Blake Hibray located his late father’s souvenir Japanese military rifle after it had been missing for 78 years. He traced the weapon using its serial number, which he spotted on an old shipping form left in his father’s Navy-issued wooden footlocker, shown here. (Blake Hibray)

WASHINGTON — Arthur Hibray piloted PBY Catalina “Dumbos” — seaworthy planes equipped with boat hulls — across the Pacific theater during World War II performing air-sea rescues of downed aviators and sailors in distress.

After the war ended in 1945, Hibray flew over Hiroshima to view the devastation and into Osaka, where he purchased an Arisaka Japanese military rifle with a bayonet as a souvenir and had it shipped back to the United States.

But when he stowed the weapon at Iowa State University after returning home from military service, someone rifled his dormitory locker and took the weapon. He never saw the rifle again.

Hibray, a former Navy lieutenant who served from March 1943 to January 1946, died in 2020 at the age of 96. But his son, Blake, did not forget the souvenir military rifle or the mystery of its disappearance.

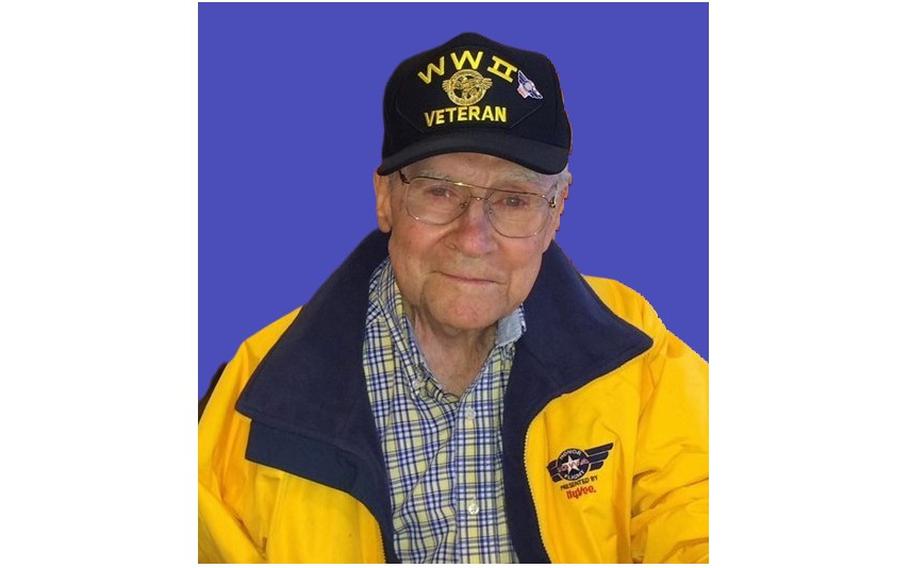

Art Hibray, a former Navy lieutenant, piloted PBY Catalina “Dumbo” planes making air-sea rescues in the Pacific theater in World War II. Hibray died in 2020 at the age of 96. (Hibray family photo)

Blake Hibray, 63, of North Carolina said he realized there might be an opportunity to track down the rifle as he was sorting through his late father’s belongings in the summer.

He was going through his father’s military gear in a Navy-issued footlocker that contained flight instruction manuals, flight logs, uniforms, naval orders and maps neatly packed as his father left them.

Hibray pulled out a tightly folded piece of paper the size of a Post-it note, smoothed it out and saw it was a transportation request form his father filed with the Navy for permission to send the rifle back to the U.S.

“I was very surprised,” he said. “The rifle was long gone at that point. And here was an original shipping document — the ‘certificate of retention of captured materials by Navy personnel.’ I did not know it existed.”

Along with a description of the rifle was the weapon’s serial number. Could the number help Hibray locate the rifle? He thought it was worth a try.

Art Hibray’s feats as a Navy pilot had fascinated his son growing up in Harland, Iowa.

Blake Hibray’s father was the son of farmers in South Dakota but he was called to active duty in March 1943 at the age of 18. He told his family that he wanted to fly military planes.

“When he joined the Navy, he had a choice on the type of planes he wanted to fly. He went with multiengine PBY Catalinas — the Dumbos — that handled air-sea rescues,” he said.

After attending pre-flight school in Iowa City, Art Hibray learned to fly biplanes at Naval Air Station Hutchinson in Kansas. He then moved on to Pensacola and Jacksonville, Fla., where he trained on the PBY Catalinas.

“On May 2, 1944, I graduated as a naval aviator and received my ‘Wings of Gold’ and was commissioned as an ensign in the U.S. [Navy] Reserve,” Art Hibray wrote in a memoir of his military service that he penned for his family. “I was 19 years old at the time — became 20 the following week. From Pensacola, I went directly to the naval air station in Jacksonville, Fla., for three months of intensive operational training in the PBY Catalina.”

After World War II ended in 1945, Hibray, a 21-year-old naval aviator, purchased a souvenir Japanese military rifle with bayonet at a store in Osaka, Japan, and shipped the weapon home. It was later stolen from his dormitory locker at college. He never saw the rifle again. (Hibray family photo)

He flew the Dumbo aircraft in the South Pacific for several months.

