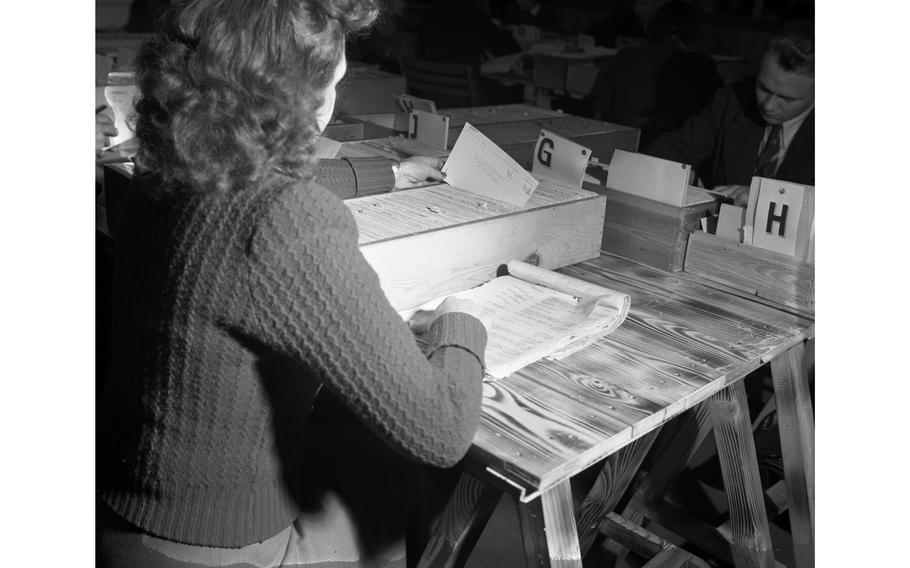

The card index of the International Tracing Service sometimes reveals the location of a lost child. (John W. Boyd/Stars and Stripes)

This article first appeared in the Stars and Stripes Europe edition, Feature Section, Jan. 15, 1950. It is republished unedited in its original form. The images seen here are a combination of two photo assignments and include images taken at the International Tracing Service’s then-offices in Esslingen, Baden-Wuerttemberg, in 1950 to accompany this article, as well as images taken there in 1952 for an article on the search efforts of the organization published that year.

The greatest treasure hunt Europe has ever known has been going on since V-E Day.

Fifty investigators attached to the Child Search Branch of the International Tracing Service (ITS) are seeking out non-German children separated from their families during the war.

Nobody knows how many were separated from their parents, but estimates run into the hundreds of thousands.

A large proportion of the youngsters were taken by the Nazis from occupied countries — particularly Eastern nations.

They were victims of a ruthless kidnap scheme designed by SS chief Heinrich Himmler and his associates. Himmler’s twofold objective was to destroy potential leadership in the occupied countries and at the same time through “Germanization” of selected alien children provide an infusion of new blood for a war-depleted Germany.

The kidnaped waifs were to be trained as faithful Nazis, effacing any trace of their previous nationality, homelife, or parents, which might enable them to return.

Children with “aryan features” — blue eyes, blond; hair, whose head circumference and nose shape passed rigid examination by Nazi racial teams — were sent to the Lebensborn (Fountain of Life) agency, the National Socialist Welfare Organization (NSVD) and other similar Nazi organizations, which provided children with German names, birth certificates, and farmed them out for “Germanization” to foster homes and institutions. Children who were found ‘‘racially undesirable” were exterminated.

Thousands of other missing children came to Germany in a variety of ways.

Some accompanied their parents, brought into Germany as slave laborers. Others were part of the mass of refugees forcibly evacuated by the Germans as Allied armies surged on Germany. Some were born to non-German mothers working on German farms or industries.

Often, the records German organizations kept of the children were destroyed or deliberately falsified. In the majority of cases, more than six years has elapsed since separation, further obscuring any clues.

Such are the complexities of the task confronting Child Search investigators. Also hampering the search is not ever knowing how many children are to be sought.

An estimated 30,000 to 40,000 children were repatriated in early postwar years by Allied armies and a search group of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA).

ITS and the Child Search were organized later as a branch of the International Refugee Organization (IRO).

ITS is grappling with its monumental task of identifying and tracing children in a number of ways.

Its investigators made an exhaustive search of adoption records and orphanage rosters in Germany, and have scanned every Lebensborn list discovered.

