises — and passed with a near-perfect score — the threat of air attack had receded. Army planners shifted their focus to Europe, and the women moved on to their next assignments.

Eighty-two years later, the memory of Battery X has nearly vanished. The women involved in the experiment, like Watson and Hilliard, have died; and, with no official record of the unit, there has been little public acknowledgment of Battery X’s trailblazing work. All that is left of their service are a handful of short memoirs.

Before the unit disbanded, however, there were a few moments of quiet recognition. When, in 1943, Rep. Harold Cooley (R-North Carolina) accused the War Department of endangering Congress by defending the capital with wooden guns (they were decoys), Congress sent the chair of the Senate Special Committee to Investigate National Defense to Hillard’s office to inspect the unit.

When the chairman, then-Sen. Harry S. Truman (D-Missouri) arrived, Hillard remembered that he peppered the unit commander with questions. As former artillery officer himself, Truman understood the ins and outs of air defense and insisted on a comprehensive overview from Hillard’s superiors.

Ultimately, Truman walked away from the briefing satisfied with the men — and women — defending Washington.

“Excellent organization,” Truman said. “I feel safe now.”

Lena Andrews is the author of Valiant Women: The Extraordinary American Women Who Helped Win World War II and an Associate Research Professor at the University of Maryland’s School of Public Policy.