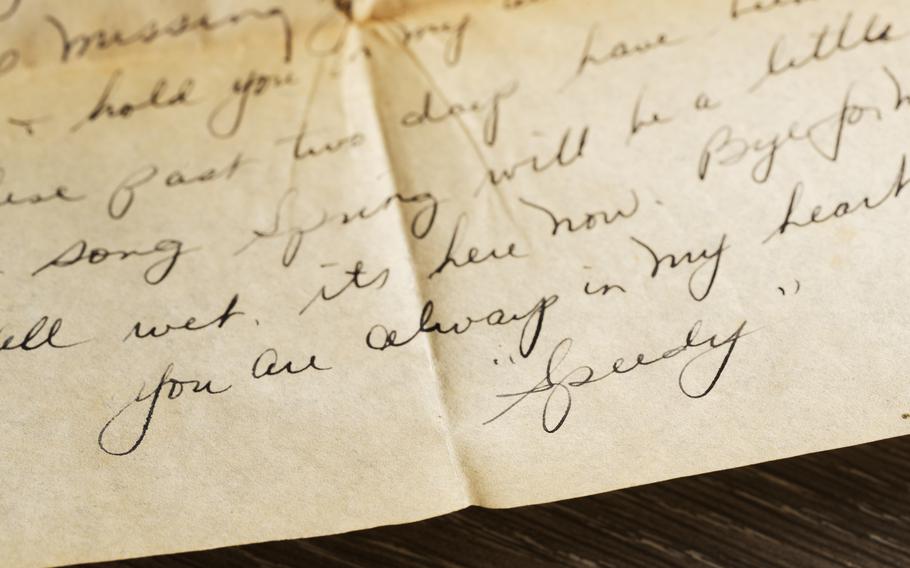

A letter from soldier Louis “Speedy” Weber to his wife, Frances, who was back home in New York. (Craig Hudson for The Washington Post)

At 5 p.m. on June 9, 1942, Louis “Speedy” Weber wrote his first wartime letter to his wife, Frances, who was at home in the Bronx. He had enlisted in the Army that day. But he hadn’t gotten far. He was eating in an Italian restaurant nearby before leaving.

“Darling,” he wrote on a restaurant post card. “Being shipped to Fort Dix. I am writing this during my supper time. Excuse the card. … Love Speedy. Will write tomorrow.”

He got to Fort Dix in New Jersey that night and wrote Frances on June 10, “I want you to get word from me every day.” She almost did. He wrote her again on June 17. And again on June 19. His letters kept coming — from South Carolina, North Africa, Sicily, France, Belgium, Germany.

In total, Weber wrote more than 300 letters to Frances at 1517 Jesup Ave. She saved them all.

In 2022, the fragile and discolored letters were given anonymously to the USO, the Arlington, Va.-based nonprofit that offers hospitality, entertainment and support to service members.

Now the organization is sorting and digitizing them while trying to piece together the couple’s story.

Archivist Michael Case handles letters from Weber at USO headquarters. (Craig Hudson for The Washington Post)

“I’ve never seen anything like it,” said USO archivist Michael Case. “It’s incredible.”

The letters offer a window into the private life and intimate thoughts of one young soldier away from his wife as his Army engineer unit fought the Nazis across North Africa and Europe.

Weber was barred from writing military details by the Army censors who read all his mail. But his personal life went uncensored, and his handwriting was excellent.

“I always said that I didn’t care if the world knew how much I love you,” he wrote in one letter. “Well now the whole damm Army will know.”

“Just as sure as night must follow day I’ll keep missing you until I can come home and hold you in my arms once again,” he wrote in another letter. “You are always in my heart.”

And in a letter written from North Africa, he said: “Be good and when this thing is over we start where we left off by being so happy that people will envy us.”

Their exchanges were also sometimes intimate, so much so that she joked that she might get pregnant just reading his racier letters. (His letters often repeated the contents of hers, which are lost.)

