Yet Huie’s own research notes, recently released by the descendants of a lawyer in the case, indicate his reporting showed that others were involved and suggest he chose to leave that out when it threatened the sale of his story. He also was seeking a movie deal about the killing and had agreed to pay the two acquitted men, J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant, part of the proceeds. (Associated Press)

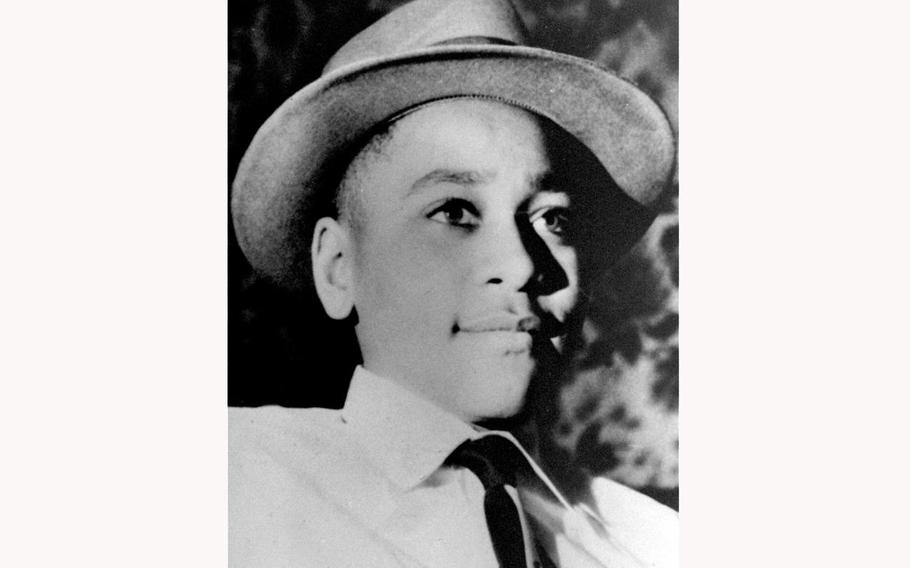

A journalist whose 1956 article was billed as the “true account” of Emmett Till’s killing withheld credible information about people involved in the crime, according to newly discovered documents.

William Bradford Huie’s article in Look magazine helped shape the country’s understanding of 14-year-old Till’s abduction, torture and slaying in Jim Crow-era Mississippi. The article detailed the confessions of two White men who previously had been acquitted by an all-White jury in the killing. The men told Huie they had no accomplices.

Yet Huie’s own research notes, recently released by the descendants of a lawyer in the case, indicate his reporting showed that others were involved and suggest he chose to leave that out when it threatened the sale of his story. He also was seeking a movie deal about the killing and had agreed to pay the two acquitted men, J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant, part of the proceeds.

If Huie had fully reported what he’d learned, it could have led to charges against additional participants in the murder, three historians say.

Protected by the U.S. Constitution’s double-jeopardy clause, Milam and Bryant told Huie after their acquittal that they had killed Till after Carolyn Bryant, Roy’s wife, claimed the boy accosted her in August 1955.

“Between 1955 and 2005, it was without question the single most influential version of the story. And [Huie] was intentionally protecting guilty people,” said Dave Tell, a University of Kansas professor whose 2019 book, “Remembering Emmett Till,” was harshly critical of Huie’s reporting.

Till’s brutal killing shocked the world and helped galvanize the civil rights movement. But misconceptions of the events leading to his death have persisted, and the FBI has reopened the case several times - most recently in 2017.

In addition to Huie’s 33-page research notes, the newly released documents include letters he exchanged with John Whitten, one of the men’s defense attorneys. Whitten’s granddaughter, Ellen Whitten, found the documents in April and with her mother donated them to the Emmett Till Archives at Florida State University [diginole.lib.fsu.edu].

“I think shedding light on historical wrongs is never a bad thing,” Ellen Whitten said in an interview. Deborah Watts, Till’s cousin and co-founder of the Emmett Till Legacy Foundation, said the revelations in the documents are important.

“But in terms of vindication? Emmett died. And he died because of a number of lies,” she said. “We knew that they were lying on Emmett. We knew there were many that sought a profit and a payoff from the pain that our family experienced.”

Davis W. Houck, the founder of the Till archives and co-author of a book about media coverage of Till’s murder, shared the documents with The Washington Post and Mississippi Today ahead of their public availability. Mississippi Today published its story earlier this month.

Huie died in 1986. His stepdaughter Mary Ben Heflin, who manages his estate, said that although she hasn’t seen the documents, she was aware of previous criticism and had “no doubt that Huie wrote as much as he legally could at the time about the facts in this case.”

