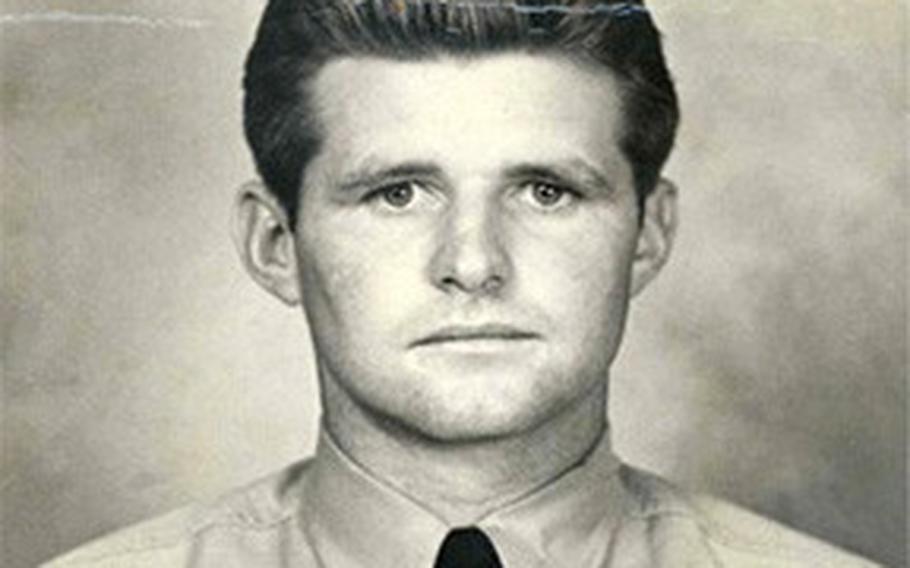

Aviation Cadet Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., older brother of President John F. Kennedy, pictured during flight training in 1942. He was killed in action when the PB4Y-1 Liberator he was flying exploded during a combat mission over Europe in August 1944. (National Naval Aviation Museum)

On Aug. 12, 1944, airplane mechanics, pilots and cooks gathered near the runway of an air base in England to watch the takeoff of a top-secret Navy aircraft that was painted white and had a huge “T-11” emblazoned on its side.

The plane was jammed with tons of a potent explosive called Torpex, which was used in torpedoes. And it had special electronic equipment that, once airborne, would transform it into a crude but powerful drone.

At the controls was Navy Lt. Joseph P. Kennedy Jr., 29, the oldest son of a former U.S. ambassador to Britain, and a man who carried the promise of one of the great political families in American history.

But on this day, 80 years ago Monday, he was also about to become the first to perish in a string of public tragedies that would afflict his family for the next half-century.

“The best ones seem to go first,” his younger brother, John — himself destined for assassination — would say a few months later.

Shortly before 6 p.m., according to author Hank Searls’s biography of Joseph Kennedy Jr., the converted B-24 bomber took off, bound for a suspected Nazi missile site in France.

Once aloft, Kennedy and co-pilot Lt. Wilford J. Willy, 35, were to turn over electronic control of their aircraft to another plane and parachute out. The pilotless bomber would then be remotely guided to crash into its target.

About 18 minutes into the flight, Kennedy radioed “spade flush,” the signal for the other plane to take control. A few minutes later, over the English village of Blythburgh, T-11 blew up with two shattering explosions.

Wreckage, including several of the airplane’s engines, fell across the local countryside. A bomb bay door was found. Some buildings were damaged. But no remains of Kennedy or Willy were ever recovered. The exact cause of the blasts was never determined.

The disaster devastated their relatives and altered the path of the Kennedys, the famous Irish American family that would leave its mark on the country as no other.

The next day, a Sunday, Kennedy’s parents, the millionaire businessman Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., 55, and his wife Rose, 54, were gathered with some of their nine children in their Hyannis Port, Mass., home.

They had just had lunch on the porch.

John, 27, known as Jack — a hero Naval officer and future U.S. president — was there. So was Robert, 18, who was in a Navy officer training program and would become a U.S. senator, and Edward, 12, also a future U.S. senator.

Years later, Robert F. Kennedy would die at the hands of an assassin. John’s son, John Jr., and the older Kennedys’ sister, Kathleen, would die in plane crashes. Edward’s life would be marked by a car accident that killed a young woman he was with. And in 1941 the siblings’ troubled older sister, Rosemary, had quietly undergone a disastrous lobotomy that left her institutionalized.

There were more sad times for the family in the future, but on this summer day Joseph Kennedy Sr. had gone upstairs to take a nap, Rose Kennedy wrote in a memoir.

She was reading the Sunday paper. Some of the children were talking quietly in the living room so as not to wake their father.

Others were on the porch.

