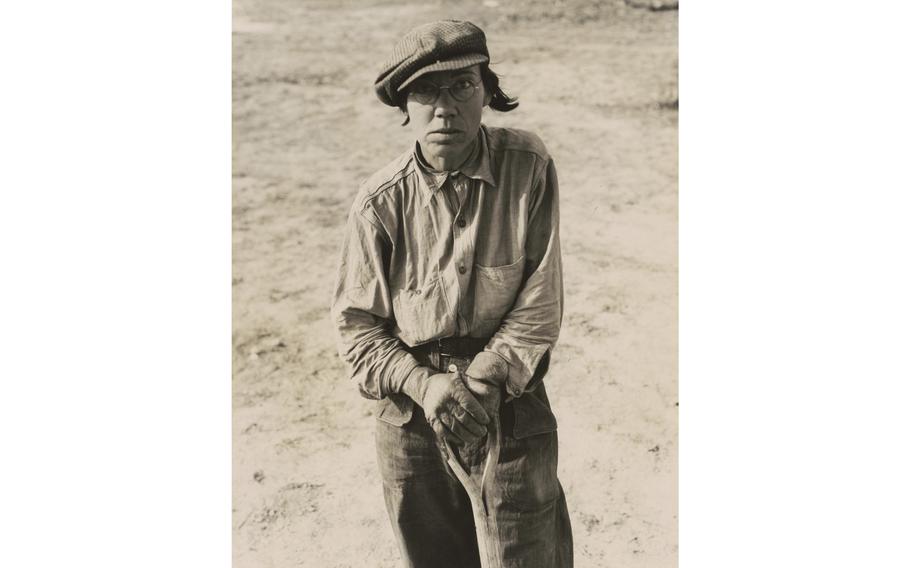

Dorothea Lange’s “Calipatria (vicinity), California. Native of Indiana in a migratory labor contractor’s camp. ‘It’s root hog or die for us folks.’,” February 1937, gelatin silver print. (National Gallery of Art/Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser)

Spend enough time on TikTok and you’re bound to find someone posting about the vibecession. Stories about price shocks in food or rent paint a grim picture of an economy that’s actually humming along. Some inflation-weary users go a lot further, posting misleading figures to make the case that the United States has plunged into a “silent Depression” to rival any downturn in American history.

Even a passing glance at documentary materials from the 1930s — the bread lines, the work camps, the images of chains of misery as migrants fled the Dust Bowl to find employment in the West — ought to throw cold water on this theory. One photographer, Dorothea Lange, was responsible for the gravest of those images, bridging the gap between individual experience and national story.

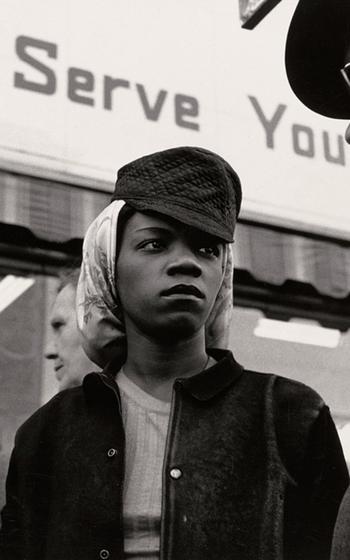

Dorothea Lange’s “Street Encounter, Richmond, California,” c. 1943, on view at the National Gallery of Art. (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art/Gift of Hallmark Cards)

Lange’s work includes some of the starkest photographs in American history, images that convey the toll of the Depression more clearly than any line chart. Alarmists who compare the present-day recovery with the Depression hope to lay claim to the level of despair that Lange’s portraits made so vivid.

Yet for all its moral authority, Lange’s work was also a vector for manipulation and propaganda. “Dorothea Lange: Seeing People,” an exhibit on view at the National Gallery of Art, shows how the artist explored portraiture and developed the nascent documentary form. A strong undercurrent in the survey teases out how Lange helped to establish and reinforce official narratives about Depression-era resilience and the wartime economy.

“Seeing People,” which was skillfully assembled by National Gallery curator Philip Brookman, proceeds chronologically through Lange’s life. It begins with her work as a portrait artist in the Bay Area, where she moved as a young adult from New York and fell in with a crowd of photographers that included Imogen Cunningham and Consuelo Kanaga. Brookman traces Lange’s interest in social justice through her pictures, including a gnarly portrait of seamen’s union leader Andrew Furuseth, his chiseled mug captured in profile. Lange had a novelist’s eye for detail: “Stenographer with Mended Stockings, San Francisco, California” (1934) focuses on the gothic textures of a woman’s threadbare stockings, omitting her face.