“Landing a PBY in the ocean was always a tricky maneuver,” Art Hibray wrote. “The water could be very choppy with big waves if it happened to be windy. If it was quiet, the swells of the ocean could be a problem.”

Years later, he recalled the air-sea rescue of a downed Marine pilot who had been flying an F4U Corsair.

The Marine pilot was making strafing runs after bombing a target in New Guinea when his plane was hit by an anti-aircraft shell. The plane went down and sank almost immediately.

“They were able to swoop in, pick up the pilot and return to base without incident,” Blake Hibray said.

Art Hibray wrote of piloting the Dumbos and described two futile patrol flights that he made to search for survivors of bombers that had gone down. He never forgot those events.

“We were able to find oil slicks and trash in the ocean, which might have some connection, but unable to find any survivors. I’ve thought many times that there might possibly be someone down there watching us fly over and leaving them stranded,” he wrote.

Art Hibray was next assigned to a squadron flying transport planes that ferried service members and supplies from January 1945 through the end of the war. Known as the R4D, the plane was the Navy’s version of the Douglas C-47 Skytrain.

“Dad had two very different roles as a Navy aviator. He got to fly Dumbo duty in the PBY Catalinas as part of Patrol Squadron VP-52 and VP-34,” Blake Hibray said.

But he also flew the R4D with the Flag Utility Unit, a special squadron of the Seventh Fleet.

“Basically, we flew officers and men of units that were moving closer to the action to make advance preparations,” Art Hibray wrote in his memoir. “We flew airplane engines and parts as well as other needed equipment that couldn’t wait for ships. I had the opportunity to fly several U.S.O. entertainment groups around to Navy and Marine bases.”

Hibray also piloted the R4D after the war ended to pick up American prisoners of war who had been held in Formosa, Japan. He transported them to Shanghai, China, where they were put on hospital ships and returned home to the United States.

“Dad was fortunate to stay out of harm’s way. Seeing and transporting the American POWs demonstrated to him how so many of our soldiers endured indescribable life events while serving in the Pacific theater,” Blake Hibray said.

Hibray kept his pilot’s license active when he left military service and returned home to Iowa in March 1946.

The rifle’s purchase and unexplained disappearance was one of many stories of military service that Hibray shared over the years with his wife, Donafae, and their four sons. Blake Hibray is the youngest.

“My dad maintained a passion for the Navy, and in particular, the Navy air corps throughout his life,” Blake Hibray said. “Our evenings were often filled with the stories that Dad recounted from his naval service. My older brothers and I grew up attending the annual flight demonstrations of the Blue Angels and the Thunderbirds. As adults, we continued going to these events with my dad, even when he was well into his 90s.”

Hibray said he knew the chances were slim for locating the rifle. After all, the rifle had been missing for nearly 80 years. But Hibray said he thought it was worth it to try to track the weapon using the serial number on the old shipping form.

Hibray did an online search for a Japanese World War II-era rifle with the serial number referenced in the document. The result was immediate.

“Eureka! I found a link to an auction house in Ohio that had sold a weapon in February with the exact same serial number,” he said.

Hibray emailed Apple Tree Auction Center in Newark, Ohio, and inquired whether this could be the same rifle as his dad’s. Sam Schnaidt, owner and auctioneer, called him the next day.

“He was quite positive the rifle was my father’s, as the likelihood of another rifle with the same serial number was remote at best,” Hibray said.

Schnaidt then contacted the new owner of the rifle, who promptly agreed to return it to Hibray, if he covered his cost to purchase the weapon. The exchange was made.

“Mr. Hibray told me the story about his father having it stolen from his locker when he was going to school under the GI bill. I contacted the owner who bought the firearm at auction. He said ‘I would be happy to sell it to him. If it were my father’s I would want it,’ ‘‘ Schnaidt said.

A week later, Hibray received his father’s long lost Arisaka Type 99 bolt-action carbine rifle.

But the auction house had scant information about the history of the firearm’s ownership. The rifle was part of a large consignment with several other Japanese military rifles sold at auction.

Though they look unusual, the World War II-era rifles with bayonet are common, Schnaidt said. Many troops brought them home as souvenirs, he said.

“I still have no idea how many times this rifle has exchanged hands over the years, or how it got from an Ames, Iowa, dormitory storage room to Ohio,” Blake Hibray said. “But that is not important.”

He ordered a wall-mounted case to display the rifle. He now has the rifle in his home office, along with some of his dad’s military photos and his footlocker from Navy service.

Blake Hibray keeps his father’s Arisaka Type 99 bolt-action carbine rifle in a display case in his home. “I have no idea how many times this rifle has exchanged hands over the years or how it got from an Ames, Iowa, dormitory storage room to an auction house in Ohio,” he said. (Blake Hibray)

Hibray recently invited a firearms collector to his home to have a look at the relic. The weapon is in nearly mint condition.

“In his opinion, it looks like the rifle was used but he cannot be certain. The stock was showing some wear,” he said. “Whoever owned the rifle took good care of it. I am now the caretaker of this special memento that has been repatriated to the Hibray family after some 78 years.”