There was a knock at the door. Two Catholic priests said they needed to talk to her and her husband. It was urgent. “Our son was missing in action and presumed lost,” she wrote. She hurried upstairs and got her husband. The priests gave them the news.

“We realized there could be no hope and that our son was dead,” Rose wrote. Joseph Sr. told their children, who were stunned, especially John. “For a long time he walked on the beach in front of our house,” she remembered.

The two brothers had long been engaged in fraternal rivalry — mostly on the part of Joseph Jr.

“Within the family, Joe Junior, as the eldest son, was accorded an initial position of primacy,” historian Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote in her book “The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys.”

He was mentor, role model, and responsible big brother — “the Kennedy golden child, marked for greatness by parents and grandparents,” historian Fredrik Logevall wrote in an email last week.

When he was born his grandfather, veteran Boston politician John Francis Fitzgerald, told reporters the boy would one day be president. And as an adult Joseph Jr. told people he would be the first Catholic president, according to Searls, his biographer.

“The drive to be supreme among the nine Kennedy children had always been an all-out obsession for Joe more than for Jack,” historian Logevall wrote in his book, “JFK: Coming of Age in the American Century, 1917-1956.”

But with the advent of World War II, the landscape changed.

Both men joined the Navy. Joseph Jr. went into aviation and, at first, had the relatively unglamorous job of flying large Navy patrol planes out of Puerto Rico and Norfolk.

Jack was sent to the Pacific where he became skipper of a fast patrol torpedo boat, PT-109, in a combat zone.

On the morning of Aug. 2, 1943, PT-109 was struck and cut in two by a speeding Japanese destroyer northwest of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. Two men were killed and others were badly burned.

But Jack, an expert swimmer, managed to guide his surviving men through the water to a nearby island, dragging one man in a life jacket by holding its strap with his teeth. They were rescued several days later and the story made front-page headlines.

“Kennedy’s Son is Hero in Rescue of P-T Men,” an Atlanta newspaper said. “Kennedy’s Son Hero of PT-Boat Saga,” said the Boston Evening Globe. The San Francisco Examiner, in a glowing story about John’s exploits, mistakenly ran a photo of Joseph Jr.

“This was the first time Jack had won such an ‘advantage’ by such a clear margin,” Rose Kennedy recalled in her memoir. “And I daresay it ... must have rankled Joe Jr.”

In September 1943, Joseph Jr. was home on leave in Hyannis Port and was at a dinner for his father’s 55th birthday.

One of those present was Judge John J. Burns, an old friend of his father’s, according to Logevall.

Burns proposed a toast: “To Ambassador Joe Kennedy, father of our hero, our own hero, Lieutenant John F. Kennedy of the United States Navy.”

There was no mention of Joseph Jr., who was about to ship out overseas to England and the European war.

That night, Joe Jr. shared his bedroom with another guest, Boston Police Commissioner Joseph Timilty. After they turned in, Timilty said later, he heard Joseph Jr. crying and saying to himself, “By God, I’ll show them.”

Once overseas, Joe Jr. began flying long, cold patrols over the English Channel, the North Sea, and the west coast of France hunting for Nazi submarines and dueling with the occasional German fighter.

The weather often was terrible and there were frequent crashes. One returning patrol plane got lost in fog, missed England and slammed into a rocky island off the coast of Ireland.

Finding the German U-boats was hard. In March, 1944, Joseph Jr.’s plane spotted an oil slick on the water. He circled and dropped a homing torpedo, but there was no evidence of a hit and he headed back to base.

His tour was coming to an end. The allies were planning to land in Normandy on D-Day in June. And he felt he had accomplished little, wrote Searls, his biographer.

“He had not sunk a sub and his crew had not shot down a plane,” he wrote. “Jack had a combat decoration. He had none and time was running out.”

Frustrated, Joseph Jr. signed up for another tour.

D-Day, June 6, 1944, found his patrol plane stalking German surface ships and submarines, but without major combat. As the days passed, he became more aggressive and flew closer to enemy installations, drawing fire.

Then he was promoted and offered a desk job in London. He turned it down and decided to go home. He had packed up some of his gear and was to ready to leave when an opportunity that was tantalizing, dangerous and top secret came up.

Since mid-June the Nazis had been launching hundreds of primitive missiles called “buzz bombs” at London. They flew at 350 mph, were hazardous to intercept and were deadly, according to Searls. Their launch sites had been attacked but without much success.

The allies need a more precise weapon. They came up with the idea of packing a plane like the ones Joseph Jr. flew with explosives and flying it remotely into an enemy launch site.

Here was his chance. He volunteered for the mission.

Four days after he was killed, The Washington Post praised him in an editorial: “One of the greatest evils of war is the loss of those young men who might normally been expected to become the leaders of their generation.”

Sixteen years later, the generation’s torch of leadership was passed to another Kennedy tempered by war - his rival and younger brother, John.