A ghost forest of trees killed by salt water intrusion at the USS North Carolina Battleship National Historic Site. (Justin Cook/for The Washington Post)

WILMINGTON, N.C. — Another high tide, and retired Navy Capt. Terry Bragg wades from his office into a flooded parking lot in the rain boots he always keeps close at hand.

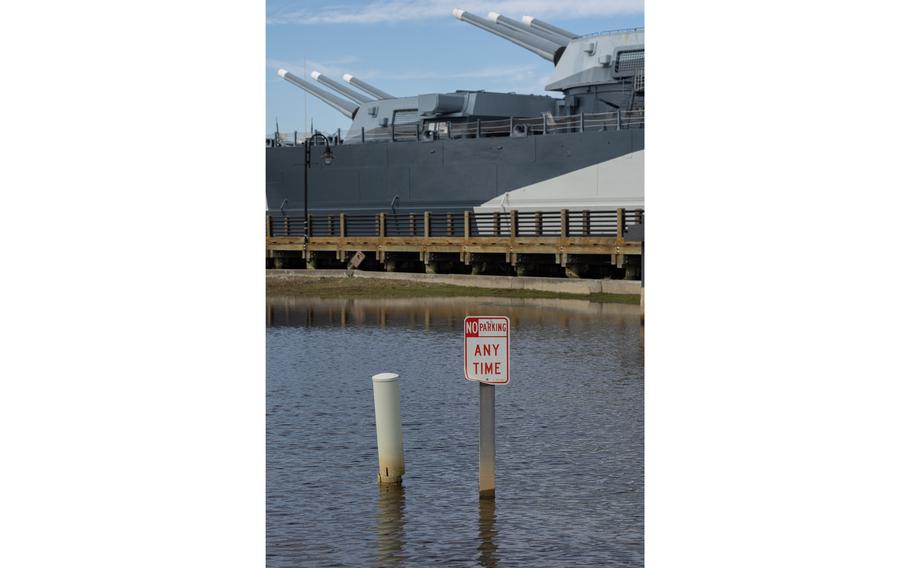

Around him, the water on this otherwise ordinary Tuesday creeps over concrete sea walls and fills drainage ditches. It covers swaths of grass and swallows most of a nearby fire hydrant. It devours stretches of sidewalk and inches past dead and dying oak trees hung with Spanish moss, their leafless limbs an unmistakable sign of their roots’ constant exposure to saltwater.

In barely half an hour, it is a foot deep or more in places. The water has consumed hundreds of parking spots and created an obstacle course for anyone trying to navigate to the visitor’s center of the historic Battleship North Carolina, which for more than six decades has been anchored here, across the Cape Fear River from downtown Wilmington.

“This is climate change,” Bragg, the site’s executive director since 2009, says as he stands ankle deep in floodwaters that inch higher by the minute.

The hulking battleship behind him is many things: a floating museum and one of North Carolina’s most visited tourist sites; the most decorated U.S. battleship of World War II, with 15 battle stars; and an enduring memorial to the more than 11,000 North Carolinians who served and died in that war.

But its site on low-lying Eagles Island also faces serious peril from rising seas and constant inundation.

Retired U.S. Navy Capt. Terry Bragg, the executive director of the Battleship North Carolina museum, poses for a portrait in a flooded parking lot at the historic site in November 2023. (Justin Cook/for The Washington Post)

The museum’s leaders have documented a more than 7,000 percent increase in tidal flooding at the site since it opened to the public in 1961. The changes in the past decade or so alone have been dramatic. In 2011, the battleship site recorded about 20 flood events. By 2020, the property was flooding roughly half of the year. The trend shows no signs of slowing.

In 2022, even though the museum had nearly a quarter-million visitors and its most successful financial year ever, the site experienced nearly 200 days of flooding. Officials had to close it at times when the lone access road vanished underwater or visitors couldn’t safely navigate the salty lake that forms in front of the main entrance to the 35,000-ton warship.

“If I can’t sell tickets and provide parking, I can’t keep the battleship open,” Bragg said of the site, which is overseen by a state commission but receives no regular government appropriations for its operations.

Without some sort of intervention, there’s little doubt that the problem will become more dire. The battleship sits 28 miles upstream from the Cape Fear River’s confluence with the Atlantic Ocean and about a half-mile from a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration tidal gauge that has been collecting water level data continuously since 1935.

In that time, its data shows, sea levels at that spot have risen roughly 9 inches, although the rate of rise has accelerated over the past decade. Scientists project that they could rise another foot by the middle of the century.

“You can see the change,” said Jenny Davis, a North Carolina-based research ecologist at the National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, which is part of NOAA. “The number of flood events is only going to increase over time.”

That is true for sites all on the East Coast, which face growing threats from sea-level rise and repeat flooding. But that’s where the Battleship North Carolina’s story diverges from that of some other spots confronting similar risks.

Looking down at the bow of Battleship North Carolina. (Justin Cook/for The Washington Post)

Feeling an urgency to act — and knowing that only worse problems could be on the way — the site’s leaders decided several years ago that they did not want to try to hold back the rising waters.

Instead, they would look for a way to live with the changing landscape around them, even if that meant doing what many places are not willing to do: surrender land back to nature.