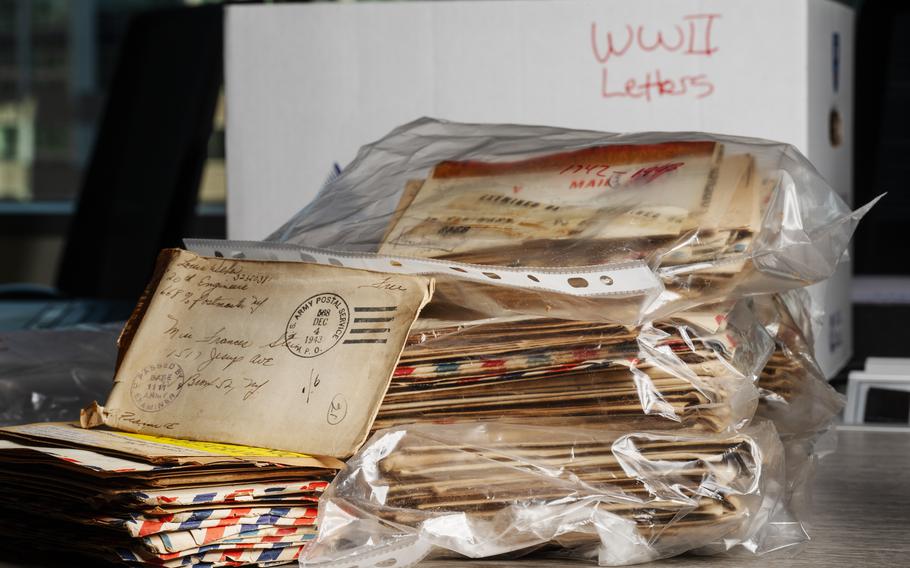

Weber wrote more than 300 letters to his wife. They were anonymously donated last year. (Craig Hudson for The Washington Post)

In a 1944 letter written from Germany, he wished Frances herself might be sent over in a package. “I’ll just leave the rest to your imagination,” he wrote.

The large number of Weber’s letters is not unusual, said Megan Harris, research specialist with the Veterans History Project at the Library of Congress.

Given that World War II service members were away for years, and many wrote home almost daily, they often generated hundreds of letters, she said in an email.

“We have about 75 letter collections … that include over 300 original letters,” she said.

Case said the source of Weber’s letters is murky. They were delivered anonymously to a USO office in New York, perhaps because several letters are on USO stationary. The letters, some of them bundled in frayed string, made their way to Case in the USO’s Arlington headquarters in December 2022.

He said he has not yet read all of them.

Little is known publicly about the lives of Weber and Frances. They apparently had no children, and it’s not certain whether they have any living relatives.

In 1950, the U.S. Census lists them still on Jesup Avenue, living with Frances’s widowed mother, Rose.

Frances was working at a Post Office. Weber was described as a watchmaker.

Decades later, they were in Sunrise, Fla., outside Fort Lauderdale, when they died, according to brief newspaper death notices. Weber died at 78 on Feb. 19, 1997. Frances died at 87 on Feb. 24, 2005. They are buried together in a cemetery nearby.

Weber was 23 when he went off to war in June 1942. Frances was 24. They appear to have been married for about a year, according to government records. They were of modest means. In one letter, he reminded Frances that he was “broke” when they met.

Both were the children of immigrants, Census records show. Her parents had come from Austria in the 1890s. The Census listed their native language as “Hebrew.” Her father was a tailor.

His parents were from what is now Ukraine, according to his mother’s naturalization petition. His father was a longshoreman.

In 1940, the families lived about five blocks apart on the same street, according to the Census.

Weber’s letters are being archived at USO headquarters in Arlington, Va. (Craig Hudson for The Washington Post)

His letters show that Frances frequently wrote back. One of her letters was nine pages long. But none of her letters were in the batch given to the USO.

“It’s very frustrating,” Case said in a recent interview. “Maybe they exist somewhere.”

She also sent him packages — salami (“it sure was good”), anchovies, gum, Ritz crackers and a sweater.

Once, he sent her a message on a primitive disc recording. “If you want to hear what I’ve got to say, put it on the phonograph and listen,” he wrote. The record’s whereabouts are unknown, Case said.

They also talked politics.

In the 1944 election, she was for the Democratic incumbent Franklin D. Roosevelt. “The way you were rooting for Roosevelt I wouldn’t be afraid to bet that you would divorce me if I told you I voted for [Republican challenger Thomas E.] Dewey,” he wrote. (Roosevelt won.)

Weber sent her pictures and some French money. He had a photo of her, which he said he showed so often that people would be able recognize her on the street. He mentioned that she had freckles. No pictures of them were included in the donation.

