A U.S. soldier stands by a UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter before taking off from Khost, Afghanistan, Aug. 14, 2002. For the first time, U.S. soldiers have begun aerial vehicle checks near the Pakistan border, an area where Taliban and al-Qaida members are believed to have been regrouping. (Scott Schonauer/Stars and Stripes)

This article first appeared in the Stars and Stripes Europe edition, Aug. 17, 2002. It is republished unedited in its original form.

KHOST, Afghanistan — The helicopters swooped down like two eagles cornering their prey.

One Army UH-60 Black Hawk landed in front of the sports-utility vehicle, while the other came down at the rear of it. As soon as the choppers touched the dirt road, two squads of heavily armed soldiers emerged.

“We’re doing this for your safety and ours,” a U.S. soldier said to the SUV through an interpreter. “We mean no harm.”

The teams looked for weapons, documents or any signs the men might be Taliban or al-Qaida fighters. In what seemed like a one-in-a-million chance, they also checked to see if the Pentagon’s two most wanted — Taliban leader Mullah Mohammad Omar or suspected terrorist mastermind Osama bin Laden — were inside.

Soldiers only found some papers they deemed “suspicious” and confiscated them for analysis. In 30 similar vehicle searches, they also came up empty.

But those who planned and executed the mission said the so-called “aerial vehicle checks” served as a warning to those who want to attack U.S. forces in Afghanistan or disrupt the interim government.

The surprise checks using Apache and Black Hawk helicopters are part of a new effort by American troops to prevent Taliban and al-Qaida from migrating between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

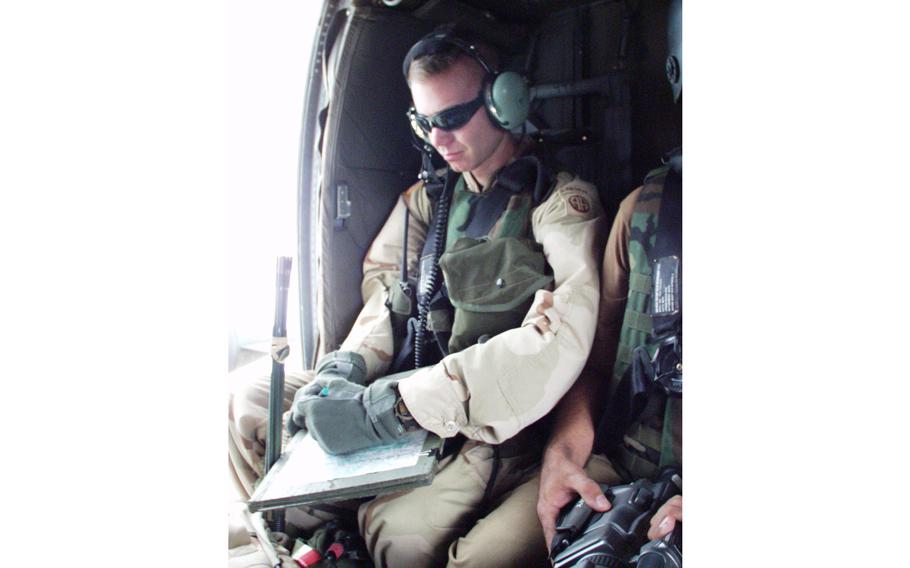

Master Sgt. Curtis Curry gets ready for an aerial vehicle check from inside a Black Hawk helicopter. (Scott Schonauer/Stars and Stripes)

There is speculation that the two groups have fled Afghanistan and are using Pakistan as a new staging area for fresh attacks.

Wednesday’s five-hour mission was a trial run of what could soon be routine, soldiers with the 82nd Airborne Division said.

If anything, Sgt. 1st Class Richard Lopez said the checks show that the coalition forces can go beyond the traditional stationary road checkpoints to help seal the border. They can now do it by air, very quickly.

“It’s faster, and it catches them by surprise,” said Lopez, a platoon sergeant with the 1st Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment. “It’s also an intimidating factor to have two helicopters come down on you out of nowhere.”

The sight of two helicopters with nearly a platoon of American soldiers must have startled most of the people stopped. But the soldiers got little resistance. Everyone cooperated, soldiers said.

“They didn’t have a problem at all [with the searches],” said 2nd Lt. Rob Swartwood, the platoon leader.

The checks — most of which were conducted in the region of Khost, near the Pakistan border — lasted only about 10 minutes each.

This is how it worked: Soldiers in one Black Hawk would slip in and out of the valleys looking for any vehicles on the move. Once a vehicle is spotted, the pilot in one of the helicopters would move the chopper closer, so the squad leader could get a better look inside.

If the platoon leader wants the vehicle searched, two Black Hawks block the vehicle from the front and back. As soldiers — along with an Afghan interpreter — pour out from the helicopters, an Apache helicopter lingers nearby for extra firepower and protection in case something goes wrong.

Once soldiers secure the area, a smaller group searches the vehicle.

Lt. Shawn Callahan uses a map to mark where Army soldiers stopped and searched vehicles near Khost, Afghanistan. For the first time, U.S. soldiers have begun aerial vehicle checks near the Pakistan border, an area where Taliban and al-Qaida members are believed to have been regrouping. (Scott Schonauer/Stars and Stripes)

Several of the checks on Wednesday attracted a crowd from the nearby villages and hamlets. As helicopters swarmed one vehicle, people came out on their rooftops to get a better view of the action.

The concern is that an attacker could hide in the crowd.

“It sends a good message to the local populace that we’re checking the vehicles,” Swartwood said of the onlookers. “But it makes things a little more tense.”

For most men in the platoon, it was their first mission outside the confines of Bagram air base, the main U.S. base in Afghanistan.

Using photographs, soldiers try to determine if any of the passengers are Taliban or al-Qaida leaders. But Swartwood said matching the people in the vehicles with the pictures of the leaders is difficult.

“To be honest, a lot of these guys look alike,” he said.

Most of the vehicles stopped contained farmers or businessmen, who were trucking goods from Pakistan to Afghanistan.

Soldiers, however, believe it is possible that in future missions they will find Taliban or al-Qaida supporters or soldiers. They said the checks will, at the very least, make it more difficult for such people to enter Afghanistan.

“There’s no way they can predict where we’re going to go next,” Swartwood said