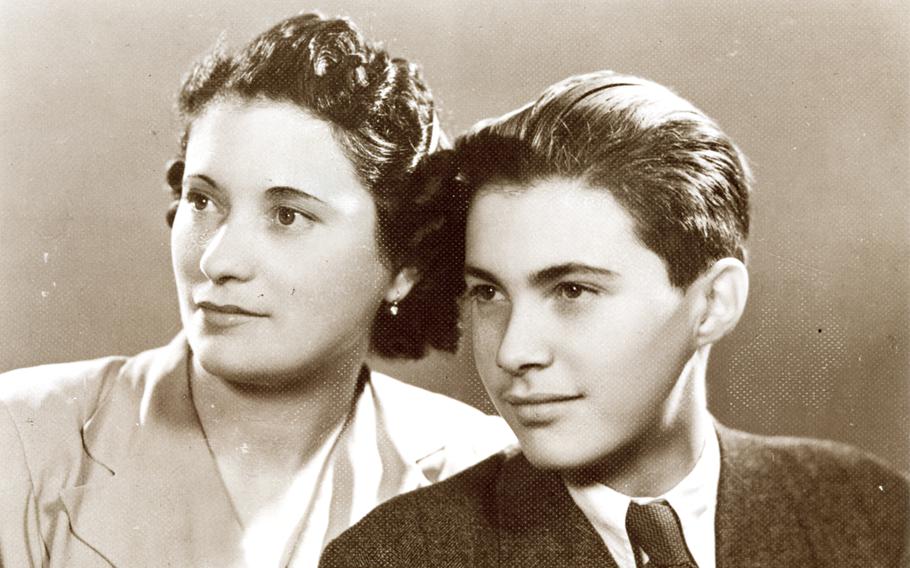

Holocaust survivor Erzsebet Barsony and her son, Ervin Fenyes, in 1943 in Budapest. (U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum/Centropa)

Erzsebet Barsony and her son, Ervin Fenyes, had been packed in a cattle car for three days en route to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in Poland. It was July 12, 1944, and very hot. They had no food or water, only their clothes.

The police had taken Erzsebet’s wedding ring and Ervin’s shoes back in Budapest, where they were rounded up. She was 35. He was 15. He stood over 6 feet tall and played the violin. She kept telling him to sit down in the jammed car so he would take up less room.

When they arrived, they were immediately separated, as were tens of thousands who went through the same ordeal. “I was standing there with my emotions numbed,” she recalled. Suddenly, Ervin appeared at her side. He had left his place to say goodbye. Tearfully, he hugged and kissed her, and told her not to worry. “Mom, you’ll see, we’ll meet again.”

They never did.

When she told this story in her apartment in Budapest about 60 years later, Erzsebet Barsony was a frail, white-haired woman of 96. Her interviewers said she spent most of her time in her rocking chair with her cat, Mici, in her lap, sitting beneath a photograph of Ervin in a black frame.

She died shortly afterward, in 2005. Now her account and thousands of other personal histories and photographs have been added to the collection of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, museum officials said.

A wedding picture of Erzsebet Barsony and her first husband, Mor Fenyes, taken in Budapest in 1928. (U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum/Centropa)

Late last year, the museum finalized the acquisition of the archive of Centropa, a nonprofit founded in Vienna and Budapest in 2000 to gather and preserve the life stories of elderly Jews, mostly in Central and Eastern Europe, the officials said.

The Centropa archive includes 25,000 digitized family photographs and documents, and 45,000 pages of interviews in 11 languages. More than 1,200 people were interviewed in 20 countries.

Not specifically a Holocaust project, the archive portrays local Jewish life before, during and after the World War II murder by Nazi Germany and its allies of about 6 million Jews.

“This brings to the fore voices, perspectives, experiences that are not always at the center of the discussion when it comes to Holocaust history,” Zachary Paul Levine, director of the Holocaust Museum’s Archival and Curatorial Affairs Division, said in a recent interview.

“It’s an incredible amount of information … a major addition to the museum’s collection of records of the Holocaust,” he said.

The museum declined to say what it paid for the archive, but Levine said the amount covered the value of the material and some of the work that went into gathering it.

He said the museum plans to have the archive available on its website this spring. It is also available on Centropa’s website.

That website gets about 250,000 visitors per year. The Holocaust museum’s website gets about 36 million.

Many of the Centropa stories, like most from the Holocaust, are heartbreaking. In addition to her son, Erzsebet Barsony lost her husband and her parents as well as her older brother, his wife and their 6-year-old son. She barely survived.

“I got home with nothing but the clothes on me,” she remembered. “Strangers lived in my house. … My only desire was to die.”