‘The true account’

Huie was born and raised in Alabama. By the mid-1950s he was a best-selling author, popular speaker and co-host of a TV talk show, and was hired by the New York Herald Tribune to cover civil rights in the South.

When Huie’s article hit national newsstands, the impact was immediate. White Mississippians, who had previously supported Milam and Bryant, turned against them. U.S. Rep. Charles Diggs (D-Mich.), one of the few Black members of Congress at the time, read the article into the congressional record. One Black newspaper hailed Huie’s “spectacular” reporting.

The story had an additional effect: Black journalists had been pressuring Mississippi officials and the FBI to investigate and charge additional suspects in the case. Huie’s “true account,” with its assurance that only two men were involved and its depiction of Till as a defiant brute, effectively ended that effort.

“This confession, as it was touted, suddenly seemed enough to satisfy everybody,” said Devery S. Anderson, author of a 2015 book on the Till case. If Huie had reported everything he had learned, “it’s possible these other people would have been indicted,” Anderson said, though he also said they might have been acquitted.

Experts now agree on this basic timeline: On Aug. 24, 1955, Till whistled at Carolyn Bryant outside the convenience store where she worked. What, if anything, happened inside the store is unknown. In the early hours of Aug. 28, Milam and Bryant, along with at least two and perhaps five accomplices, went to the home of Till’s great-uncle and great-aunt Moses and Elizabeth Wright, and abducted Till at gunpoint.

They put him in the back of Milam’s truck, and one or more Black men who worked for Milam held Till down. They drove to the farm of Leslie Milam, another brother. A group of White men beat and tortured Till inside the barn, and Black neighbors heard Till crying and begging for his mother. Milam shot Till in the head, and Till was either dead or dying when he was loaded back into the truck around sunrise. His body was tied to a 74-pound gin fan with barbed wire and dumped into the Tallahatchie River. It was recovered on Aug. 31.

Huie’s article said that Till accosted Carolyn Bryant inside the store and asked her for a date before going outside and whistling at her. Days later, Huie wrote, Milam and Bryant abducted him. They had never met Till but knew it was him because the boy identified himself.

Till lay in the back of the truck for three hours while the men drove around looking for a cliff where they’d planned to scare him, Huie wrote. Unable to find it, they took him to Milam’s tool shed and pistol-whipped him. Till, who hardly bled, boasted of having sex with White women, Huie wrote. The men then decided to kill him, the article said. Till loaded the gin fan onto the truck by himself. At the riverbank, Milam shot him in the head.

Huie’s research notes say he first arrived in Sumner, Miss., on Oct. 6, 1955, two weeks after Milam and Bryant’s acquittal. He met with the men’s defense attorneys, J.J. Breland and John Whitten, and proposed an idea: If they could help him obtain “the complete and truthful cooperation of every White man who had been involved in the abduction-and-slaying,” then he might be able to make them all rich. He wanted to write an article, then a book, a stage play and a movie, and he would share a percentage of the proceeds of each project with the men and their attorneys.

They negotiated the terms for a few weeks. “At this point both Mr. Whitten and I were under the assumption there had been four White men in the abduction-and-slaying party,” Huie wrote in his research notes. Huie agreed to pay $3,150 and pitched the story to Look magazine, which insisted that every person named in the story sign a release form to protect the magazine from libel claims.

Both Whitten and Huie were surprised when, on Oct. 23, only Milam and Bryant showed up to be interviewed, claiming no one else had been involved in Till’s murder.

A third kidnapper?

Huie met with Milam and Bryant several times, and in his research notes he repeatedly expressed doubts about the story they told him. He expressed even more doubts in letters to Whitten after he’d traveled to Chicago to interview Black witnesses.

In a Dec. 10, 1955, letter, Huie told Whitten he interviewed Elizabeth Wright, whom he found “intelligent,” and who, he wrote, “talked mighty convincingly about the ‘third man’ who came in her room and spoke with her” during the kidnapping.

“She said it was Milam’s brother-in-law from Minter City,” Huie said in the letter.

Milam had a brother-in-law in Minter City named Melvin Campbell. In a heavily redacted 2006 report by the FBI, investigators said Melvin Campbell told an unnamed person he was with Milam and Bryant the night Till was murdered. Campbell did in 1972.

Huie never mentioned Wright’s claim of a third kidnapper in the Look article. If he had, Look would have required Campbell to sign a release form.

Anderson said this new information changes what he thinks about Carolyn Bryant, whom he had long suspected of being inside the truck the night Milam and her husband kidnapped Till. If Campbell participated in the kidnapping, then “there isn’t really room for her in the truck,” Anderson said.

