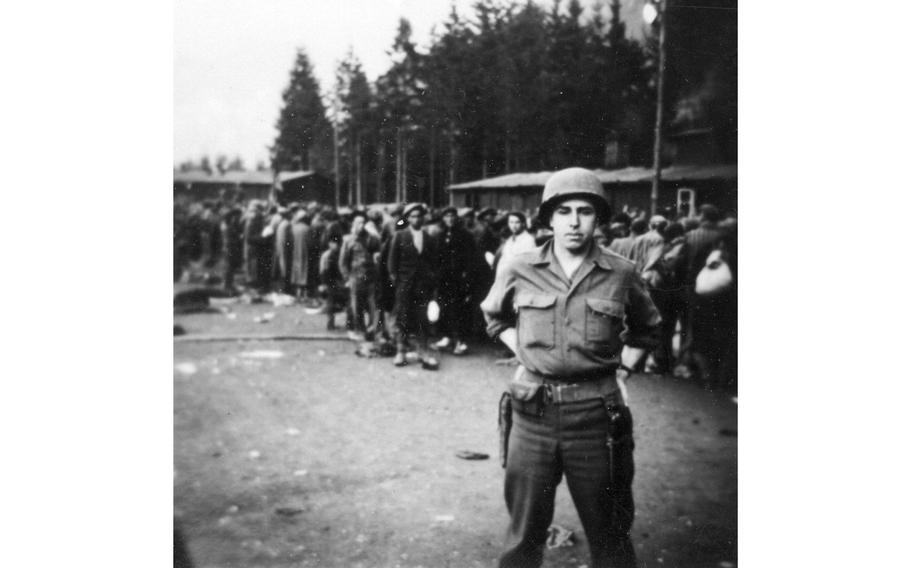

Elements of the 3rd Cavalry Group (Mechanized) liberated Ebensee concentration camp in Austria on May 6, 1945. (3d Cavalry Regiment/X)

GREENSBORO, N.C. (Tribune News Service) — An American soldier helping to liberate a concentration camp finds one of the prisoners collapsed in a ditch.

The man is suffering from typhoid fever.

The soldier knows he needs help and drives him to a hospital not far away.

The Hungarian teenager in the ditch was Zev Harel, who has spent the decades since looking for that man. He sees him as a hero of World War II. If only he could find him or his family so he could say that. And so much more.

Harel doesn’t know the soldier’s name.

Or rank.

Or hometown.

Or anything that might help identify him.

Just his unit — the Army’s 3rd Cavalry Group.

In 1945, the Allies freed prisoners of the notorious Auschwitz concentration camp and others. Harel, who spent time in Auschwitz, was by then in the brutal Ebensee work camp, which the 3rd Cavalry liberated.

The soldier he knows nothing about — other than he was Black and attached to the 3rd Cavalry — but not for a lack of trying.

Years later when Harel, by then with a degree from Hebrew University, came to the United States to continue his education, he landed in Ohio and reached out to then- U.S. Sen. John Glenn, the former astronaut and retired colonel, and U.S. House Rep. Lou Stokes, the longtime politician and civil rights attorney.

But they could not find anyone matching Harel’s tale.

Harel wasn’t content to stop there. If he couldn’t find the soldier, he would pay it forward, working on the needs for the African American community, especially seniors.

Days became months. Months became years. Years became decades.

Now 93 and in Greensboro, Harel hasn’t given up. He’s still telling his story — with the hope that it might get to the right ears. His recollections are among the oral histories on file at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

He does not know if the soldier is alive, although many Americans who fought during World War II were likely not much older than Harel was at the time.

Maybe there are friends and family of the soldier who have heard the story from his point of view.

Maybe someone reading this will be able to help.

“I owe my life to him,” Harel said.

Growing up in a small village back in Hungary, Harel was largely carefree, climbing trees and spending time with his grandfather, who was his hero. The family later moved to the city.

Harel remembers the changing attitudes toward him and other Jews in his native country. He was about 10 in 1940 when the Hungarians began treating Jews very much like the way Germans did. Jewish children were soon excluded from schools. His father couldn’t continue to work as an engineer.

“You were not allowed to walk the streets during certain hours,” Harel recalled.

Soon many were forced out of their homes and into ghettos. His family was among those crowded into an abandoned factory.

Then the cattle cars arrived in May 1944.

Jews were headed to concentration camps where some lost their lives almost right away in the gas chambers.

“I will forever remember that night,” Harel said. “The night was beautiful. The sky was full of stars. The stench was overwhelming.”

Those physically able were sent away to perform manual labor.

Harel was just 14 and warned to lie about his age. Younger prisoners were almost always taken to the gas chamber. Another prisoner who had been assigned tasks by a Nazi guard told him to say he was 17.

He experienced the brutality of the camps. Guards would use their rifle butts at will on prisoners. And they did other things. Unspeakable things.

“The Nazi guards were doing all kinds of evil at will,” Harel remembered. “It is hard for me to comprehend this level of brutality.”

He was there for a year working by day and suffering in silence at night.

By the time the Allies arrived in 1945 and the doors to the camps were swinging open, Harel and the others marched right out. But he wouldn’t get far.

“As I was walking out, I fell into a roadside ditch,” Harel recalled.

That’s when he felt the hands of the American soldier.

“Had he not stopped to pick me up,” Harel said, “I would not be here.”

The soldier drove him to a hospital in a nearby town 10 miles away in Linz, Austria.

“He asked the nurses to nurse me back to life,” Harel said.

Harel spent the next three weeks there.

But not once had he knowingly been in the company of the American soldier again.

After he left the hospital there was little time to squander. Harel went back home where he was reunited with is brother, who also survived the Nazi brutality, but they didn’t want to stay there. They moved to Israel and attended school.

Harel enrolled at Hebrew University, where after earning a degree, he received a scholarship to attend the University of Michigan to work on his master’s degree in social work. There he would meet his future wife, Bernice. He later earned a doctorate in social work at Washington University in St. Louis. He moved to Ohio and took a job at Cleveland State University.

That’s the story of what became of Harel after the war.

But what happened to the unknown soldier? What’s his story? Did he survive the war? Did he make it home?

The search over the years has been hard.

Glenn and Stokes, the politicians, had little to offer beyond what little information was already known.

“Between the two they had all kinds of connections but they couldn’t come up with records on the attached unit,” Harel said.

In Ohio, Harel and wife Bernice raised a family while at Cleveland State. He was there 40 years before retiring as professor emeritus and following his youngest daughter to Greensboro 11 years ago.

Harel, an American citizen, has stayed busy. He is a member of the North Carolina Council on the Holocaust, which has input into student textbooks. He has written extensively on the Holocaust.

In 1995, during celebrations for the 50th anniversary of the liberation, Harel did meet the commanding officer of the squadron that liberated his camp. But time, and the way African American soldiers were treated by the system, have worked against him.

Harel is hoping that as he spreads his story, it might reach someone who might have had a connection with the soldier.

“I’d just like to shake his hand.”

Nancy.McLaughlin@greensboro.com

(c)2023 the News & Record (Greensboro, N.C.)

Visit www.news-record.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.