Katarina Lofflerova, who survived Auschwitz and also lost her husband and her parents, recalled encountering a former classmate in their hometown of Bratislava, then in Czechoslovakia, after the war.

Lofflerova, who was 94 when she was interviewed, remembered that her former classmate, as a Nazi operative helping to round up Jews, had pointed a machine gun at her and threatened to shoot when she asked for a drink of water for her ailing mother.

When she spotted him after the war, he tried to elude her. But she chased him down. He gave her a strange smile.

“You dirty, lowest of killers,” she said to him. “Villainous trash.”

Then she slapped him and knocked off his glasses, which broke when they hit the ground.

“He didn’t say a word, just stood there, like a petrified statue,” she said. But as she walked away, she began to cry. Even though she had seen awful things in the camps, she felt remorse that she had struck another living being, she said.

She recalled another incident after the war when she applied for permission to attend a funeral in Austria. A government official came to her home and reviewed a form she had filled out.

She had put marks beside the names of her parents. What were the marks for, the official asked. To point out that her parents had died in Auschwitz, she said.

“Anybody can say that,” he replied. “Maybe in the meantime, they’re living in America and things are going great there for them.”

She was furious. She stood up and said, “Get out!” Her parents were martyrs, she told him. “Get out!”

The official looked terrified. “He thought I might beat him up or I don’t know what,” she recalled. He hurried out of the apartment, leaving his hat. She picked it up and threw it after him.

Survivor Anna Lanota recalled being holed up in a house in Warsaw’s Old Town neighborhood, printing the Polish resistance newspaper on Aug. 26, 1944. The bloody Warsaw Uprising against Nazi Germany’s occupation was underway.

She was pregnant and was still recovering from a bullet wound in a foot, accidentally inflicted by a comrade. She carried a gun and had a fake ID. She was 29.

She had studied psychology in college and had worked with mentally disabled children. She read Adolf Hitler’s antisemitic manifesto, “Mein Kampf,” and couldn’t comprehend it. “We thought he was a bit crazy,” she recalled.

Her husband, Edward, a member of the resistance whom the Germans were after, was in another room. They had been married about two years. He called her Hania.

The Nazis, who had occupied Poland since 1939, had been pounding Old Town for days trying to crush the uprising.

“Right at the start … my husband said to me, ‘There won’t be victory here, only defeat,’ ” she told her interviewer in 2004 when she was almost 90. “But it didn’t occur to us not to fight. To fight the Germans was happiness.”

As she worked on the newspaper, a bomb with a time-delay fuse crashed into the house.

“Hania!” her husband called out.

“I’m here,” she said.

A comrade grabbed her and threw her through a hole in the wall out onto the street as the bomb exploded, killing him and her husband, and wounding her.

She was taken to a basement hospital and patched up. She and others in her group escaped through the sewers as rats skittered by and the Germans dropped grenades through the manholes.

Several months later, her daughter, Malgorzata, was born.

Centropa — the Central Europe Center for Research and Documentation — was established by Edward Serotta, 74, an American author, photographer and filmmaker now based in Vienna.

He had relocated from Atlanta to Budapest in his 30s to pursue journalism. He said he became fascinated by the stories told by elderly Jews, many of whom had lived through World War I, World War II, the Holocaust and communism.

He said he wound up spending more and more time on projects, interviewing survivors in their kitchens and living rooms, hearing stories and looking at yellowed photographs. He said he thought: “Who collects stuff like this?”

He decided he would. He assembled interviewers who helped identify candidates and then would visit them and record their oral histories. The recordings were transcribed, and old family photos were copied and digitized.

The project was funded by foundations and several European governments. It became a lifelong endeavor. But as time passed, he said, “I wanted to make sure, at my age, that there would be a permanent home, that this archive and stories would live in perpetuity.”

He had trouble getting other people interested, because the archive was unusual. “I went to one library and museum after another and just couldn’t find the interest,” he said.

Meanwhile, Levine started working at the Holocaust Museum in June 2020. He and Serotta had met when Levine was a graduate student living in Budapest. Levine had used the Centropa archive and did some editing for the project.

He heard that Serotta was trying to find a permanent home for the archive and that the museum was discussing it.

“Fairly quickly, the stars started to align, where we could have the conversation about adding this material to the collection,” Levine said.

Levine said his grandparents, who were Holocaust survivors from Poland, used to say: “There’s nothing back there. It’s all gone.”

“But these communities didn’t stop,” he said. “They put pieces together so they could have a life.”

Holocaust survivor Katarina Lofflerova in 1999 in Bratislava, Slovakia. (Edward Serotta)