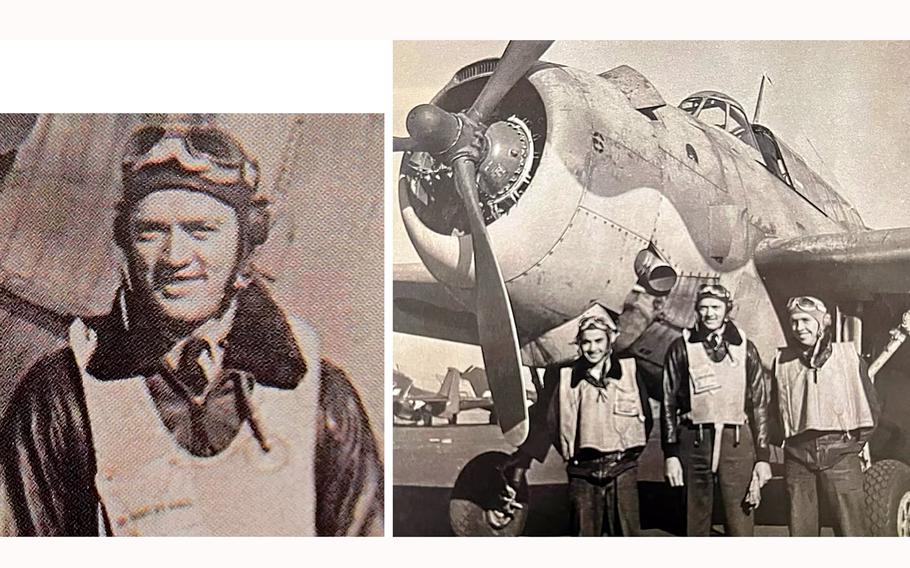

On Sept. 10, 1944, U.S. Navy Reserve Lt. Jay R. Manown Jr., took off from the USS Enterprise aboard a TBM-1C Avenger, to conduct air strikes against enemy targets in the South Pacific. The plane was struck by enemy fire and crashed. There were no indications that Manown or the other two crewmembers exited the stricken aircraft prior to the crash, and all efforts to recover their remains were initially unsuccessful. (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency)

MORGANTOWN, W. Va. (Tribune News Service) — Together, they were their own war movie.

Anthony Di Petta.

Wilbur Archie Mitts.

Jay Manown Jr.

For generations, this trio of aviators was feared forever lost to World War II and the ages when their Avenger aircraft was shot down Sept. 10, 1944, near the island of Palau in the South Pacific.

Thanks to high-tech forensic analysis and recovery efforts, however, two of the heroes are now home—and a third is about to be.

First, though, some history.

Di Petta, the gunner, was born in Italy and grew up in New Jersey.

He was a proud son of immigrants who mustered in to the military without hesitation when it came time to defend the homeland that was still new to his parents—and by then second nature to him.

Mitts, the radioman and navigator, had All-American written all over him.

With the nation still reeling from the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, Mitts drove up the California coast from his home in Seaside to San Francisco, so he could enlist.

At 26, Manown, the pilot and north-central West Virginian, was a couple of years older than his crewmates.

He was a WVU graduate and Morgantown native who also had family in Kingwood.

The lieutenant was working as a flight instructor with the U.S. Navy Reserves—but he quickly returned to active duty after Pearl Harbor.

Manown had already flown several combat missions as he and Di Petta and Mitts did the final flight check on the deck of the U.S.S. Enterprise aircraft carrier that September morning nearly 80 years ago.

Something in the air The island-hopping campaign in the South Pacific was particularly grueling and bloody.

Stealth ambushes and close-quarter fighting abounded on the exposed beaches and dense jungles of those islands.

Overhead, the skies weren’t just blackened with the ack-ack of anti-aircraft fire.

They were also noisy, in a most deadly way.

It was a lethal cacophony, punctuated by the deep-dive whines of the Japanese Zeros swooping in to engage the Americans in the air while also attacking invading destroyers lobbing their ordnance inland.

Palau promised more of the same.

The orders were to take out anti-aircraft positions and transport ships near the island nation almost equidistant to The Philippines and the coast of Japan.

If you believe in that sort of thing, you could say grim, wartime averages finally caught up with the plane carrying the Mountain State native, the Californian and immigrant kid from New Jersey during the run.

By eyewitness accounts, Manown’s plane was slammed.

It was last seen violently spinning into the waters of Malakai Harbor. No parachutes were spied.

The “We regret to inform you that your son is reported missing in action, “ telegrams from Western Union went out to three families—and the Gold Stars went up in the windows of three boyhood houses that would never be the same.

Or maybe those Gold Stars didn’t go up.

No bodies were fished out of the sea on Sept. 10, 1944, and five years later, the government declared the plane and its crew non-recoverable.

A pilot, navigator and gunner, gone.

Investigators speculated later that Manown took the full impact of an incoming round and was most likely killed instantly—which is what this story is really about.

That’s because Project Recover had its own mission.

Bringing them home Project Recover is a civilian-based, nonprofit organization traveling the world searching for the soldiers who never got to come home from war.

In its 30-year existence, it has accounted for more than 80 military personnel missing in action for decades from the former war zones of the world.

The remains of 17 soldiers have been recovered and repatriated in recent years. Di Petta and Mitts are in that group—and Manown, as said, is soon going to be.

A Project Recover team made a positive identification of the pilot in May through mitochondrial DNA analysis as well as an “anthropological and circumstantial “ accounting of the scene, the team said, that also included the recovery of parts from the Manown’s plane.

The team talked about it for a feature in the March edition of Smithsonian magazine.

Spent shells from the 50-caliber gun Di Petta fired from the turret during the tumult of the airborne battle were discovered in the bay’s waters that day, the team told the publication.

So was a sheared sheet of metal from the cockpit there to protect the pilot, leading the team to speculate whether the front of the Avenger sustained a direct hit, which Manown, as the team said, wouldn’t have survived.

Now, the remains of the pilot are coming back to the Mountain State, where they will be interred with full honors in a service Oct. 29 at Maplewood Cemetery in Kingwood.

Details will be released closer to that date, said Gene Hughes, a public affairs officer with the U.S. Navy’s POW /MIA Division in Tennessee.

“That’s for the family, “ Hughes said Friday from his office in Memphis.

“Right now, we just want to focus on the fact that Lt. Manown is coming home.”

For the fallen ...

Meanwhile, “home “ and “family “ were the watchwords of this particular mission, the Project Recover team said after the announcement last week.

That’s because the pilot is now joining his gunner and navigator on American soil—after all these years.

A mini-Band of Brothers, they were and are.

Once lost, now found. An act of amazing grace—through science and mainly tenacity.

A crew, forever young.

Manown, as said, was the eldest on the plane, at 26 years of age.

The poignancy of lives ended that were just getting started wasn’t lost on the Project Recover team when the crash site was first identified in 2015.

Team members read the poem, “For the Fallen, “ in honor of the crew.

It was written by the British poet Laurence Binyon, who, at the age of 46, went to work as an orderly at a military hospital in France in World War I.

“ ... They went with songs to the battle, they were young, Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted ;

They fell with their faces to the foe.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning We will remember them ...”

(c)2024 The Dominion Post (Morgantown, W.Va.)

Visit The Dominion Post

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.