President John F. Kennedy and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev watch as Khrushchev’s limousine pulls up following one of their meetings at the U.S. Embassy in Vienna, Austria, in June 1961. At right, Secretary of State Dean Rusk confers with his Soviet counterpart Andrei Gromyko. (Gus Schuettler/Stars and Stripes)

Friday, Nov. 22, 1963, began like any other day for Walter Cronkite, the anchor of “CBS Evening News.” He got to the CBS newsroom in Manhattan around 10 a.m., his usual start time, and spent the morning at his desk poring over the newswires, looking for stories to cover in his evening broadcast. President John F. Kennedy was touring Texas and would give a speech that afternoon in Dallas. That would surely be worth a mention.

Then, around 1:30 p.m., a wire came in that changed everything. Cronkite’s editor, Ed Bliss, went to retrieve it. He said, “They say shots rang out in Dallas as the president’s motorcade was going through the city.”

“Oh, my God! Stay on it,” Cronkite responded. He got up from his desk to see the wire himself. By then, another had come in: Kennedy was hit. He was being driven to a hospital.

Cronkite went on the air right away. About an hour later, it fell on him to break the news to America that Kennedy was dead. With a grave look on his face, he announced: “From Dallas, Texas, the flash apparently official: President Kennedy died at 1 p.m. Central Standard Time.”

The news traveled around the globe. Whatever else was happening in the world that day grew irrelevant. The attention of humanity was focused on Kennedy’s assassination.

“The reaction globally was one of shock and incredulity,” said Fredrik Logevall, a Harvard professor and the author of the biography “JFK: Coming of Age in the American Century, 1917-1956,” as well as a forthcoming second volume. “People struggled to comprehend that the American president, who seemed to be in the prime of his life and who was such a global icon, was dead. ‘Can it really be that he’s gone?’ That was a universal question people asked themselves.”

In New York City, traffic screeched to a halt. “Is it true?” people shouted in desperation. In the city’s hospitals, some patients flipped out upon hearing the news. Doctors had to inject them with tranquilizers.

Not far away, on Long Island, the artist Elaine de Kooning was in her workshop. She happened to be painting a portrait of Kennedy, according to Thurston Clarke in “JFK’s Last Hundred Days.” The president had commissioned the portrait a year earlier. “The assassin dropped my brush,” she later said.

In Chicago, at a swanky restaurant, patrons left in the middle of their meals. Rather than wait for their checks, they dumped cash on the tables. Elsewhere in Chicago, a man walking on a street wondered why everyone was acting so strangely. He spotted a stranger holding a transistor radio against his ear and inquired, “What’s the news?” “He’s dead,” responded the stranger. Then the stranger grabbed him by the collar and said, “Pray, man.”

On the campus of the University of Delaware, a junior was leaving class. The hallways were buzzing. He ran to his car and turned on the radio. He was devastated. “How is that possible in the United States of America?” he thought. He had always felt a special connection to Kennedy: Like the president, he hailed from an Irish Catholic family. Joe Biden had just turned 21.

In Washington, the Soviet ambassador, Anatoly Dobrynin, was in the middle of a dentist appointment. The radio was playing music in the background. Suddenly, the music stopped and Dobrynin heard Kennedy’s name. But he couldn’t understand what was being said. “The president has been assassinated,” the dentist clarified, before instructing a stunned Dobrynin to keep his mouth open so he could continue working on his teeth.

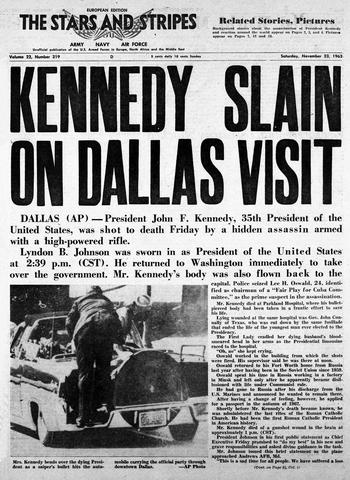

The front page of the European edition the day after president John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas in 1963. (Stars and Stripes)

In Atlanta, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was at home, glued to the TV. His wife, Coretta, was with him. After Kennedy was pronounced dead, King turned to Coretta and said, “This is what is going to happen to me. This is such a sick society.”