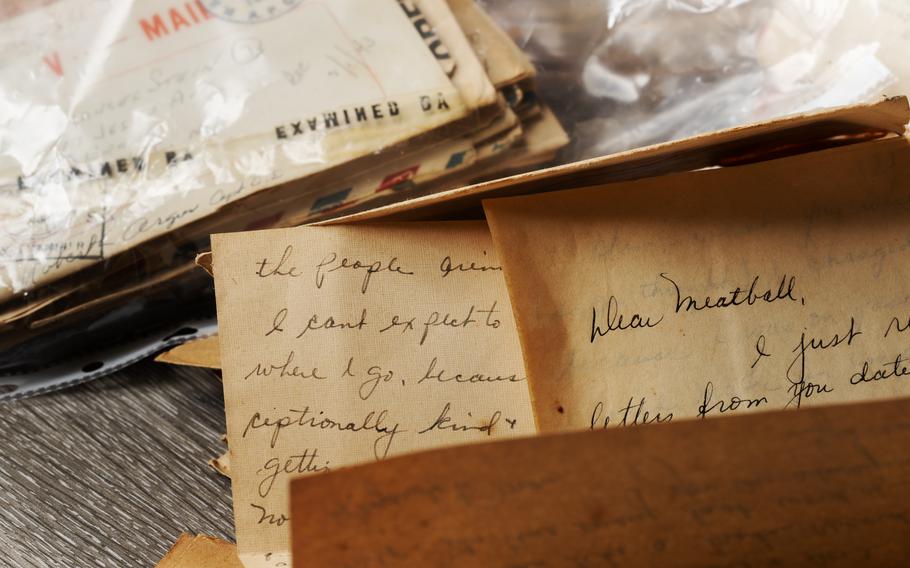

In his letters, Weber called his wife pet names, including “meatball.” (Craig Hudson for The Washington Post)

Their banter went back and forth through the mail. He teased her, called her “Miss La Rue,” “Meatball,” and “girl of my dreams.” One of his letters has a fingerprint on it.

She called him “Mr. Life of the Party” and criticized his spelling, which bugged him.

“I’m so mad,” he wrote from Germany in 1944. “I know very well that you didn’t mean to hurt my feelings but it so happens that you did. … I’m not fortunate as you when it came to brains. I guess I must have missed the boat.”

The next day he felt better. “Yesterday I wrote you a pretty sarcastic letter,” he said. “And today I’m back to normal again.”

It’s not clear what his job was in the service. He was in two Army engineer units and served in North Africa, Sicily and northern Europe.

He mentions several of the Army’s major battles, but does not detail any role he might have had.

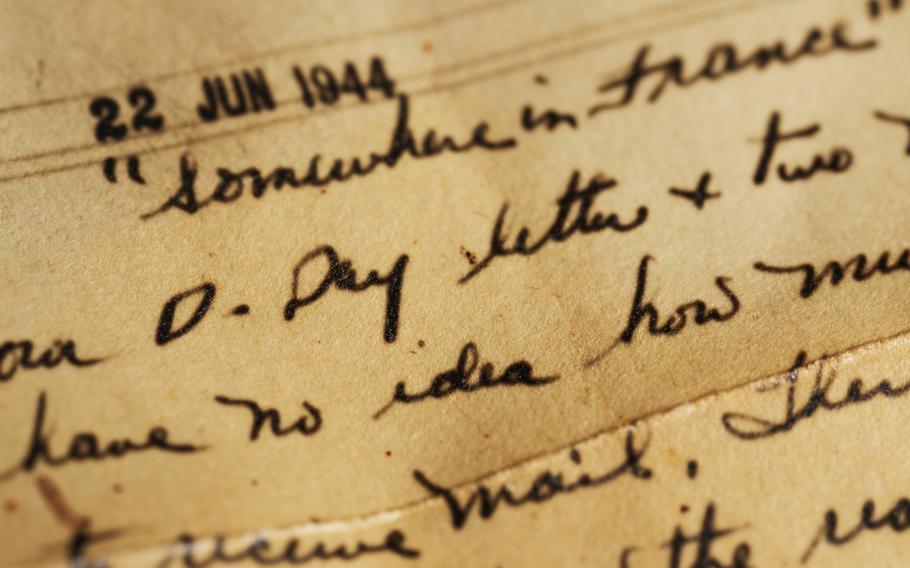

On June 21, 1944 he wrote from “somewhere in France” about the D-Day invasion two weeks earlier.

“There must have been plenty of turmoil June 6,” back home, he wrote. “I could just see everyone who has someone or somebody in the forces over in England start hoping and praying that their loved ones were alright.”

On Jan. 10, 1945, he wrote Frances about the Battle of the Bulge, the weeks-long winter battle in which Nazi forces smashed through the American lines in Belgium and Luxembourg and were eventually forced back. The battle was just ending.

Referring to an anxious letter from her, he wrote from Belgium to assure her that he was okay.

“I could see in the way you wrote that you were worried,” he said. “I can’t blame you. … The news headlines must have been shocking and a foot high when the Germans broke through our lines.”

“I must admit that things were kind of tough then, but everything is O.K. now,” he wrote. “Darling I wish you wouldn’t worry every time something happens. In case any thing should happen to me, you’d be the first one to know about it.”

“So don’t forget, no news is good news,” he wrote. “I love you. … Speedy.”

One of the last wartime letters he wrote was on July 4, 1945. It was penned on Nazi stationary used by a Hitler school where Weber was staying.

The war in Europe had been over since May. “They won’t be using this particular type of letter head,” he wrote. “So I decided I’d use a little of it.”

“Bye for now, baby,” he wrote. “Remember, I love you and you only. … You are always in my heart, Speedy.”

Alice Crites contributed to this report.