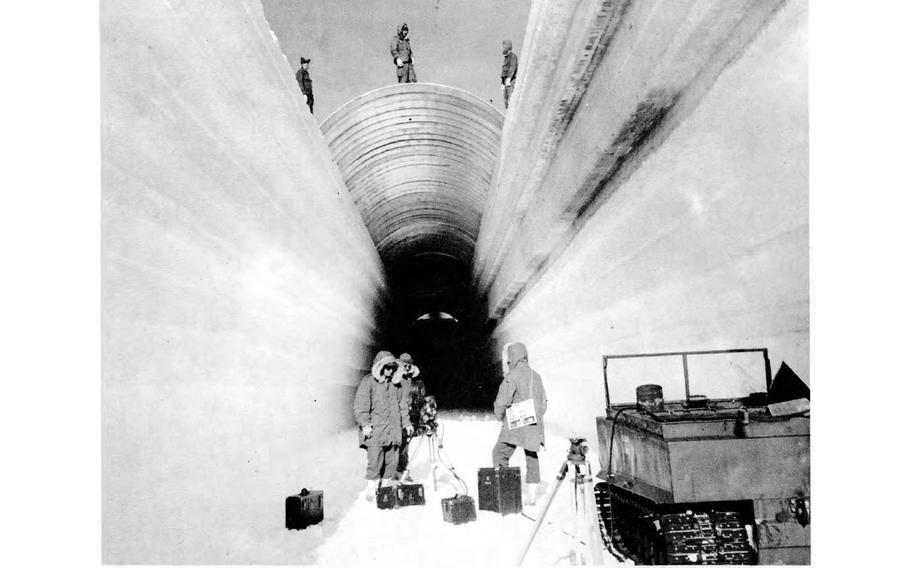

Camp Century trench construction in 1960. Camp Century was established in 1958, approximately 150 miles east of Thule, and was presented to the Danes as a scientific research site and a test area for construction work in arctic conditions. In reality, Camp Century was a major military installation, with almost two miles of covered trenches as well as laboratories, an underground railway track and a PM-2A portable nuclear reactor to supply power. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory)

In the late 1950s, the U.S. Army was under attack from a formidable foe: budgeting.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s “New Look” strategy sought to reorganize Cold War military funding so that it focused on tactical nuclear weapons as America’s main deterrent against potential attacks from the Eastern bloc. Defense spending would now be split among the Air Force (49%), the Navy (29%) and the Army, which was allocated the smallest share (22%).

Determined to preserve its status, the Army focused on promoting the ground deployment of mobile missiles as a key part of America’s nuclear deterrent. What the Army brass needed was a terrain that was within striking distance of the Soviet border and that offered a degree of natural concealment.

They found it in the frozen wilds of Greenland, which became the setting for Project Iceworm, a top-secret plan to convert part of the Arctic into a launchpad for nuclear missiles — and at the same time construct “a city under the ice.”

The goal of Project Iceworm, described by Professor Nikolaj Petersen of Denmark’s Aarhus University in 2007 in the Scandinavian Journal of History, seemed straightforward. Rather than base long-range Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) at silos in the United States where the Soviet Union might target them, the Army could instead burrow beneath a less monitored location, closer to the U.S.S.R.

The Greenland ice sheet lies less than 3,000 miles from Moscow. The plan called for digging underground trenches, through which medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBMs) could be deployed.

But before the requisite number of warheads could be installed, Project Iceworm came up against a force even greater than the Soviet Union or budget constraints: Mother Nature.

Long before a study last week found that a warming planet had claimed all but five of northern Greenland’s ice shelves and threatened a dangerous sea level rise, Greenland’s shifting ice compromised one of the U.S. military’s most audacious projects.

The plan to station nuclear missiles under Greenland’s ice was inspired by Bernt Balchen, a Norwegian-born U.S. Army colonel who in the 1930s had spearheaded polar aviation and who had pointed out the strategic advantage of Greenland’s location between the superpowers.

Balchen had been involved in the construction of two U.S. air bases in Greenland. He noted that the United States was permitted to store nukes in Greenland under the Thulesag 1 agreement, signed with Denmark in 1941 following the country’s occupation by the Nazis, which gave America jurisdiction over the defense of Greenland. (Greenland had been under Danish control since the 1814 Treaty of Kiel, and there were fears that the Germans might use Greenland as a base from which to attack North America.)