Across the Atlantic Ocean, night had fallen. In London, at the Old Vic Theatre, the actor Laurence Olivier was performing. But, as William Manchester recounts in “The Death of a President,” Olivier stopped acting after learning the news and instructed the public to rise to their feet as the orchestra played “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

In Rome, in homage to “il presidente,” cabbies parked a white taxi adorned with a black wreath in front of the U.S. Embassy, a palazzo on the posh Via Veneto. A 20-minute drive away, in Vatican City, the pope prayed in his private chapel.

In West Berlin, under heavy rain, 60,000 people carrying torches gathered in silence outside City Hall. It was past midnight. “We feel like our father has been taken from us,” a young German mechanic mourner told the AP. “We feel left alone.”

In Paris, hundreds of people came together on the Champs-Élysées. President Charles de Gaulle was astonished that the French would mourn a foreigner — a Yankee to boot. “I am stunned,” the proud Gaul admitted. “They are crying all over France. It is as if he were a Frenchman, a member of their own family.”

In what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in the province of Katanga, ministers paid their respects at the U.S. Consulate. “We Bantus always mourn the passing of a great chief,” they said.

In Japan, in the village of Shiokawa, villagers woke the mayor, Kohei Hanami, in the middle of the night to tell him about Kennedy’s death.

Hanami had a history with the president: He had almost killed Kennedy in wartime. During World War II, he had captained a Japanese destroyer. And in 1943, in the South Pacific, Hanami’s destroyer had sunk a U.S. torpedo boat, PT 109, commanded by Lt. John F. Kennedy. Kennedy had been heroic and saved most of his men.

Hanami had a soldier’s respect for him. “The world has lost an irreplaceable man,” he said.

It wasn’t just Kennedy’s former foes mourning his passing; his current Cold War antagonists felt sorrow too. “Even behind the Iron Curtain, there were genuine expressions of grief at the news that JFK had died,” said Logevall.

In Moscow, it was almost 11 p.m. when Radio Moscow interrupted a classical concerto and broke the news. A New York Times reporter in the Soviet capital was struck by the “genuine grief of the Muscovites.”

At a bus stop on Gorki Street, half-an-hour from the Kremlin, people were in shock. “He was a good man,” a woman said. “It is always the good who suffer.” A man responded, “It is bad for the American people and for our people.”

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev was in his house in Kyiv when the phone rang. His foreign minister told him about Kennedy. Khrushchev wept. “The fact that the leader of the other superpower, supposedly an arch-foe, had this kind of reaction is extraordinary,” said Logevall.

Only a year earlier, Kennedy and Khrushchev had squared off during the Cuban missile crisis. Nuclear war had been narrowly averted; diplomacy had triumphed. Since then, the two leaders had fostered détente between the United States and the Soviet Union.

In August 1963, they had signed a treaty banning most nuclear tests. More was in the offing. In September, Kennedy had proposed a joint American-Soviet mission to the moon. He had even begun to secretly plan a trip to Moscow to see Khrushchev in 1964, probably after the presidential election in November, which he was favored to win.

In his speeches, Kennedy spoke of world peace as achievable and hailed “a new approach to the Cold War — a desire not to bury one’s adversary, but to compete in a host of peaceful arenas, in ideas, in production, and ultimately in service to all mankind.”

“The efforts that Kennedy and Khrushchev had made to lower the temperature of the Cold War had had real effects, and had changed the tenor of superpower relations,” said Logevall. “The change to the geopolitical picture in the last year of Kennedy’s life contributed to the sense that we’d lost something here that was immense.”

Even Cuban leader Fidel Castro felt this sense of loss. He was lunching with Jean Daniel, an influential French journalist, on Varadero Beach, east of Havana. Daniel was there as Kennedy’s “unofficial envoy.” The president had met him a month prior and tasked him with sounding out Castro about the possibility of improving relations between the United States and Cuba.

But they had no time. Midway through lunch, a secretary barged in. There had been an assassination attempt on Kennedy. Castro told Daniel, “This is bad news.” He was so dismayed he repeated it twice more. He hoped Kennedy would pull through.

Moments later, he learned Kennedy hadn’t. Castro stood up. At 6’1’‘, with broad shoulders, he cut a towering figure. “Everything is changed,” he said. “Everything is going to change. ... The Cold War, relations with Russia, Latin America, Cuba.”

In Israel, it was early evening. David Ben-Gurion, the former prime minister, was listening to the radio when he heard the news. “It was one of the greatest shocks of my life,” he said in 1965. Then Ben-Gurion summed up why Kennedy’s sudden death brought humanity together in grief: “Such a promising young president. Really, he represented for the whole world their leader.”