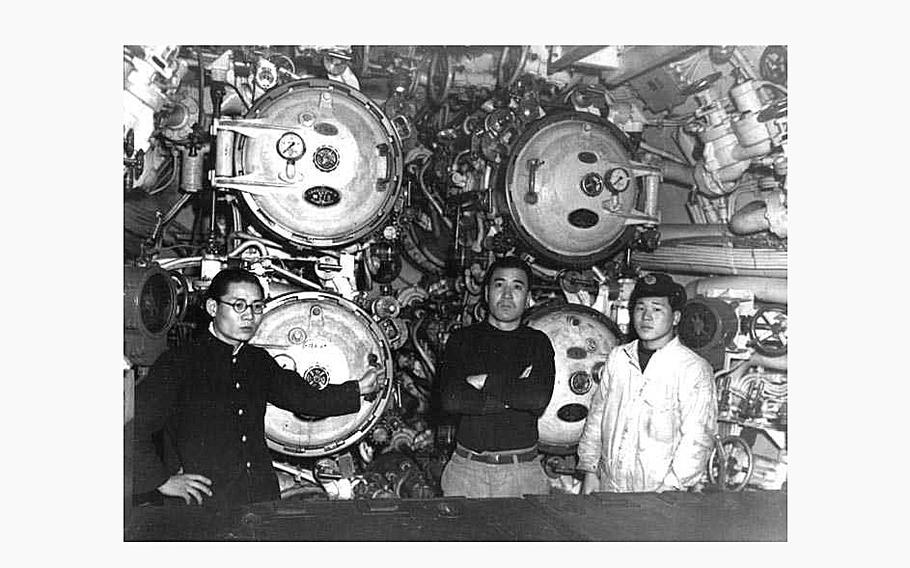

The forward torpedo room of an I.58 submarine is seen on Jan. 28, 1946 while awaiting scuttling at Sasebo, Japan. This submarine torpedoed and sank USS Indianapolis (CA-35) on July 30, 1945. (U.S. Marine Corps )

MASAKI, Ehime - For almost 20 years, former submariner Kunshiro Kiyozumi had made an annual trip each spring to commemorate his comrades who died near the end of the Pacific War, in suicide attacks using Kaiten “human torpedoes.”

The young soldiers boarded the suicide vessels ready to die, with no one to bid them farewell. Kiyozumi, now 96, residing in Masaki, Ehime Prefecture, had planned to quietly mourn the war dead at his home on this year’s 79th anniversary of the end of World War II.

In January 1945, Kiyozumi graduated from a diving school of the former Japanese navy and became a crew member of the I-58 submarine. At just 16 years old, he was the youngest of about 100 men. His various duties included taking care of the officers’ personal needs.

The I-58 was ordered to sail to waters off the Philippines in July that year. It departed from a port in Kure, Hiroshima Prefecture, and stopped at a base in Hirao, Yamaguchi Prefecture, with six Kaiten and six men to operate them.

Japan had already lost control of the sea. On the Pacific side of the Bungo Channel, Japanese warships were ambushed by U.S. submarines.

The Kaiten was a one-man suicide attack weapon measuring 14.75 meters in length and one meter in diameter. Developed based on a torpedo, its name referred to the hope that it would “turn the heavens around and reverse the tide of the war.”

These human torpedoes were carried on the deck of a submarine and launched when a target, such as an enemy tanker, was located. The crew member inside maneuvered the torpedo to hit the target.

A total of 106 Kaiten crew died in the war or in accidents during training.

Before leaving Japan, the submarine surfaced at night. Kiyozumi witnessed a superior officer showing the Kaiten crew the land of Kyushu. He brought them sake at the superior’s instruction, after which the officer and the crew poured each other drinks, saying: “This will be our farewell cup.”

Five of the Kaiten crew on the I-58 departed on missions before the war ended. He later heard that when they were ordered to go out, almost all of them said, “Thank you for everything.” When the time came for the launch, each crew member climbed the ladder and closed the hatch, with no one to see him off.

“I wonder how they felt as they climbed aboard and closed the hatch with their own hands. I still feel sorry for them,” Kiyozumi said.

At the end of July, the I-58 sank the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis. It was later learned that the vessel was on its way back from carrying parts of an atomic bomb.

However, “none of us could rejoice from the bottom of our hearts,” Kiyozumi said, as two Kaiten crew members had lost their lives just the day before.

He heard about the end of the war while on the submarine. The I-58 returned to the port in Kure in late August, with Kiyozumi on board.

One day, when Kiyozumi was working at a power distribution equipment company, he received a phone call from a fellow crewmember on the I-58. They were close in age and were good friends, but they had not seen each other since they parted at the Kure port.

The crewmember said he made a memorial visit during cherry blossom season each year to Otsu Island in the city of Shunan, Yamaguchi Prefecture, where a Kaiten training base was located. Kiyozumi decided to join his friend, saying to himself, “I’m alive thanks to those who went out in the Kaiten.”

Nearly 20 years have passed since then. This spring, Kiyozumi visited the island again to pray for the Kaiten crew members. The friend passed away several years ago.

Kiyozumi is probably the only surviving I-58 crew member now. He still regrets the loss of young lives. “As long as I’m alive, I’ll make trips to console the spirits of the dead,” he said.