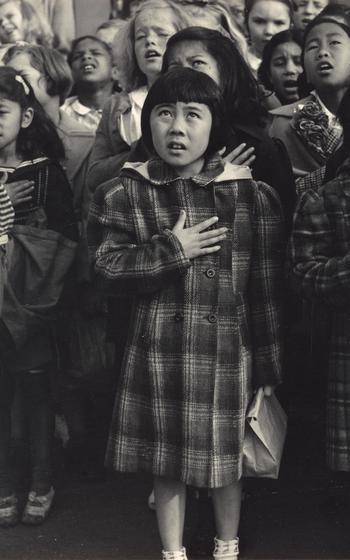

Dorothea Lange, “Children of the Weill Public School Shown in a Flag Pledge Ceremony, San Francisco, California,” April 1942, printed c. 1965, gelatin silver print. (National Gallery of Art/Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser)

People who never set foot in a museum will recognize “Human Erosion in California” (1936), one of the most powerful images of the last century. The photo captures a weathered woman staring into the distance as she clutches her three daughters, an embrace worthy of a Renaissance painting of Madonna with child. The fraying fabric of her blouse and wrinkled worry lines on her brow tell a haunting story of uncertainty. Known as “Migrant Mother” ever since its first publication, Lange’s photograph belongs to the rare category of portrait that helps people connect to art and history alike.

“Migrant Mother” is not a disinterested document, though, not in the way that viewers might understand a news image today. In 1935, Lange started working with the federal Resettlement Administration, later reorganized as the Farm Security Administration. “Migrant Mother” quickly emerged as a totem for the New Deal, evoking not just compassion for its unnamed subject but also support for the policies meant to alleviate her suffering. For a portrait artist, Lange yielded immense power, capturing the story of the Depression while also guiding the public’s perception of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s response.

Brookman’s presentation puts Lange’s deft touch front and center. A close-cropped image of a figure at a demonstration in 1934 frames a banner that reads “Feed us!” — a tight composition with all the compact charge of Eugène Delacroix’s revolutionary painting “Liberty Leading the People” (1830). In a wartime snapshot for Fortune, Lange seizes on a moment between a Black woman and a White man near the shipyards; behind the figures in “Street Encounter, Richmond, California” (1943), the artist frames a sign that says “Serve Yourself” — cut off at “Serve You.” Lange’s best-known photographs are poignant, but her work could also be tart.

While Lange was working in a mode between portraiture and photojournalism, she was always mindful of form. A dynamic crop of shadows cast by shipyard construction workers in “End of Shift, Richmond, California” (1942) helped to send the message that America was getting back to work. “Dispossessed Arkansas farmers. These people are resettling themselves on the dump outside of Bakersfield, California” (1935) shows evidence of “burning,” a darkroom technique to make part of an image darker (for the composition’s sake, in this case). Burning and “dodging” are still the names for the tools artists use to manipulate light and dark in Photoshop today.

Dorothea Lange’s “Man at Microphone, May Day Demonstration, San Francisco, California,” 1934, gelatin silver print. (National Gallery of Art/Gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser/The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor)

Brookman’s presentation puts Lange’s work in its appropriate political context. After FDR signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942, authorizing the removal of 120,000 Japanese Americans to incarceration camps, Lange was commissioned by the War Relocation Authority to document the process. The artist’s typically empathetic photographs — among them “Japanese American-Owned Grocery Store, Oakland, California” (1942) — were never shown during the war.

Lange herself suffered from certain forms of cultural myopia: “Hopi Man, Arizona” (1923) and other early photographs of unnamed subjects risk casting Native people as a type, not individuals. Florence Thompson, the woman pictured in “Migrant Mother,” was identified only decades later, after she complained about the image; the story of Thompson, born to Cherokee parents on Indian Territory and forced out of Oklahoma by state dispossessions of Native land, bore little resemblance to the suffering that Lange was commissioned to find.

The National Gallery is not above imposing its own political sensibility on Lange’s work. The museum changed several titles used by Lange in order to apply modern ideas about language. “Former Slave, Alabama” is shown as “Formerly Enslaved Woman, Alabama” (1938), for example. “Negro” was changed to “Black” throughout as well. These are small, justifiable edits that nevertheless illustrate how facts drift over time, distorted by consensus and, later, history. Then as now, the truth is a reflection of the edit.

If you go

Dorothea Lange: Seeing People

National Gallery of Art, West Building, Sixth Street and Constitution Avenue NW. nga.gov.

Dates: Through March 31.

Prices: Free.