Archivist John Deebin looks at pension case files from the American Revolutionary War on Thursday, Nov. 7, 2024, in Washington in the East Research Room at the National Archives. (Eric Kayne/Stars and Stripes)

Mary Linville spent 36 years in nursing, but her passion has always been history.

Now retired, she’s begun digging into Revolutionary War pension files, where she uncovered the story of her fourth great grandfather, a member of the Maryland militia who was wounded twice during the Battle at Guilford Courthouse in North Carolina.

“I can only imagine the hardships he overcame and sacrifices he and other soldiers made to the cause of independence,” she said. “Reading this makes the heroism of these men so personal.”

Digging through pages of centuries-old records isn’t just for herself, Linville is transcribing the cursive text to make it easier for others to access the documents as part of a joint volunteer project of the National Archives and Records Administration and the National Park Service.

Linville is one of about 4,700 volunteers who have transcribed roughly 100,000 documents. With 2.4 million pages in the pension files, the two government agencies are calling for more volunteers to help them uncover the stories of America’s first veterans who fought in the Revolutionary War.

The goal is to finish the work in time for the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence in 2026.

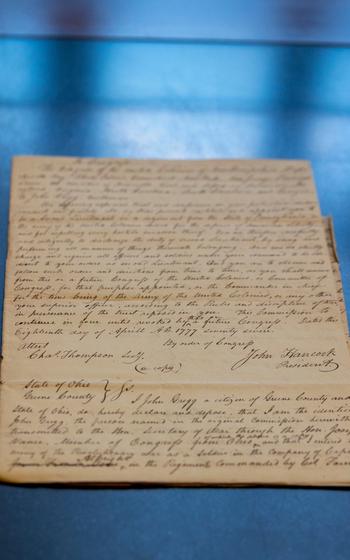

A handwritten copy of a resolution from Congress signed by John Hancock appointing John Gregg as an officer in the Continental Army dated April 18, 1777. (Eric Kayne/Stars and Stripes)

Hidden among the cramped, cursive writing are the personal narratives of service members trying to prove their service and earn a pension decades after the war’s end, said Suzanne Isaacs and Nancy Sullivan, the community managers who oversee the project for the National Archives, the government agency tasked with preserving government records.

“If anyone has the opportunity to really sit down and read some of these, you’re going to get sucked in,” Sullivan said. “Some of [the veterans] are really great with words and can really tell a good story.”

Without formal discharge papers, most veterans tried to prove their service by describing their experiences. Many are filled with anecdotes that paint a portrait of colonial military service.

Jacob Hickman’s file shows he would go home from the military every other week to tend his crops. Andrew Gillespie volunteered with a horse from his uncle and carried dispatches from his officer to the printing office. Philip Morris detailed a battle in Rhode Island, where troops were ordered to fire a log chain from a brass cannon when they ran out of cannonballs.

The more than 83,000 pension files were stored within the War Department, now the Defense Department, for decades before making it to the National Archives. In the 1970s, the pension files were scanned onto microfilm, which was later digitized.

But the original documents were handwritten and worn from being folded and mailed more than 200 years ago. Transcribing the text makes the documents easier to read and more accessible to the public.

“There’s a lot of valuable information for different audiences,” Sullivan said.

Historians and genealogists often use the records to learn more about who participated in which battles. People looking to join certain organizations, such as the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution can use the pension files to prove their ancestor’s service.

The veterans at the time also had to prove they were in financial need of a pension, so some documents include lists of their household goods and their value or the number of children they support.

The National Park Service recently began pitching the project to its pool of volunteers in hopes to include some of these personal stories in celebrations of the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence and early battles of the Revolutionary War.

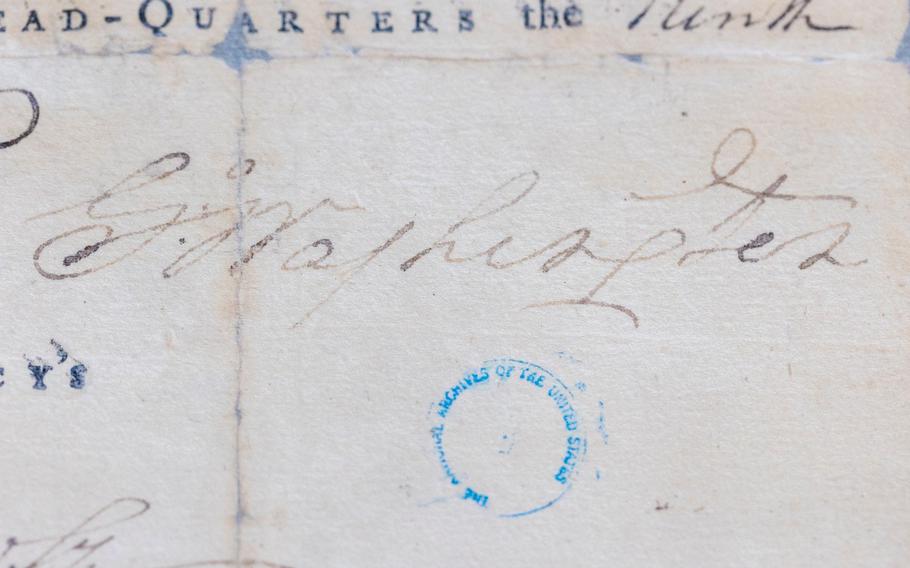

George Washington’s signature is shown on a military discharge certificate from the Continental Army for Gill Boidré dated June 9, 1783. (Eric Kayne/Stars and Stripes)

Many of those battlefields are now preserved in the national park system, such as Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, Minute Man National Historical Park, Boston National Historical Park and Fort Stanwix National Monument.

“This is really a great opportunity for us to tell a more complete and comprehensive American story as related to the American Revolution,” said Frank Barrows, senior adviser for national commemorations and community engagement for the National Park Service. “They provide windows into the lives of our first veterans and their families from a first-person perspective, and they help our interpreters in the field to connect the public with all of these stories.”

At Guilford Courthouse, the park uses the pension file of Thomas Mason, a “free man of color,” to provide a personal account of the battle as well as the long fight many Black veterans and their families faced to receive a pension. He was one of about 5,000 Black men who fought in the Revolutionary War.

His widow Elizabeth Mason filed for his pension in 1854 from Campbell County, Va. Then 90 years old, she included details she’d heard him share before his death 22 years earlier.

The pension was denied for several reasons, with one objection on the grounds that the man processing the claim did not believe freed Black people in Virginia could marry.

Some of the records also included references to famous veterans of the war, such as George Washington and John Hancock, as well as their signatures among the few discharge papers that were issued.

With all the records available online, volunteers can transcribe records from home. For those who can’t read cursive, tagging the documents to make them easier to search is just as important, Isaacs said.

“If you read enough of these, you’ll realize that there is inconsistency with spelling,” she said. “So, by people tagging the correct spelling and the way we would like it tagged, then we’re able to find all these records.”

People who volunteer through the National Park Service can receive a volunteer pass that grants free access to all parks once they contribute 250 hours.

“This partnership is about national parks being in the forever business,” Barrows said. “The impacts of this project will live far beyond the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence because these stories will become part of the permanent record. Researchers will have access to this treasure trove information in perpetuity.”

For Linville, who volunteers from her home in Tennessee, she said reading the documents makes her proud that her work helps others access these veterans’ stories.

“What these men experienced and the sacrifices they made are the foundations of patriotism and love of country generations later,” she said.

Learn how to volunteer for the project at https://www.archives.gov/citizen-archivist/missions/revolutionary-war-pension-files.