Over time, Bragg said, he and his colleagues sought data and advice from coastal flooding experts, including at NOAA. Several years ago, they solicited proposals from four architectural and design firms about solutions to mitigate the incessant flooding at the battleship site.

“Three of the four said, ‘Let’s build walls around it,’ ” he recalled.

The engineering firm Moffatt & Nichol proposed a different path. In short, it boiled down to an idea that has long been embraced in places such as the Netherlands but only in more recent years has begun to take root and become more common in the United States: accommodating the rising sea rather than viewing it as an enemy to conquer.

“It’s the concept of being able to look at water as an asset,” said Dawn York, a senior coastal planner for Moffatt & Nichol who has spent years shaping what lies ahead for the Battleship North Carolina.

“It’s been proven over and over again that when you design a project with the natural system intact, then that project actually holds up better to storm events and requires less maintenance over time. It’s more sustainable.”

Dawn York, a senior coastal planner at the engineering firm Moffatt & Nichol, photographed in Wilmington, N.C., in November 2023. York is working on plans for elevating the Battleship North Carolina’s parking lot and re-naturalizing the flooded portion into a marsh with a tidal creek that will absorb typical tidal floodwaters. (Justin Cook/for The Washington Post)

The approach that has taken shape on Eagles Island has several central elements.

At one of the site’s lowest points, workers will remove approximately 800 feet of concrete barriers and other rocky armoring and create a “living shoreline” made up of earthen berms and native vegetation to help lessen wave and tidal erosion and create habitat for an array of wildlife, including shrimp and blue crabs.

There are plans to restore much of the flood-prone parking lot to a tidal creek and wetland similar to what would have been there generations ago. That will mean tearing out acres of pavement and other impervious surfaces and replacing them with a more natural landscape meant to capture, hold and ultimately direct tidal floodwaters back to the Cape Fear River.

Such a design also leaves open the option to expand and adapt the natural areas if sea levels continue to rise.

Meanwhile, the remainder of the battleship’s parking area will be raised above the current high-tide line, and plans call for a complex of “green” infrastructure features to help manage and filter storm water runoff.

The project includes the planting of roughly 100 trees and shrubs in the reworked parking lot area, as well as putting in more than 130,000 native marsh plants intended to support nesting and migratory birds.

A sign stands in floodwaters in the parking lot of the USS North Carolina National Historic Site. (Justin Cook/for The Washington Post)

“We’re going to improve water quality, improve drainage, improve safety,” said Chris Vargo, a retired U.S. Coast Guard lieutenant commander and the battleship’s assistant director, whose family once bought him a tide watch for Christmas so he could know how much flooding he might need to navigate on his way to his office each day.

Construction on the project is expected to begin as soon as this month and take roughly eight months. The goal is to wrap up ahead of the peak of the coming hurricane season, which runs from June through November.

The estimated $4.1 million cost of the initial work will be paid for in part with nearly $2 million from a collection of state and federal grants, more than $1 million in the recently approved state budget and funding from the North Carolina Department of Natural and Culture Resources.

“We planned to what our budget allowed,” Vargo said, adding that the environment around the ship changes so fast that “really none of us know how much water we’re going to be dealing with [in the future].”

Those who have helped to shape the “Living with Water” project say they are grateful that the leaders of the battleship site were willing to experiment to ease the chronic flooding.

“They are not fighting to hold the water back,” said Davis, the NOAA ecologist. “It’s not the approach that’s taken most of the time, so it’s novel in that aspect.”

York said that while the project is not massive in scale, it could demonstrate what is possible if other places facing similar problems are willing to adapt by returning certain spots to nature.

“They are willing to give up land they will never get back to return it to its natural use. They knew that was necessary,” she said. “The real risk is doing nothing.”

Miguel Mendoza and Iris Valerio take a selfie on the USS North Carolina in Wilmington on Nov. 28, 2023. (Justin Cook/for The Washington Post)

Bragg has high hopes that the nature-based overhaul will mean brighter — and drier — days for the Battleship North Carolina in the years to come. But given that seas keep rising and that scientists expect stronger storms and torrential rains to continue to batter the East Coast, he knows the work is unlikely to be a permanent fix.

“I think this project has a design horizon of 15 or 20 years as a solution,” Bragg said. “If the flooding and climate change continue to manifest as it has, we will continue to have a problem.”

That timeline sounds about right to York. The current project isn’t meant to prevent damage from major hurricanes or flooding from monumental deluges. But it should buy time from the ravages of the near-daily flooding that has plagued the historic spot in recent years.

“There are no guarantees,” she said. “There may need to be other adaptations to be able to sustain this site in the future, as we continue to see climate impacts increase. It’s going to be a really interesting case study of how these type of nature-based projects are sustained over time in these kind of environments.”

But York, who has lived in Wilmington for nearly three decades, also calls the effort “one of the most personally and career-gratifying projects I’ll probably ever have the opportunity to work on.”

If it succeeds, she says, the project will help to preserve and enhance part of the coastline she holds dear and also to safeguard a place that honors service members such as her late father, a Navy veteran, and her grandfather, who served in World War II.

“For me,” she said, “it’s a commitment to history and to the environment.”

Water from the Cape Fear River trickles into the parking lot at the USS North Carolina Battleship National Historic Site on Nov. 28, 2023. (Justin Cook/for The Washington Post)