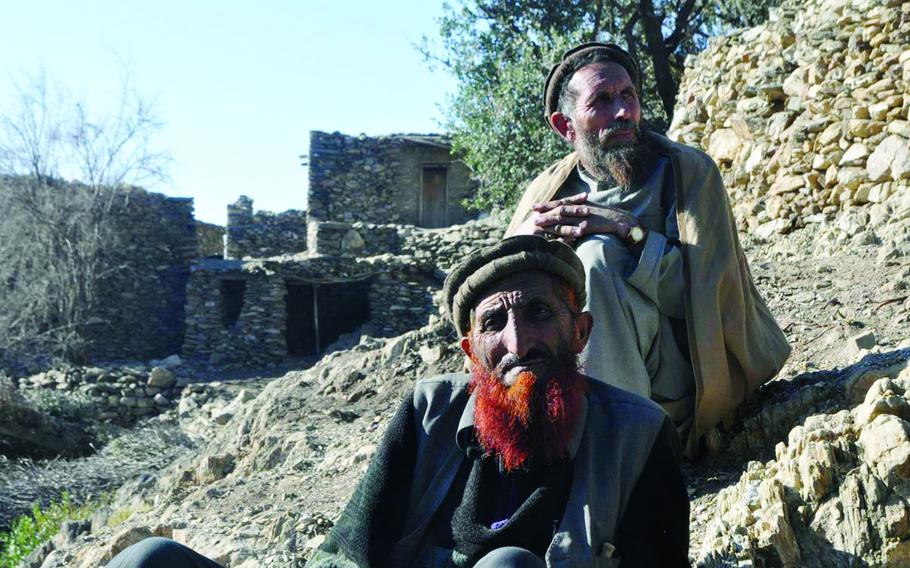

An estimated 50 to 75 people live in Barbar, a village in eastern Afghanistan’s Kunar province where U.S. and Afghan troops conducted a search mission in 2011. But when they arrived, the soldiers found only a handful of men and children in the village. (Martin Kuz/Stars and Stripes)

This article first appeared in the Stars and Stripes Mideast edition, Feb. 21, 2012. It is republished unedited in its original form.

BARBAR, Afghanistan — It’s said that war is 99 percent boredom and 1 percent sheer terror, so it follows that war coverage tends to dwell on the 1 percent.

But unlike reporters and readers, soldiers can’t ignore the 99 percent. They have to live the tedium.

Killing time

A U.S. platoon and two dozen Afghan soldiers gathered at 11 p.m. beside the stone-strewn landing zone at Combat Outpost Fortress. Their ride, a pair of Chinooks, would not arrive for more than three hours.

The temperature had dropped below freezing, and an occasional ripple of wind gave the winter chill a deeper bite. The American soldiers huddled beneath blankets, the shivering embodiment of the military’s unofficial motto: Hurry up and wait.

“All you can do,” said Sgt. Joshua Roque, 24, of Lawrenceville, Ga., “is try to stay warm until the birds come.”

The men with Company C of the 2nd Battalion, 35th Infantry Regiment were headed on a mission to search the village of Barbar, a suspected Taliban enclave in eastern Afghanistan’s Kunar province. By the time the operation ended the following night, the motto would need a familiar addendum: Hurry up and wait — then walk a long way for nothing.

Slow and steady

The rotor wash of the Chinooks provided welcome gusts of warm air as the U.S. and Afghan soldiers climbed aboard. Ten minutes later, they stepped onto a plateau a mile above sea level in the Hindu Kush mountains.

It was past 3 a.m. and a halfmoon cast the landscape in silvery shadows. The men started walking in a twisting line, taking small steps over loose rocks and around spiny brush.

Almost no one spoke. What little sound they made — the soft scrape of boots across dirt, the muted clatter of weapons and gear — was absorbed by the darkness.

The only noise to rise above the hush was a dull thud, punctuated by a grunted oath. Someone had fallen. He stood up, and the line regained its slow momentum.

The soldiers secured an overwatch point near Barbar as pink morning sunshine seeped over the mountain walls. The light revealed Roque’s improvised loincloth, a beige T-shirt that hung down from his belt to cover a rip in his pants.

“Bushes got me,” he said.

A pair of goats look on as U.S. and Afghan soldiers conducting a search mission move through the village of Barbar, a suspected Taliban enclave in eastern Afghanistan's Kunar province. (Martin Kuz/Stars and Stripes)

Goats, not glory

The ridge-line perch offered the soldiers a view of the Dewagal Valley and the mud-brick homes of Barbar a half-mile below.

Intelligence reports suggested that a midlevel Taliban operative lived in the village and insurgents stashed weapons and ammunition there as they moved to and from Pakistan, some 20 miles to the east.

The Afghan soldiers loped down into the valley to search dwellings and question villagers. Half the U.S. platoon followed around 8 a.m., after the Afghans radioed that they had completed the clearing mission.

The Americans found the village deserted except for a half-dozen men, a handful of kids and many, many goats.

The 50 to 75 people who live in Barbar had chosen a good day for a group outing.

Capt. Brad Wilson, the platoon leader, talked to a man whose face was as lined as the dry, broken earth.

“Are there Taliban here?” asked Wilson, 26, of Grand Rapids, Mich. “Do Taliban ever come through here?”

“No. No Taliban,” the man said through an interpreter.

“Yeah, no Taliban,” Wilson said in the drained voice of the unconvinced.

No Taliban, and the village sweep had turned up only a rusty box of machine-gun rounds and two mortar shells.

The soldiers had hiked miles for a paltry haul. Now they had to hike some more.

Time to wait

The Afghan soldiers wore no body armor and carried only weapons and ammunition. On the steep climb back to the overwatch point, they surged ahead of the Americans, who each humped 50 to 100 pounds of armor, gear, water, a weapon and ammo.

“I sort of hate to see them getting so far ahead of us,” Wilson said, looking up the trail at the Afghans. He and his soldiers had sat down to catch their breath.

Someone mentioned the lighter load of the Afghans.

“Yeah, I know, but still,” Wilson said.

Another soldier rolled his eyes. Wilson didn’t notice.

The Americans reached the top by early afternoon and rested under a golden sun. About two hours had passed when staccato gunfire broke the stillness.

The platoon quickly realized the shots were aimed at a small group of U.S. soldiers who had remained by the plateau where the helicopters would return that night. Wilson’s men watched, listened, held their fire. Waiting.

Near dusk, with the horizon tinting purple, the U.S. and Afghan troops trudged to the landing zone. They stepped onto the plateau close to 5 p.m.

The Chinooks would not arrive for at least four hours.