Anderson said he now thinks it’s more likely that another person identified Till.

If Huie had reported everything he was told, Houck said, “There’s going to be some people in the White press who continue to say, ‘Okay, then why aren’t we prosecuting? Why isn’t the DA in Tallahatchie County prosecuting them?’ He essentially shuts down the case legally.”

Doubts creep in

In his research notes, Huie also wrote “there appears no doubt” that Carolyn Bryant’s claim that Till accosted her was “fabricated - probably at the suggestion of one of the lawyers.” But in the Look article, he published her claim as fact. Bryant died last year.

Huie also repeatedly expressed doubts about Milam and Bryant’s claim that Till sat in the back of the truck unrestrained.” He wrote of challenging them on how unbelievable it was that Till didn’t try to escape.

Huie concluded: “It still sounds unreasonable to me, but all that can be said in its defense is that it makes more sense than any other explanation.” In the article, he reported the “impudent” Till sitting in the truck for hours as fact.

“That part makes me mad,” Tell said. “They invent the myth of a defiant, stoic Emmett Till because they need to get rid of [the Black men], who are in the back, guarding him.”

In the Dec. 10, 1955 letter to Whitten, Huie asked about one of those Black men, Levi “Too Tight” Collins, long believed to have been forced by Milam to participate in the kidnapping. Huie also mentioned Willie Reed, an 18-year-old Black passerby who had testified he caught a glimpse of Till in the back of the truck and heard him being tortured in Leslie Milam’s barn. Both Collins and Reed fled to Chicago after the trial, where their stories circulated.

“I listened to so much of this stuff in Chicago that I began doubting myself,” Huie told Whitten, “and one night I was on the point of coming back to Mississippi and ‘pistol-whipping’ Milam for telling me a fabric of lies.” He then asked Whitten what he knew of Collins’s claims about Milam, admitting it was “too late for me to ask you to reassure me on this point.”

Huie doesn’t mention Reed or Collins in his story. Doing so would have required him to get a signed waiver from Leslie Milam, the third brother in whose barn Till was beaten. Instead, he published as fact a claim he doubted - that Till was beaten somewhere else. In 1974, Leslie Milam summoned a minister to his home and confessed he had been “personally involved” in Till’s murder, according to the FBI. He died the next day.

- - -

The ‘propaganda business’

In a Dec. 20 letter to Whitten, Huie hinted that he pitched the story to Look because of its lax editing practices, writing: “I dealt with a magazine with which I could exercise this control.

“You see, John,” he boasted, “I’m very old in this propaganda business. I know how to fight smart … so smart that my ‘enemies’ don’t realize just what is being done to them at times.”

He explained that although some readers might think his article was a “godsend to NAACP,” it was no such thing.

“Most Negroes want to be white,” he wrote, and “virtually all American Whites are opposed” to “interracial marriage,” so Huie had included an anecdote about Till having a picture of a White girl in his wallet. It would “pinpoint the hypocrisy” of White “liberals” and leave them “very uncomfortable.”

The comments in the letter are at odds with Huie’s reputation as being sympathetic to the civil rights movement. The Black writer Zora Neale Hurston considered him a friend, and Martin Luther King Jr. wrote the foreword to Huie’s book about the 1964 murders of three civil rights activists.

In other letters, he bragged about selling a negative story about Till’s father - whom Till never met - to a “slander sheet,” which he hoped would please White Mississippians. He coached Whitten on how he and the killers should lie about having met or spoken to Huie.

Mostly, he wrote of his efforts to get the movie made, promising to maintain control of the project so Till wouldn’t be depicted too sympathetically. The movie never got made, although Huie eventually published a book about Till’s murder and other stories.

‘M + B, destroy’

At some point, John Whitten removed the folder containing the notes and letters from his office. On the folder he wrote: “M + B, destroy.”

But shortly before his death in 2003, he told his daughter-in-law - Ellen Whitten’s mother - where in his house he’d hidden the documents, in case anything happened to him.

Ellen Whitten was 19 when he died. She never asked him about the case, because she’d never heard of Emmett Till. “It’s not something they teach in schools in Mississippi,” she said. “Well, they do now. They did not at the time.”

After she donated the documents to the Till archives, Houck called with news of their significance. He warned that her grandfather “does not come off well in these letters.”

She doesn’t know what to think. In the end it doesn’t matter, she says. She just wants the information public.

“I would hope that if anyone else had documents related to the case they’re feeling sort of uncertain about, I think bringing it all to light helps,” she said.