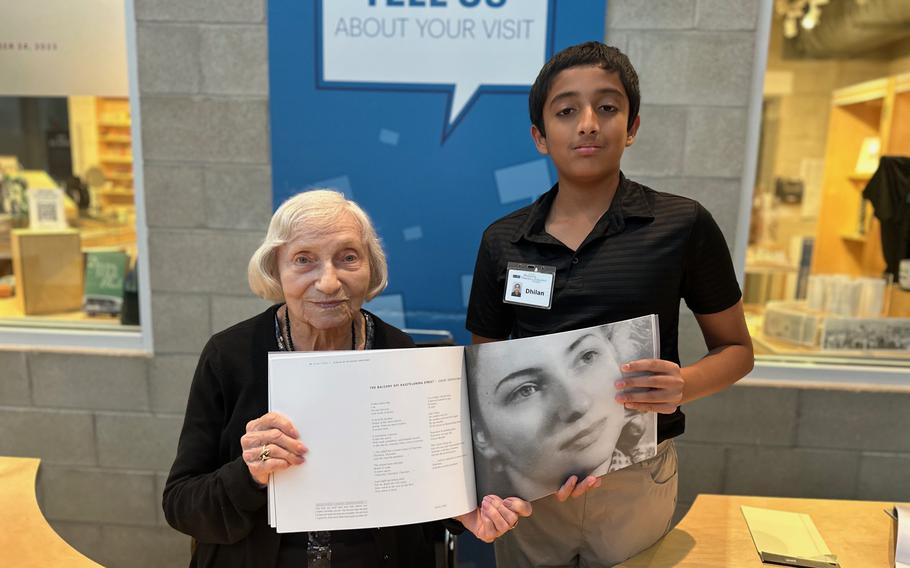

Janine Oberrotman and Dhilan Stanley with a copy of “In Our Voices: Stories of Holocaust Survivors.” Oberrotman is featured in the book. (Courtney Sturgeon)

Dhilan Stanley and Janine Oberrotman have been close friends since they met at the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center in Skokie, Ill., a year and a half ago.

They meet every Sunday to talk about books and history, and occasionally Dhilan will share his latest math and science grades. He is 13, and Oberrotman, a Holocaust survivor, is 98.

“I always look forward to seeing Janine — she’s shown me how important it is to live life to the fullest,” said Dhilan, who lives in the greater Chicago area and will be in the ninth grade this fall.

“Even with all she went through, she has no hate and is loving to everyone,” he said. “I know now that I can be more resilient in my own life because Janine was resilient as she survived one of the worst moments in history.” Dhilan and Oberrotman volunteer together at the museum’s welcome desk for several hours every Sunday.

Oberrotman has shared her story with visitors since the museum opened in 2009, while Dhilan started volunteering in late 2022.

Dhilan said he initially was assigned to clean headsets for guests who take self-guided tours, then he was transferred to the welcome desk after he met Oberrotman. “We just really hit it off,” he said. “When I was given the opportunity to work with Janine and help to share her story, I immediately accepted. I really admire her.”

He said his friend’s painful past has affected him deeply.

“It was hard to hear about what happened to her as a teenager during the Holocaust,” Dhilan said. “But I know it was important for me to hear it and to continue to see that others learn about her story.”

Janine Oberrotman, then Janine Binder, as a child in Poland before World War II. (Courtesy of Janine Oberrotman)

Oberrotman, then known as Janine Binder, was 15 when the German army occupied her hometown of Lvov, Poland. She and her parents were forced to give up their home and move into a ghetto with other Jewish residents.

When her father was caught stealing potatoes to feed their family, he was sent to the Janowska concentration camp adjoining the ghetto, where he was killed, said Oberrotman, an only child.

She said she escaped the ghetto using false papers provided by a friend, stating she was Catholic, then she moved in with her grandmother and uncle who were hiding in Poland. After her mother was killed during the liquidation of the Lvov ghetto in 1943, Oberrotman was arrested on the suspicion that she was Jewish, she said. Because the Gestapo had no proof of her family history, she was sent to Stuttgart, Germany, to work in forced labor, cleaning and washing dishes at a restaurant, Oberrotman said.

“It was a terrible time — you didn’t know what the right thing was to do; they were always trying to diminish you. You had to defend your own self-image,” she said. “I was lucky to work in a restaurant, but I never had a day off. I had to work constantly.”

At night, she slept in a cold room so small that it could barely hold a bed, Oberrotman said.

“I would cry for my mother, wondering what had happened to her,” she said. “After the war ended, I went home to find my family, but no family remained.”

Oberrotman moved to Paris, where she met and married Joseph Oberrotman, a Warsaw Ghetto survivor. In 1953, they immigrated to the United States and settled in Chicago to raise three sons.

One of them, Alain Oberrotman, said his mother, a former vocational counselor, immediately began sharing her story with anyone who would listen.

“She’s been doing this for decades — long before the museum was created,” he said. “In the beginning, she and other survivors had a foundation with programs about the Holocaust. My mother gave lectures every week about resilience and hope.”

Tens of thousands have heard her speak, Alain Oberrotman said.

Dhilan said when he met Janine in early 2023, he was drawn in by her positivity and the direct way she tells her story.

“She’s taught me about places I’d never heard of or seen on a map,” he said. “She’s taught me a lot about the events of World War II.”

Oberrotman said she was impressed by Dhilan, especially by his compassion and his desire to learn.

“He was very interested in my story, and he had a lot of questions that I was happy to answer,” Oberrotman said. “Right away, I enjoyed talking to him because he was so open. He’s a wonderful young man.”

Dhilan’s mom, Aarthi Vijaykumar, said she’s noticed a difference in her son since he started spending time with Oberrotman.

“He was never shy with his peers, but Dhilan was shy speaking with adults,” Vijaykumar said. “Within weeks of working with Janine, we saw a transformation.”

“As a parent, to see your child become more confident is a really nice thing to watch,” she said. “It also makes me happy that Dhilan wants to do this service for Janine and for the world. They are definitely a dynamic duo.”

People who walk through the museum’s exhibits on Sundays are often stunned to find a living survivor of the Holocaust waiting to tell her story with help from a teenager, museum volunteer Courtney Sturgeon said. CBS 2 News of Chicago recently shared their story.

“I used to sit with Janine at the museum when she’d come every Sunday without fail,” Sturgeon said. “Then about a year and a half ago, she became friends with Dhilan and very politely said, ‘You know, I think Dhilan and I have this.’”

Sturgeon said she didn’t mind.

“They have such a nice bond — it’s been fun to watch that grow,” she said.

Dhilan said he wasn’t aware that the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center existed until a traveling exhibit about genocide came to his school two years ago.

“It opened my eyes to the horrible atrocities that have been committed,” he said. “I took away that if people don’t pass the stories down and learn about what happened, we’re doomed to repeat it.”

With Oberrotman’s encouragement, he hopes to improve awareness through the Generation Z Against Genocide project he is working on through the Davidson Institute’s Young Ambassadors program.

“Meeting Janine has changed my life — probably forever,” Dhilan said, noting that he and Oberrotman each gave speeches for 1,700 guests at the museum’s annual humanitarian awards banquet in February.

“My message to other people my age is to go out and meet someone with a completely different perspective than your own,” Dhilan said. “You will definitely come away with more compassion and empathy.” His new close friend concurs.

“I tell Dhilan, ‘To thine own self be true,’” Oberrotman said. “Be who you are and try to stay that way. I know that he’ll do that. He’s a very smart person.”