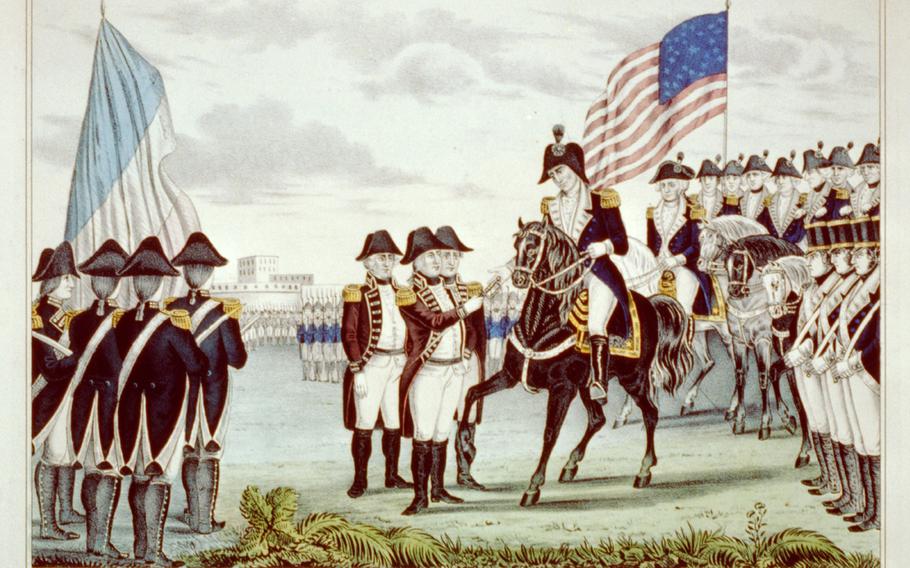

A print of the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown, Va., in 1781 shows Maj. Gen. Charles O’Hara, surrounded by French and American soldiers, handing over his sword. (Library of Congress)

The cannon fire from the besieged British was deadly. One shot had just killed four Americans. Another had killed a drummer who had stepped from cover. Yet, as the Americans dug their trenches closer and closer, one man stood in the open, taunting the enemy gunners.

Each time the British shot and missed he waved his spade in defiance, saying he’d be damned if he would duck. “Possessed of more bravery than prudence. … He had escaped longer than could have been expected,” Capt. James Duncan, an American officer, recorded in his diary.

But the unnamed soldier was foolish, Duncan wrote, and finally “a ball came and put an end to his capers.”

Last month, the diary was put up for auction at Sotheby’s in New York, where it was anticipated to bring between $300,000 and $500,000. But the bidding that day only reached $240,000, short of the expected minimum, and the diary was not sold.

But last week, a spokeswoman for Sotheby’s said the diary sold privately the day after the auction. She declined to identify the buyer or the exact price but said it was above $300,000.

“To have an English-language contemporary journal written by a Continental [Army] soldier … is exceptionally rare,” Selby Kiffer, Sotheby’s international senior specialist for books and manuscripts, said before the auction.

“The content, the fact that it was about such a pivotal event, that fact that it just reads wonderfully — this gripping, first-person narrative — that fact that it’s still in the family of Captain Duncan,” he said.

Most such accounts that have come to the market recently are in French. “Which is wonderful,” Kiffer said. “Obviously, our French allies played an enormous role, not only in Yorktown but in winning our independence.”

Duncan’s diary “is very much the narrative of a citizen soldier,” he said. “It shows us, I believe, that the Revolutionary War was won by people like Duncan and people like his comrades, the ones who were being killed or maimed by cannonball.”

Kiffer added: “It’s one thing to read a letter from Washington in which he’s discussing strategy. Here is war stripped down to its real horrors.”

The 23-page Yorktown account is contained in a 110-page notebook - about 8 inches by 6 inches - that includes other jottings unrelated to the war as well as some blank pages.

It’s a story of bloody trench warfare that sounds more like World War I than 1781, with soldiers hunkering in dugouts under enemy shellfire and charging across no man’s land.

On Oct. 14, as Duncan and two friends were sitting in a crowded trench around midnight, a sentry called out a warning of an incoming shell.

Duncan had jumped up to see where it was headed as it landed in the trench about two feet from him and blew up. “I immediately flung myself” aside, he wrote.

“Although the explosion was very sudden and the trench as full of men as it could possibly contain, yet not a single man was killed,” he wrote. “Only two of my own company [were] slightly wounded.”

He added: “We all counted it a most miraculous escape. Were I to recount all the narrow escapes I made that night it would almost be incredible.”

Duncan mentions several historic figures who fought in the siege and the war: the French officers Lafayette and Rochambeau, the Prussian Baron von Steuben and the impetuous 24-year-old Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton.

Duncan respected Hamilton as “one of the first officers in the … army” but criticized him for one reckless maneuver.

On Oct. 7, Duncan recounted, “We were ordered to mount the bank, front the enemy, and there by word of command go through all the ceremony of soldiery, ordering and grounding our arms.”

Although the British had been firing, “they did not now give us a single shot,” he wrote. “I suppose their astonishment at our conduct must have prevented them, for I can assign no other reason.”

Duncan wrote, “Colonel Hamilton gave these orders. Although I esteem him … I must beg leave in this instance to think he wantonly exposed the lives of his men.”

(The Broadway hit musical “Hamilton” includes a dramatic song about Yorktown.)

Duncan described events as the Americans and the French gradually closed in on the British, who were pinned against the York River in Yorktown, about 160 miles south of Washington.

On Oct. 11, he wrote:

“Last night commenced a very heavy cannonade and the enemy returned the fire with no less spirit. … The largest of the enemy’s vessels was set on fire by the bursting of a shell or red hot ball from some of our batteries, and communicated it to another, both of which were burnt down.

“They must have lost a considerable quantity of powder in the last, as there was an explosion which made a heavy report. The whole night was nothing but one continual roar of cannon, mixed with the bursting of shells and rumbling of houses torn to pieces.”

Duncan, who was about 25, was born in Philadelphia. He gave up his preparations for the ministry as the war broke out and volunteered to serve in George Washington’s Continental Army, Sotheby’s said.

At Yorktown, he became a member of Brig. Gen. Moses Hazen’s brigade. Duncan was well educated. He wrote legibly, using an ink bottle and a quill pen, said Kiffer, the Sotheby’s expert. “He writes very well and very vividly,” he said.

The siege of Yorktown occurred at the end of the Revolutionary War, which lasted from 1775 to 1783 and led to independence from Britain.

The siege culminated with the surrender on Oct. 19, 1781, of the 8,300-man British Army under Lt. Gen. Charles Cornwallis to a combined American and French force under George Washington.

“It was the pivotal event in American history,” Jerome A. Greene wrote in his 2005 book about the siege, “The Guns of Independence.”

“Its successful conclusion virtually assured [the creation] of American democratic institutions from which all subsequent events followed,” he wrote.

Duncan survived the war, Sotheby’s said. He became a court official in Adams County, Pa., and was later elected to the U.S. House of Representatives but resigned before the Seventeenth Congress assembled. He died in 1844.