Despite the threat’s dissolution at the end of World War II, Soviet ICBM tests conducted in the 1950s and the launch of the Russian Sputnik satellite in 1957 reaffirmed the belief that a U.S. military presence on Greenland should be maintained. But how could America install underground nuclear missiles without transparently violating Denmark’s 1957 nuclear-free policy?

The solution was the construction of a polar training facility that would double as a cover story for digging into the ice. Camp Century was established in 1958, approximately 150 miles east of Thule, and was presented to the Danes as a scientific research site and a test area for construction work in arctic conditions.

The PM-2A portable nuclear reactor at Camp Century. (U.S. Army)

In reality, Camp Century was a major military installation, with almost two miles of covered trenches as well as laboratories, an underground railway track and a PM-2A portable nuclear reactor to supply power. But it served as only a microcosm of what Iceworm was intended to be.

The so-called underground city was planned to eventually be three times the size of Denmark, at 52,000 square miles, and include more than 2,000 firing positions through which the 600 MRBMs (nicknamed “Iceman missiles”) could be moved on rail cars. Eleven thousand service personnel would live under the ice and be rotated out of their posts via aircraft equipped with landing skis that would touch down on surface airstrips.

To keep those prospective personnel motivated, Camp Century would offer greater amenities than just the standard military running track and rec center. The base would feature a hospital, school and movie theater, and it was scheduled to receive two more nuclear generators to supply the installation’s energy once it had been fully constructed.

Snowplows designed in Switzerland began to dig trenches into the ice. The longest of these, at more than 1,000 feet, was nicknamed “Main Street.” Covered with steel arches and a layer of camouflaging snow, it was sturdy enough to house the convoy of Iceman missiles that would be transported under the ground, each of which would carry a warhead with a 2.4-megaton yield (150 times as powerful as the bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945).

If launched, 600 of these missiles would be sufficient to destroy 80 percent of U.S. targets in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. By contrast, the U.S.S.R. would need to launch an estimated 3,500 eight-megaton missiles to destroy the missile installation in Greenland — if it even knew of the facility’s existence beneath the ice.

It was the behavior of the ice that proved to be the program’s undoing (alongside its estimated $2.37 billion price tag, equivalent to $25.24 billion today). The slow but gradual winter movement of the Greenland ice sheet caused the trenches to warp, with the ceiling of the nuclear reactor room dropping by five feet in 1962.

Despite an attempt to raise it during that summer, the military — now aware of how tenuous an atomic city hemmed in by shifting ice seemed — took the cautious approach of downgrading Century to a summer camp in 1964, before finally abandoning the site in 1967.

Instead of launching missiles, the last noteworthy exercise performed at the base was the drilling of a probe a mile down into the underlying bedrock, which at least lent the “scientific test area” cover story fed to Denmark a note of truth.

Ironically, it was this drilling that gave Iceworm its greatest success. While the bedrock core extracted in 1966 was stored and ultimately forgotten, its rediscovery in 2017 revealed it to contain fossilized leaf and twig fragments, proving that plants had once grown under one of the coldest regions on earth.

This helped thaw some of the frostiness that had developed between the United States and Denmark when Project Iceworm was publicly disclosed in 1997. Similar tensions had struck decades earlier, when, during a routine surveillance flight south of Thule Air Base in 1968, a B-52 bomber crashed and spread its payload — four 1.1-megaton thermonuclear bombs — over sea ice in North Star Bay. Air Force personnel and the local Inuit population were requested to assist with the cleanup, which became informally known as “Dr. Freezelove” and recovered only three of the four ruptured warheads.

A missing atomic bomb isn’t the only U.S. military debris left in Greenland. When Project Iceworm was abandoned, it was hoped that the shifting ice that had compromised its construction would entomb the materiel the U.S. Army Corps of Engineer had left behind. This included 9,200 tons of building equipment, 53,000 gallons of diesel fuel, carcinogenic chemicals used in paint, and radioactive cooling water from the camp’s portable nuclear reactor.

A 2016 study suggested that these contaminants are likely to be released in a few decades’ time as a warmer climate continues to melt the ice sheet. This news seemed to confirm a Greenlandic proverb: “If you hush up a ghost, it grows bigger.”