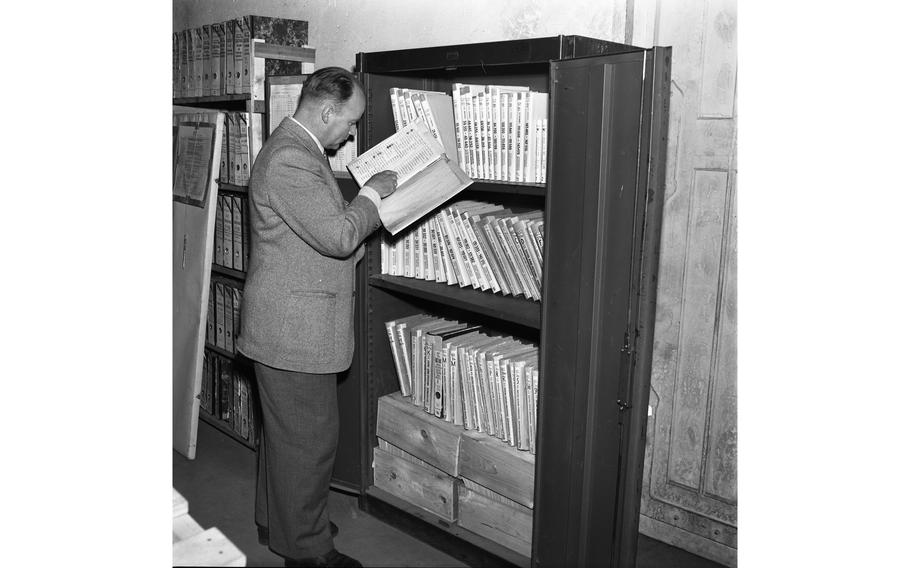

Undamaged records of concentration camps, some meticulously preserved by German officials, have been forwarded to ITS officials by Allied authorities. Field searches by ITS investigators have unearthed clues.

No matter how meager a lead, investigators painstakingly have run it down. Just how remote some of the clues have been and ITS’ persistence in following them through is illustrated by the following case.

The child, later identified as Peter K., was born in Germany in March 1945, and was picked up after an air raid. There were no papers to identify the baby and the mother was presumably killed in the raid. The only clue to the child’s identification was a tablecloth in which the infant was wrapped and which belonged to a hospital.

Investigation disclosed that the tablecloth had been given to one Helena K., who arrived at the hospital a few days before with a child two or three days old. A man, named Josef K., brought Helena to the hospital. He said they were both Polish.

The child was registered with UNRRA in February 1947 as a result of a quadripartite Allied directive on registration of all children believed to be non-German.

Child Search team investigators soon got the case. By exhaustive research, involving letters to England, questioning of German nurses, a court decision eliminating purposely false leads — it was finally established that Peter K. was Polish.

The case has been referred to the Polish Red Cross which is attempting to local relatives of the child.

Investigators, in tracing clues, have been balked both by the reluctance of a child to speak his native tongue, or “Germanization” that dimmed memories of parents and home.

Often, German foster parents, some who really love the foster children, some who fear being classified as Nazis, or some fearing to lose foster children exploited as a source of cheap household or farm labor, hold back vital information.

To winnow out facts and track down clues, an investigator must combine qualities as linguist, child psychologist, and detective.

Often, when speaking German to a child, investigators casually drop a question in Polish, French or Czech. The child replies in the same tongue sometimes, providing the first clue that may lead eventually to a reunion with family members. Sometimes remembrance has been rekindled by a snatch of a folk song or a native lullaby.

Operations for this vast tracing project are directed from offices located in a woolen factory in Esslingen, Wurttemberg-Baden. Here an international staff of about 250, directed by Child Search Branch Chief Herbert H. Meyer, sift and reconstruct clues, most gathered by their own effort.

Up to November 1949, Child Search has located 22,000 children. Another 3,000 have been located in response to queries. Children of 30 nationalities have been involved.

But in the three-month period ending last September, Child Search made its greatest strides, locating more children than in the preceding six months.

Child Search officials anticipate that this pace will be maintained and even stepped up in the future, as they have begun to exploit material submitted by German authorities. This material is exploited simultaneously by Child Search officials of IRO and the Child Search Bureau of the German Red Cross, thus at the same time solving cases of German children separated from their parents and other relatives during the war.

An investigator searches through the entry registers of the Dachau concentration camp in the records room of the International Tracing Service. (George Penn/Stars and Stripes)

This search, concentrating on boys and girls under 17, is being conducted among those now in foster homes, in institutions, and those who have been adopted by German families since Sept. 1, 1939. Names submitted by German authorities are checked against a Child Search master index of 204,000 cards, including 70,750 birth certificates.

Child Search will screen only those cases which are non-German, turning over others to German authorities, whose stake in the operation will be clues to displaced German children.

The job of Child Search ends when a missing child is located and proper authorities are notified. ITS is not involved in the future of the located child. This comes under the Child Care Branch of IRO, which works in close cooperation with the land commissioners’ offices in this matter.

One outstanding case, illustrating this, involved a Polish girl, Natalcia, who, at the age of 8 in 1941, was removed from Poland. ITS has on file copies of the letters Natalcia wrote her mother in the first days of separation.

In 1947, Child, Search investigators discovered Natalcia, then under her “Germanized” name of Friedl, living with German foster parents. Natalcia’s mother was notified and immediately wrote her daughter, asking her to return.

But after six years in a German home, Natalcia could no longer read her mother’s Polish script.

She wrote she was happier with her German foster parents, and cited her material gains and comforts over her life in Poland as she remembered it. In two years of pleading, Natalcia’s mother has not yet persuaded her 16-year-old daughter to forsake her foster home.

The International Tracing Service morphed into the Arolsen Archives and its staff continues the work their 1950s colleagues began. “The Arolsen Archives are committed to preserving their unique collection of documents on Nazi persecution and to making them accessible worldwide. We search for the traces of victims and survivors of the National Socialist terror regime and, even today, we are still helping to reunite families torn apart by the Holocaust, the persecution of minorities and forced labor.”

For more information about the organization, its archives and work, visit its website.